This is the last in a series of five blogs where I’ll discuss how metabolomics is set to transform medicine as we know it. The applications of omics in biomedical research are vast, and to help organize the different ways metabolomics can be used, I’ll discuss this in the context of 5P medicine.

If you are already familiar with the concept of 5P medicine and how omics contribute to the transformation of medicine, click to move forward to the participatory medicine section of this blog.

An introduction to 5P medicine

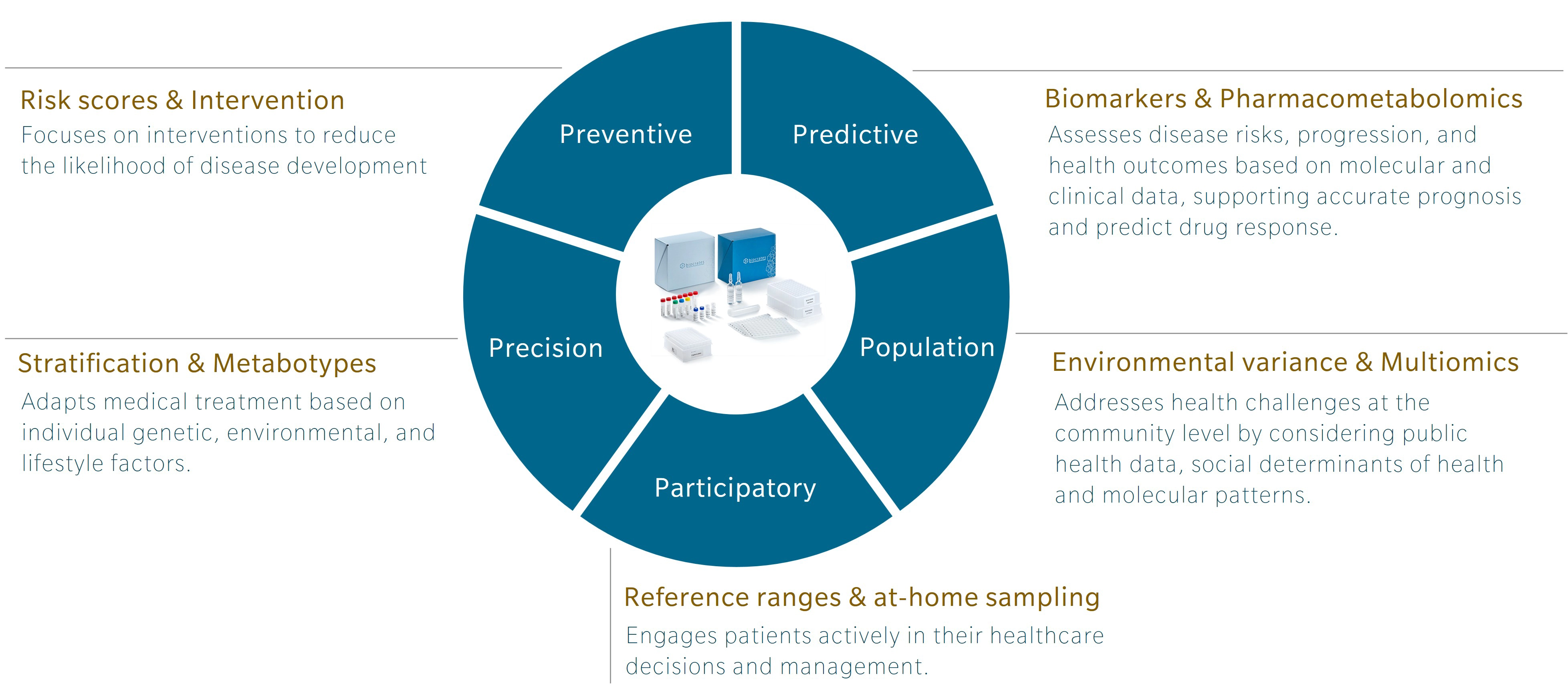

5P medicine is a concept developed to address the limitations of traditional Western medicine, which typically focuses on reacting to illness or injury. Making use of five components – preventive, predictive, precision, participatory and population-based medicine – 5P medicine aims to shift the focus towards a more proactive and patient-centric practice.

Personally, I first encountered this concept in a book by Leroy Hood and Nathan Price, The Age of Scientific Wellness. Hood and Price describe what they call P4 medicine. Rather than the familiar model that treats or manages disease after its occurrence, the authors offer an alternative that leverages the scientific tools at our disposal to understand health and disease. The result is a transition from what they call a “sickcare” system towards a genuine “healthcare” system. The 5P model expands this concept by adding population-based medicine to the original four and incorporating strategies that use the power of large cohort studies to find additional insights.

Omics and the future of research and health

Omics research has been around for over 30 years, and while genomics is gaining traction and beginning to be used in the clinics, other omics, and multiomics integration, are still lagging. Each omic addresses a distinct layer of biology, with its own codes, regulatory signals and sensitivity to external influences that offer unique insights.

Genomics is the layer least influenced by environment once a person is born. Of course, mutations can occur and change someone’s DNA, but these happen locally and are most often corrected. In contrast, metabolomics is the layer most sensitive to the environment. It responds to our diet, lifestyle, and exposures. For example, metabolomics profiles can shift in response to year after year of terrible food choices (Limonciel et al. 2013). Poor diet usually leads to chronic low-grade inflammation, which presents metabolic patterns closely associated with markers of inflammation at the granular level (Pietzner et al. 2017).

Genomics can tell you about your risk of developing an inflammatory disease, but it cannot track how this risk evolves throughout your life. Similarly, genomics can identify genotypes that will influence response to a specific drug, but it does not respond to influences from the environment that determine our drug response. Metabolomics can. That’s exactly why it’s such a great tool for population-based medicine where the need for measures of disease risk beyond genetic predisposition is high.

Learn more about the power of multiomics for 5P medicine in my webinar.

Participatory medicine with metabolomics

Participatory medicine puts the patient at the center of medical care. Often, patients begin collecting biological data even before clinical symptoms appear, enabling earlier detection of potential health issues, which aligns closely with the aims of preventive medicine. A growing number of companies offer services that allow individuals to get a detailed picture of their health at their own request. Starting with genomics in the 2000s, and soon followed by epigenomics, microbiomics, proteomics and now metabolomics, these “consumer health” companies made omics much more accessible to the general public, though usually still paid for by the individual.

Traditional healthcare systems are beginning to catch up, with genomics now included in routine investigations, for example in cancer prevention and treatment. Laboratories now also offer other omics-based tests, including metabolomics, expanding the range of biomarkers available in medical practice.

Sample collection to make healthcare more accessible

When you go to your doctor or to the hospital and a sample is needed, they will usually take blood. However, this collection method has several drawbacks when it comes to making medicine accessible: not only is it invasive, but it also requires trained medical staff to perform phlebotomy, which often means you need to travel to have your sample taken.

There are alternatives that allow individuals to collect their blood themselves, either on a filter paper card or on a more complex device. These at-home microsampling devices are less invasive and better suited to use with children and sensitive populations, supporting a more compassionate and patient-friendly model of care.

For metabolomics and lipidomics, analyte stability can be a concern. Because collection devices are often shipped at room temperature over several days, there’s a real risk that some analytes will degrade, compromising the interpretability of results. This must be mitigated to make the most of this convenient sampling method.

In a recent application note, we compared the stability of the metabolites covered by the MxP® Quant 500 kit and the reproducibility of quantification in samples collected with classical dried blood spots (DBS) and Neoteryx’s Mitra® tips. The results show that different analytes are affected to different degrees, depending on the device used. This information should be taken into account when planning experiments with these devices.

Many analytes are known to degrade quickly at room temperature, which can either reduce their measured concentration, or increase the concentration of their degradation products in a sample. Rather than being seen as a concern, this simply needs to be documented to inform interpretation of the results. Typically, one would remove the analytes with known instability from the analysis and focus on the ones that are more stable.

Blood is the most commonly used sample type, but other matrices bring added value when painting the picture of a patient’s health. Urine has been used for a long time in the clinics, sometimes after collection of large volumes at home. Today, devices exist to sample only a fraction of urine samples to be sent to the laboratory for analysis.

Similarly, feces are gaining momentum, especially for the combined analysis of the metabolome and the microbiome. For routine measurement, devices optimized to sample a fraction of feces samples were developed, with varying degrees of suitability for metabolomic analysis. In our recent application note, we compared the detectability and stability of metabolites measured with our SMartIDQ alpha kit in feces samples collected with two at-home sampling devices. Here again, differences exist and will determine the best device to be used for each study.

Overall, combining at-home collection using microsampling devices with mass spectrometry-based metabolomics and lipidomics is an effective way to assess a person’s metabolome from the comfort of their own home. Today, this may appeal primarily to people who can afford the services of private consumer health companies, but tomorrow these technologies will make it possible for any family doctor to request tests for patients living in remote locations or to support a virtual consultation.

The need for reference ranges

To interpret metabolomic profiles reliably, reference ranges are essential. Just as clinicians rely on known normal ranges for commonly measured metabolites like glucose, understanding what constitutes a “normal” value for each metabolite is key to drawing meaningful conclusions.

Establishing such reference ranges can be cumbersome, and laboratories that measure these values routinely will typically create their own set of reference measurements from “healthy controls,” which builds over time. The concentration range for glucose tends to be tightly regulated no matter which part of the (healthy) population one looks at. However, it can be useful to create more tailored ranges when looking at a broad range of metabolites that are influenced by exposures, diet and other factors.

Take creatine, for example – a metabolite involved in energy metabolism and widely used as a supplement by athletes. Blood concentration of creatine can vary greatly between women and men, across ethnicities and depending on an individual’s diet and supplement use. Having a reference range tailored to the person’s gender, age, ethnicity, diet and exercise level will enable a more accurate interpretation of their metabolomic profile.

Tools such as the quantitative metabolomics database (QMDB) support more meaningful interpretation by providing reference ranges that can be filtered and tailored to the specifics of each person’s biology and lifestyle. Currently, the database focuses on reference ranges in human plasma, but in future the same approach could be applicable for blood microsampling devices and other matrices, too.

Outlook

Metabolomics that comes in a quantitative and standardized shape is ideally suited to a participatory medicine approach. The small sample volumes collected with at-home sampling devices can be analyzed and interpreted in light of the known variations in analyte concentrations that occur due to sample degradation at room temperature.

Once measured, comparison to a relevant reference range enables the results measured in the laboratory to be translated into actionable health insights. These interpretations are made by medical doctors based on known “normal” concentration ranges and known causes of deviation. Creating appropriate reference ranges will be a vital step in extending this approach in remote areas and in populations that are not currently well represented in reference healthy populations. Tools like QMDB promise to facilitate access to such reference ranges, especially for scientists who do not yet have access to robust reference data.

While metabolomics and lipidomics are most often associated with blood plasma, we will likely have a broader range of collection devices to choose from in future, each with its own set of reference ranges. This will not only expand access to healthcare for patients, but it will also support the faster translation of omics into clinics and medical practice.

This blog concludes our five-part series on 5P medicine. I hope I have sparked your interest in this exciting new way of looking at medicine – putting the patient in the center, learning from multi-scale data, and focusing on real-life improvements in patient care, disease understanding and drug discovery.

To hear more about how (metabol)omics contributes to personalized, predictive and precision medicine, please sign up for our newsletter and listen to season 4 of The Metabolomist podcast.

Learn more about 5P medicine in our other articles:

References

Grant et al.: Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes (2006) Nature Genetics | https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1732

Helgadottir et al.: A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction (2007) Science | https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1142842

Hoffman et al.: Development of a metabolomic risk score for exposure to traffic-related air pollution: A multi-cohort study (2024) Environmental Research | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.120172

Kelly et al.: Metabo-endotypes of asthma reveal differences in lung function: Discovery and validation in two TOPMed cohorts (2021) ATS | http://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202105-1268OC

Lacruz et al.: Instability of personal human metabotype is linked to all-cause mortality (2018) Nature | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27958-1

Limonciel et al.: Complex chronic diseases have a common origin (2013) I https://biocrates.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/biocrates-Complex-chronic-diseases-have-a-common-origin.pdf

Ogishima et al.: dbTMM: an integrated database of large-scale cohort, genome and clinical data for the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project (2021) Human Genome Variation | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-021-00175-5

Pietzner et al.: Plasma proteome and metabolome characterization of an experimental human thyrotoxicosis model (2017) BMC Medicine | http://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0770-8

Prince et al.: Phenotypically driven subgroups of ASD display distinct metabolomic profiles (2023) Brain, Behavior, and Immunity | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.03.026

So et al.: Evaluating the heritability explained by known susceptibility variants: a survey of ten complex diseases (2011) Genetic Epidemiology | https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.20579