- History & Evolution

- Biosynthesis & dietary uptake

- Fructose and the microbiome

- Fructose and cardiometabolism

- Fructose and neurology

- Fructose and oncology

- Fructose and 5P medicine

- References

History & Evolution

1847: isolation | 1880s: stereochemistry | 1956: clinics | 1970s: industry | 2004: health concerns

Fructose entered the world of chemistry in 1847, when Augustin Pierre Dubrunfaut isolated it from sucrose (Rödel 1974). For decades it was also called levulose because its solution rotates plane polarized light to the left. In the 1880s-1890s, Emil Fischer revolutionized carbohydrate science by mapping relationships among glucose, fructose, and mannose and introducing Fischer projections, which fixed the stereochemical language we still use (Horton 2013). A clinical turn came in 1956-1963, when physicians characterized hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI), a recessive disorder of aldolase B, and explained the syndrome’s biochemistry (Chambers et al. 1956). The role of fructose in the food industry became prominent in the early 1970s after work on glucose isomerase brought about commercial high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) (Horton 2013). In 2004, after decades of increasing intake of HFCS sweetened beverages, their link with U.S. obesity trends was brought to light (Bray et al. 2004), catalyzing an enduring debate about the ethics of adding fructose and other sweeteners to our foods.

When it does make it into our plates and glasses, fructose has advantageous properties compared to glucose: it is generally ~1.2 to 1.7 times sweeter than sucrose (Fontvieille et al. 1989), thus requiring less fructose for the same sensation. However, this advantage is most pronounced in cold matrices. Classic psychophysical work shows fructose’s relative sweetness climbs at low temperatures and drops when heated (Green et al. 2015). The mechanistic study of the fate of fructose in the body further added fuel to the polemic, with the discovery that fructose is a substrate for hepatic lipogenesis.

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

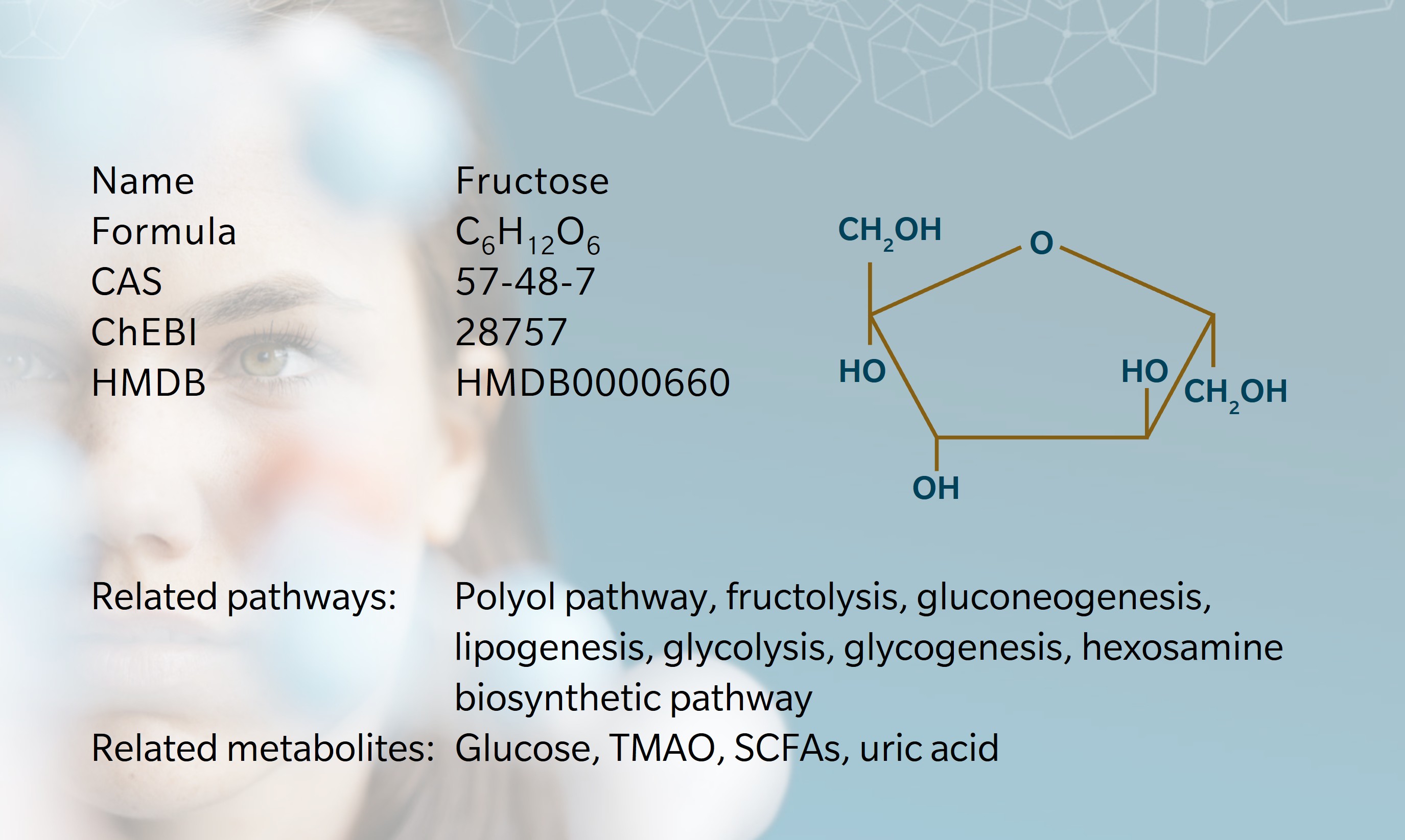

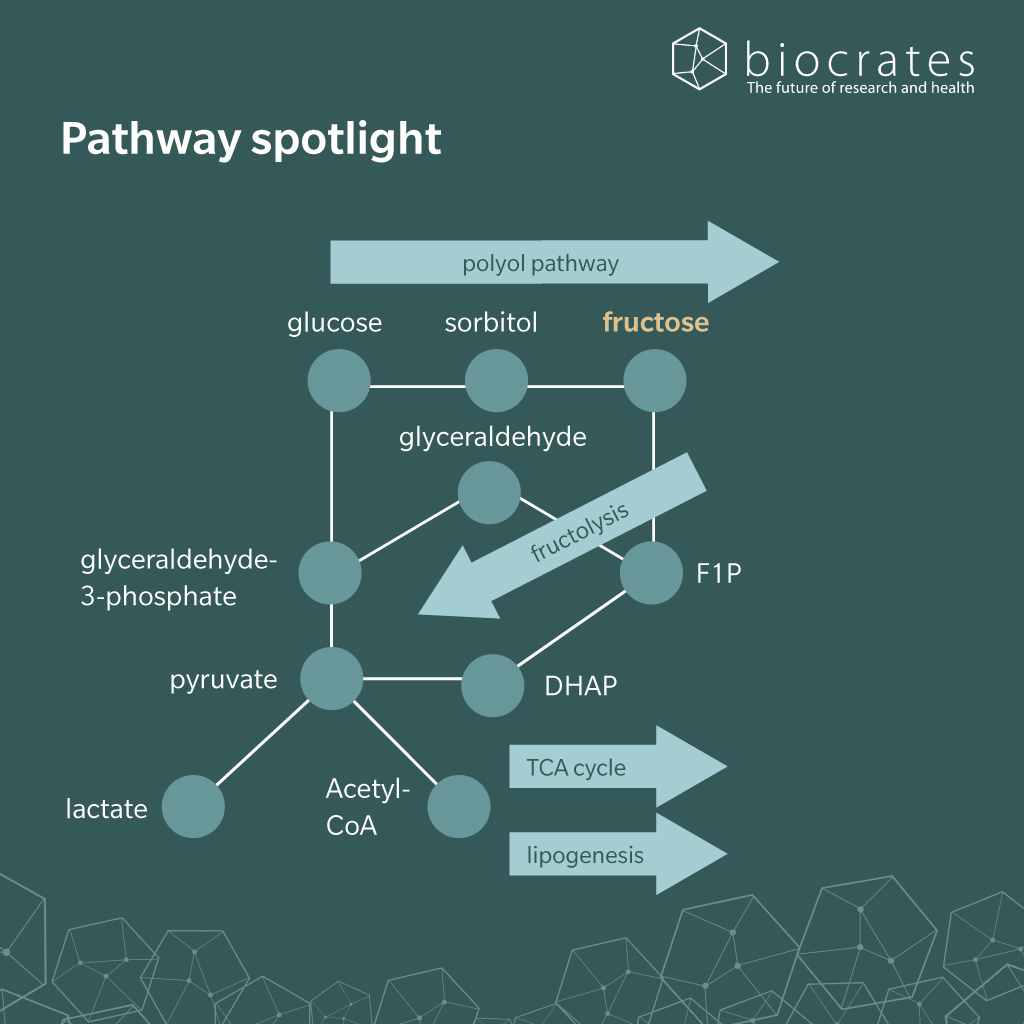

Fructose is a naturally occurring monosaccharide that can be produced endogenously in humans via the polyol pathway, where glucose is converted to sorbitol and then to fructose (Delannoy et al. 2025). In diet, fructose is abundant in fruits, honey, and some vegetables and is specifically present in processed foods as part of sucrose or in the form of HFCS (Flores Monar et al. 2025).

After ingestion, fructose is absorbed in the small intestine primarily via facilitated diffusion through the GLUT5 transporter located on the apical membrane of enterocytes (Taylor et al. 2021). Once inside the enterocyte, fructose is transported across the basolateral membrane into the portal circulation by GLUT2 (Jung et al. 2022). From the portal vein, fructose is delivered mainly to the liver, which serves as the central site of fructose metabolism.

Within the liver, fructose undergoes rapid phosphorylation by ketohexokinase (KHK) to form fructose-1-phosphate (F1P) (Flores Monar et al. 2025; Jung et al. 2022). Consequently, fructose-1-phosphate is cleaved by aldolase B into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde, intermediates which enter glycolysis or gluconeogenesis. A substantial fraction of these metabolites is directed toward de novo lipogenesis, contributing to triglyceride synthesis. A low flux of intermediates is directed towards the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, supporting the formation of sugar nucleotides required for proper protein glycosylation. This essential regulatory process controls protein folding, receptor signaling and immune function (Paneque et al. 2023).

Unlike glucose, fructose metabolism does not stimulate insulin secretion or leptin production, which has implications for energy homeostasis and lipid accumulation (Taylor et al. 2021; Flores Monar et al. 2025). Under normal physiological conditions, almost all absorbed fructose is processed during first-pass metabolism, so urinary excretion is negligible (Macdonald et al. 1978; Jung et al. 2022). However, in cases of fructose malabsorption or hereditary fructose intolerance, unmetabolized fructose may appear in urine and cause gastrointestinal symptoms (Simões et al. 2025; Febbraio et al. 2021).

Fructose and the microbiome

When the small intestine’s first-pass capacity to absorb fructose is exceeded, particularly with high loads of free fructose from HFCS-sweetened foods and beverages, unabsorbed fructose reaches the distal gut and becomes directly available to the microbiota (Jung et al. 2022; Febbraio et al. 2021). Chronic high free-fructose intake shifts microbial communities toward simple-sugar-degrading bacteria and away from key fiber-degrading taxa (Simões et al. 2025). By contrast, fructose in whole fruits is delivered within a fiber-rich matrix that slows its arrival in the distal gut and supports saccharolytic commensal bacteria (Simões et al. 2025; Febbraio et al. 2021). Microbial fermentation of unabsorbed fructose generates gases typical of malabsorption and produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Febbraio et al. 2021; Simões et al. 2025). Among SCFAs, acetate is particularly relevant because it enters the portal circulation and serves as a substrate for hepatic acetyl-CoA, thereby fueling de novo lipogenesis and linking microbial activity to liver fat accumulation.

In contrast, butyrate generally exerts anti-inflammatory and barrier-supporting effects in the colon. High-fructose diets also shift microbial metabolism toward cardiometabolic risk-associated metabolites such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) in mice (Jung et al. 2022).

In the same luminal environment, unabsorbed fructose can non-enzymatically be combined to dietary peptides and incretins through fructosylation. These fructose-derived advanced glycation end products (FruAGE) activate receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and amplify inflammatory signaling locally and systemically (DeChristopher 2024). As dysbiosis progresses, SCFA imbalance and microbial activity reduce gut barrier integrity, leading to a “leaky gut” with increased permeability. Translocated lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other microbial components then reach the liver, activate toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 on Kupffer cells, trigger tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)-driven inflammatory cascades, and propagate hepatic injury and metabolic dysfunction (Febbraio et al. 2021; Simões et al. 2025). Together, these processes link chronic high fructose exposure, microbial dysbiosis, impaired barrier function, and immune activation to a broad spectrum of metabolic and inflammatory diseases across the gut-organ axis.

Fructose and cardiometabolism

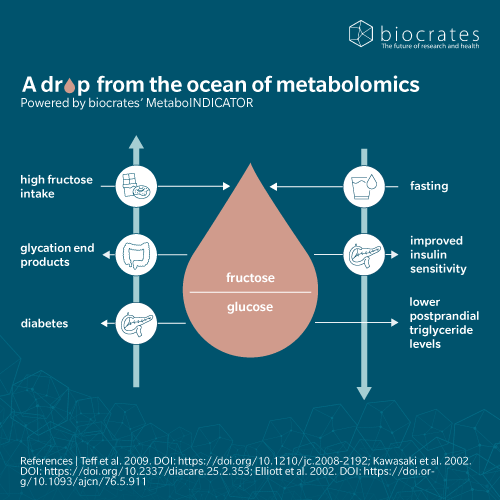

Over the past four decades, HFCS in processed foods and beverages has markedly increased dietary fructose exposure beyond normal physiological handling. This change parallels rising rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and cardiovascular disease, implicating industrial sweeteners as important contributors to cardiometabolic risk (Febbraio et al. 2021; DeChristopher 2024; Jung et al. 2022). Unlike fructose in whole fruits and honey, HFCS provides large amounts of free fructose in liquid form, bypassing the fiber matrix that normally slows absorption (Flores Monar et al. 2025; Jung et al. 2022). When intake is high, small-intestinal first-pass clearance saturates and excess fructose reaches the liver in substantial amounts (Jung et al. 2022; Febbraio et al. 2021).

In the liver, KHK-driven fructose phosphorylation bypasses phosphofructokinase and rapidly generates fructose-1-phosphate. This unregulated flux promotes lipogenesis while depleting adenosine-triphosphate (ATP) and trapping inorganic phosphate, activating adenosine-monophosphate (AMP) deaminase (AMPD) and increasing uric acid production. Elevated uric acid together with reactive oxygen species has been shown to promote endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and a pro-steatotic, pro-inflammatory hepatic milieu in animal models (Febbraio et al. 2021; Jung et al. 2022; Flores Monar et al. 2025). At the same time, fructose weakly stimulates insulin and satiety hormones such as glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1, lessening satiation and fostering increased energy intake and positive energy balance (Flores Monar et al. 2025).

These mechanisms collectively drive hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, core features of metabolic syndrome (DeChristopher 2024; Febbraio et al. 2021). Epidemiological data further link chronic high-fructose intake to hypertension, hyperuricemia and elevated cardiovascular risk independently of body mass index (Febbraio et al. 2021; Jung et al. 2022; DeChristopher 2024). Although the relative contribution of HFCS versus sucrose remains debated (Feinman et al. 2013) decades of excessive fructose consumption, particularly from sugar-sweetened beverages, represent a key factor in the growing burden of cardiometabolic disease (DeChristopher 2024; Flores Monar et al. 2025; Jung et al. 2022).

Fructose and neurology

In the hypothalamus of mice, chronic fructose exposure alters energy sensing and shifts neuropeptide signaling toward orexigenic, or appetite-stimulating pathways, thus directly linking high-fructose intake to positive energy balance and the metabolic changes in humans described above (Payant et al. 2021). The developing brain is especially vulnerable: in mice, early-life high-fructose diets impair microglial phagocytic activity, and reduce clearance of synapses and apoptotic neurons disrupts circuit refinement, leading to lasting deficits in learning and emotional regulation (Zelenka 2025). In the mature rodent brain, the hippocampus emerges as a key target of fructose-induced injury, with early mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and impaired neuronal insulin signaling. Some changes persist after dietary normalization and result in long-term memory impairment (Flores Monar et al. 2025; DeChristopher 2024).

Within this framework, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been hypothesized to be driven, at least in part, by overactivation of cerebral fructose metabolism, largely through endogenous fructose production via the polyol pathway. In neuronal models, fructose metabolism via KHK C causes energy depletion and uric acid generation, leading to mitochondrial oxidative stress, impaired mitophagy, reduced oxidative phosphorylation, cerebral glucose hypometabolism, and insulin resistance. Chronic energy failure promotes uric acid-driven neuroinflammation via NF-κB and TLR4 in rodents and humans (Shao et al. 2016). Disruption of plasticity-related pathways causes synaptic dysfunction in rodents. Amyloid/tau pathology might come secondary to oxidative stress and impaired protein repair also in humans. These processes might ultimately lead to neuronal dysfunction (Johnson et al. 2020).

High sugar and high-fructose intake, high glycemic load, excess salt, alcohol, obesity, diabetes, aging, and traumatic brain injury may all enhance endogenous fructose production by inducing aldose reductase and fructokinase in the brain. Consistently, the levels of sorbitol and fructose, as well as the activity of AMPD2 and production of ammonia are all increased in the brains of patients with AD. In both animal and human studies, high sugar intake was linked to cognitive decline, hippocampal inflammation, and reduced brain volume (Johnson et al. 2020; Flores Monar et al. 2025).

Fructose and oncology

High fructose intake has been associated with an increased risk of several cancers, with particularly strong epidemiological links to pancreatic cancer. Many tumor types overexpress the fructose transporter GLUT5, and elevated GLUT5 together with KHK expression indicates active fructose utilization by cancer cells (Jung et al. 2022; Febbraio et al. 2021). At the level of host tissues and the tumor microenvironment, fructose acts prominently along the gut-liver axis. Mouse models revealed that dietary fructose enhances epithelial cell survival and drives villus elongation in the intestine. The expanded absorptive surface area leads to increasing nutrient uptake and adiposity in the context of a Western diet (Taylor et al. 2021; Febbraio et al. 2021).

In the liver, fructose-induced fibrosis and inflammation promote an immunosuppressive milieu that weakens CD8⁺ T cell-mediated immunosurveillance and favors hepatocellular carcinoma development (Febbraio et al. 2021).

Fructose can also drive tumor growth through cell non-autonomous fructolysis in animal models: KHK-C-expressing hepatocytes convert fructose into circulating lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) that are taken up by cancer cells to support phosphatidylcholine synthesis and membrane biogenesis, with fructose supplementation enhancing tumor growth even without overt weight gain or insulin resistance (Fowle-Grider et al. 2024). In parallel, many cancers undergo intrinsic metabolic reprogramming to exploit fructose. Under glucose-poor, fructose-rich conditions, cancer cells can use fructose as an alternative carbon source to sustain central carbon metabolism, de novo lipid and nucleic acid synthesis, and the Warburg effect, with aberrant fructose utilization activating oncogenic mechanistic target of rapamycin complex (mTORC) 1 signaling and suppressing anti-tumor immunity (Ting 2024; Zhao et al. 2025). Different tumors deploy these pathways in distinct ways, for example, pancreatic cancer channels fructose primarily into nucleotide synthesis via the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, whereas hepatocellular carcinoma may rely on acetate derived from microbial fructose metabolism. Inhibition of fructose metabolism in such fructose-adapted cancer cells reduces malignancy (Ting 2024).

Fructose and 5P medicine

High intake of HFCS over long periods is a major, yet modifiable, risk factor for metabolic, neurological, and oncological conditions (Febbraio et al. 2021; Jung et al. 2022; DeChristopher 2024). Because diet is a central driver, fructose is an instructive example of how individuals can participate in shaping their health. Fructose from whole fruits, delivered with fiber and antioxidants, shows neutral or beneficial effects on metabolic biomarkers, whereas fructose from sugar-sweetened beverages and juices correlates with higher inflammatory markers, dyslipidemia, and intrahepatic fat (DeChristopher 2024; Jung et al. 2022). Experimental data indicate that HFCS-like, fructose-rich sweeteners induce reward-related and metabolic disturbances at lower exposure than sucrose, suggesting stronger reinforcing and pathological effects when fructose/glucose ratios are very high (DeChristopher 2024; Levy et al. 2015). Nonetheless, the most robust strategy for obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome remains a general reduction of total carbohydrate intake, not merely swapping fructose for glucose (Feinman et al. 2013).

When symptoms are present precision medicine gains importance. In inflammatory bowel disease and fructose malabsorption, several strategies improve gastrointestinal symptoms and breath hydrogen in clinical studies. These include fructose-restricted and low-FODMAP diets, microbiota-directed therapies (probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation), and oral xylose isomerase, which converts fructose to glucose (Simões et al. 2025). Regarding the gut-liver axis, KHK inhibitors, which are tested in clinical trials, lower de novo lipogenesis and improve metabolic markers (Jung et al. 2022). Epidemiological data also suggests that targeting brain KHK C or AMPD2, together with uric acid-lowering strategies, could enable to reduce the risk of dementia in the population (Johnson et al. 2020).

References

Bray, G.A. et al.: Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity (2004) The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.4.537.

Chambers, R.A. et al.: Idiosyncrasy to fructose (1956) Lancet (London, England) | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(56)92196-1.

DeChristopher, L.R.: 40 years of adding more fructose to high fructose corn syrup than is safe, through the lens of malabsorption and altered gut health-gateways to chronic disease (2024) Nutrition Journal | https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-024-00919-3.

Delannoy, P. et al.: Aldose reductase, fructose and fat production in the liver (2025) Biochemical Journal | https://doi.org/10.1042/BCJ20240748.

Febbraio, M.A. et al.: “Sweet death”: Fructose as a metabolic toxin that targets the gut-liver axis (2021) Cell Metabolism | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2021.09.004.

Feinman, R.D. et al.: Fructose in perspective (2013) Nutrition & Metabolism | https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-10-45.

Flores Monar, G.V. et al.: Mindful Eating: A Deep Insight Into Fructose Metabolism and Its Effects on Appetite Regulation and Brain Function (2025) Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism | https://doi.org/10.1155/jnme/5571686.

Fontvieille, A.M. et al.: Relative sweetness of fructose compared with sucrose in healthy and diabetic subjects (1989) Diabetes care | https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.12.7.481.

Fowle-Grider, R. et al.: Dietary fructose enhances tumour growth indirectly via interorgan lipid transfer (2024) Nature | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08258-3.

Green, B.G. et al.: Temperature Affects Human Sweet Taste via At Least Two Mechanisms (2015) Chemical senses | https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjv021.

Horton, D.: Carbohydrate Nomenclature | https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16712-6_67.

Johnson, R.J. et al.: Cerebral Fructose Metabolism as a Potential Mechanism Driving Alzheimer’s Disease (2020) Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2020.560865.

Jung, S. et al.: Dietary Fructose and Fructose-Induced Pathologies (2022) Annual Review of Nutrition | https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-062220-025831.

Levy, A. et al.: Fructose:glucose ratios–a study of sugar self-administration and associated neural and physiological responses in the rat (2015) Nutrients | https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7053869.

Macdonald, I. et al.: Some effects, in man, of varying the load of glucose, sucrose, fructose, or sorbitol on various metabolites in blood (1978) The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/31.8.1305.

Paneque, A. et al.: The Hexosamine Biosynthesis Pathway: Regulation and Function (2023) Genes | https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14040933.

Payant, M.A. et al.: Neural mechanisms underlying the role of fructose in overfeeding (2021) Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.06.034.

Rödel, W.: J. S. Fruton: Molecules and Life – Historical Essays on the Interplay of Chemistry and Biology. 579 Seiten. Wiley‐Interscience, New York, London, Sydney, Toronto 1972. Preis: 8,95 £ (1974) Food / Nahrung | https://doi.org/10.1002/food.19740180423.

Shao, X. et al.: Uric Acid Induces Cognitive Dysfunction through Hippocampal Inflammation in Rodents and Humans (2016) The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience | https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1480-16.2016.

Simões, C.D. et al.: Fructose Malabsorption, Gut Microbiota and Clinical Consequences: A Narrative Review of the Current Evidence (2025) Life | https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111720.

Taylor, S.R. et al.: Dietary fructose improves intestinal cell survival and nutrient absorption (2021) Nature | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03827-2.

Ting, K.K.Y.: Fructose-induced metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells (2024) Frontiers in Immunology | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1375461.

Zelenka, L.: Fructose-induced anxiety (2025) Nature Neuroscience | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02019-9.

Zhao, Q. et al.: Targeting fructose metabolism for cancer therapy (2025) Cancer Letters | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217914.