This is the second in a series of five blogs where I’ll discuss how metabolomics is set to transform medicine as we know it. The applications of omics in biomedical research are vast, and to help organize the different ways metabolomics can be used, I’ll discuss this in the context of 5P medicine.

If you are already familiar with the concept of 5P medicine and how omics contribute to the transformation of medicine, click to move forward to the predictive medicine section of this blog.

An introduction to 5P medicine

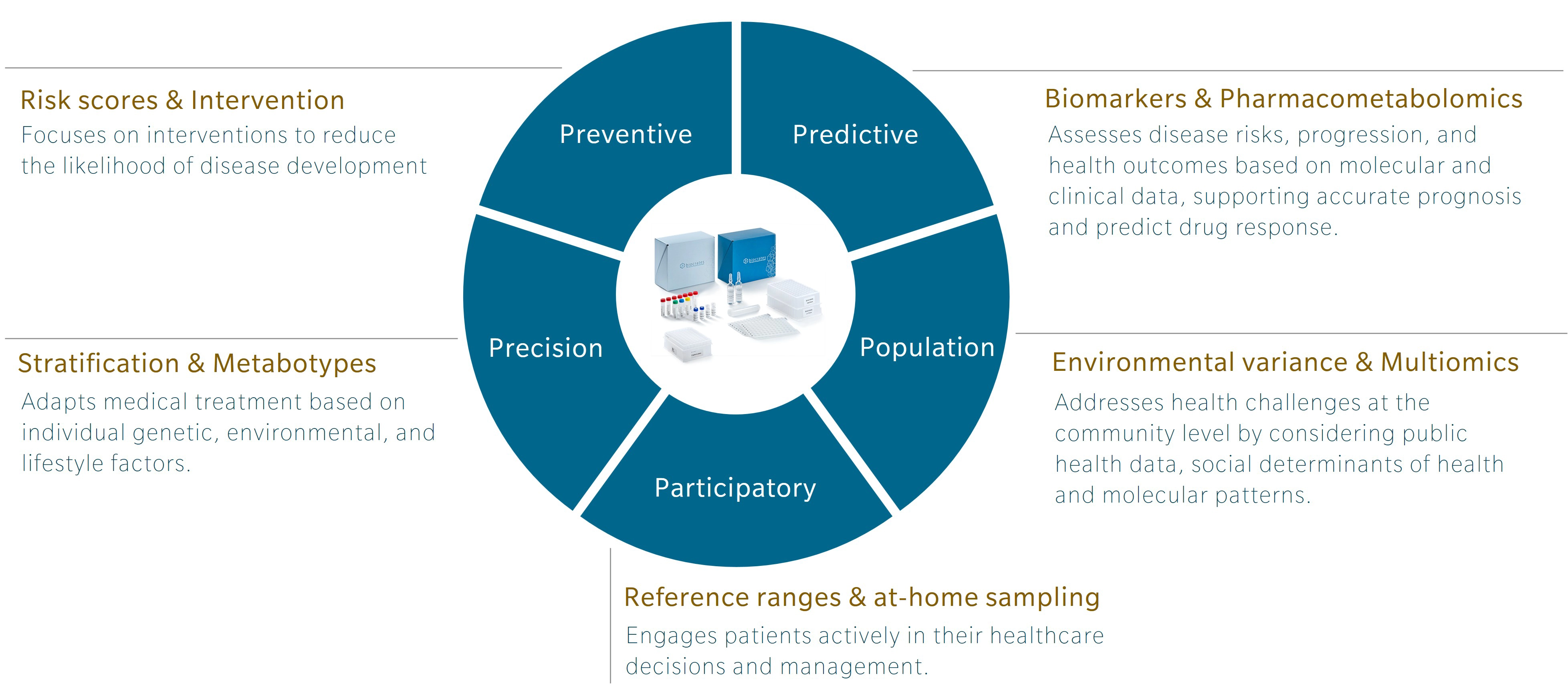

5P medicine is a concept developed to address the limitations of traditional Western medicine, which typically focuses on reacting to illness or injury. Making use of five components – preventive, predictive, precision, participatory and population-based medicine – 5P medicine aims to shift the focus towards a more proactive and patient-centric practice.

Personally, I first encountered this concept in a book by Leroy Hood and Nathan Price, The Age of Scientific Wellness. Hood and Price describe what they call P4 medicine. Rather than the familiar model that treats or manages disease after its occurrence, the authors offer an alternative that leverages the scientific tools at our disposal to understand health and disease. The result is a transition from what they call a “sickcare” system towards a genuine “healthcare” system. The 5P model expands this concept by adding population-based medicine to the original four and incorporating strategies that use the power of large cohort studies to find additional insights.

Omics and the future of research and health

Omics research has been around for over 30 years, and while genomics is gaining traction and beginning to be used in the clinics, other omics, and multiomics integration, are still lagging. Each omic addresses a distinct layer of biology, with its own codes, regulatory signals and sensitivity to external influences that offer unique insights.

Genomics is the layer least influenced by environment once a person is born. Of course, mutations can occur and change someone’s DNA, but these happen locally and are most often corrected. In contrast, metabolomics is the layer most sensitive to the environment. It responds to our diet, lifestyle, and exposures. For example, metabolomics profiles can shift in response to year after year of terrible food choices. Poor diet usually leads to chronic low-grade inflammation, which presents metabolic patterns closely associated with markers of inflammation at the granular level (Pietzner et al. 2017).

Genomics can tell you about your risk of developing an inflammatory disease, but it cannot track changes throughout your life. Similarly, genomics can identify mutations that will influence response to a specific drug, but it does not respond to influences from the environment that determine our drug response. Metabolomics can. That’s exactly why it’s such a great tool for predictive medicine.

Learn more about the power of multiomics for 5P medicine in my webinar.

Predictive medicine with metabolomics

A person’s metabolome can provide a wealth of information regarding disease trajectory, disease stage, and their likelihood to respond to a specific therapy.

At the intersection of disease prognosis, personalized treatments, and metabolomics, some of the most interesting applications include:

- Prognosis – Predicting disease trajectory

- Pharmacometabolomics | Understanding patients’ drug response with the metabolome

Prognosis

Metabolites have long been used as biomarkers for prognosis. For example, the ratio of blood levels of the nitrogen-carrying metabolites urea and creatinine is a marker of renal function commonly used in the clinics. This ratio is also elevated in other related ailments, including heart disease and sepsis.

On the third season of The Metabolomist podcast, I discussed cancer prognosis and survival prediction with Robert Nagourney. In the episode, he highlighted a recent publication on pancreatic cancer, which showed that metabolomics signatures enabled earlier disease prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) than traditional tumor markers or radiographic measures (D’Amora et al. 2024). In addition, metabolomics profiling provided mechanistic insights into disease severity that enabled the stratification of patient into sub-groups based on their metabolome. Using metabolite concentrations in patient samples, predictive models were developed to improve prognosis accuracy. Specifically, metabolomics-based models achieved high predictive performance (AUC up to ~0.90), allowing better stratification of patients according to their survival risk and supporting more personalized and effective treatment decisions.

Pharmacometabolomics

Pharmacometabolomics studies interactions between the metabolome and pharmaceutical drugs, with applications in both clinical practice and drug development. We’ve already discussed an example of how metabolomics can predict patient response to treatment in last month’s article on preventive medicine. In brief, (Tintelnot et al. 2023) identified the tryptophan metabolite 3-indole acetic acid (3-IAA) as a modulating factor in chemotherapy response. Using a broad targeted panel of metabolites, the researchers were able to link 3-IAA synthesis in the gut microbiome and its influence on the patient’s immune system. They proposed a simple yet effective solution: supplementing 3-IAA to increase response rate. This worked in an animal model of PDAC, though it has still to be investigated in humans.

This example reflects a widely adopted and effective three-tiered approach in pharmacometabolomics:

- Screen samples with a broad metabolomics panel for biomarkers and mechanistic insights;

- Leverage data using a combination of bioinformatic tools and knowledge of biochemistry and physiology;

- Translate insights into innovative solutions that will support 5P medicine.

This strategy is replicated throughout the literature. For instance, broad metabolomics profiling identified a pattern of elevated polyamines and lysophospholipids (specifically lysophosphatidylcholines and lysophosphatidylethanolamines) that accurately predicts poor response to CAR-T cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (Fahrmann et al. 2022). High levels of acetylated polyamines correlated with worse progression-free and overall survival. The findings align with previous evidence showing an effect on acetylated polyamines in several cancer types (Li et al. 2020).

Outlook

Metabolomics offers a wealth of information to support a predictive approach to disease. Broad panels of metabolites enable a deep screen of the metabolome that will “sense” changes, often in multiple pathways at once. This makes use of the interconnected nature of the metabolome, where changes in one metabolite can affect a vast number of pathways.

Careful study design is essential to limit the number of confounders that may bias the analysis. Expert analysis is equally important to extract meaningful insights from the data. Unsupervised analyses of large datasets are a wonderful source of original findings, however, the final interpretation to leverage the data must be done in light of our current knowledge of metabolism and medicine, as I explain in my book on metabolomics data interpretation The STORY principle. Databases such as MetaboINDICATOR, which catalogue known changes associated with disease and calculate sums and ratios of metabolites known to associate with different health states, can provide a useful ‘pre-interpretation’ of results.

Ultimately, these insights are only the starting point for developing innovative solutions, whether to predict a person’s prognosis, treatment response or disease progression. You’ll notice that the link between this predictive approach and precision medicine is never far. In next month’s blog, we’ll dive deeper into the ways that metabolomics is used in precision medicine.

Sign up for our newsletter to be notified when the next blog on 5P medicine comes out.

References

Pietzner et al.: Plasma proteome and metabolome characterization of an experimental human thyrotoxicosis model (2017) BMC Medicine | http://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0770-8

Sakr et al.: The prognostic role of urea-to-creatinine ratio in patients with acute heart failure syndrome: a case–control study (2023) Egypt Heart J | https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-023-00404-y

D’Amora et al.: Diagnostic and prognostic performance of metabolic signatures in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: The clinical application of quantitative NextGen mass spectrometry (2024) Metabolites | https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14030148

Tintelnot et al.: Microbiota-derived 3-IAA influences chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic cancer (2023) Nature | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05728-y

Fahrmann et al.: A polyamine-centric, blood-based metabolite panel predictive of poor response to CAR-T cell therapy in large B cell lymphoma (2022) Cell Rep Med.| https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100720

Li et al.: Polyamines and related signaling pathways in cancer (2020) Cancer Cell Int.| https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-020-01545-9