- History & Evolution

- Biosynthesis & dietary uptake

- p-cresol glucuronide and nephrology

- p-cresol glucuronide and cardiometabolic disease

- p-cresol glucuronide and neurology

- p-cresol glucuronide and cancer

- p-cresol glucuronide and 5P medicine

- References

History & Evolution

Early 1990s: first studies on p-cresol

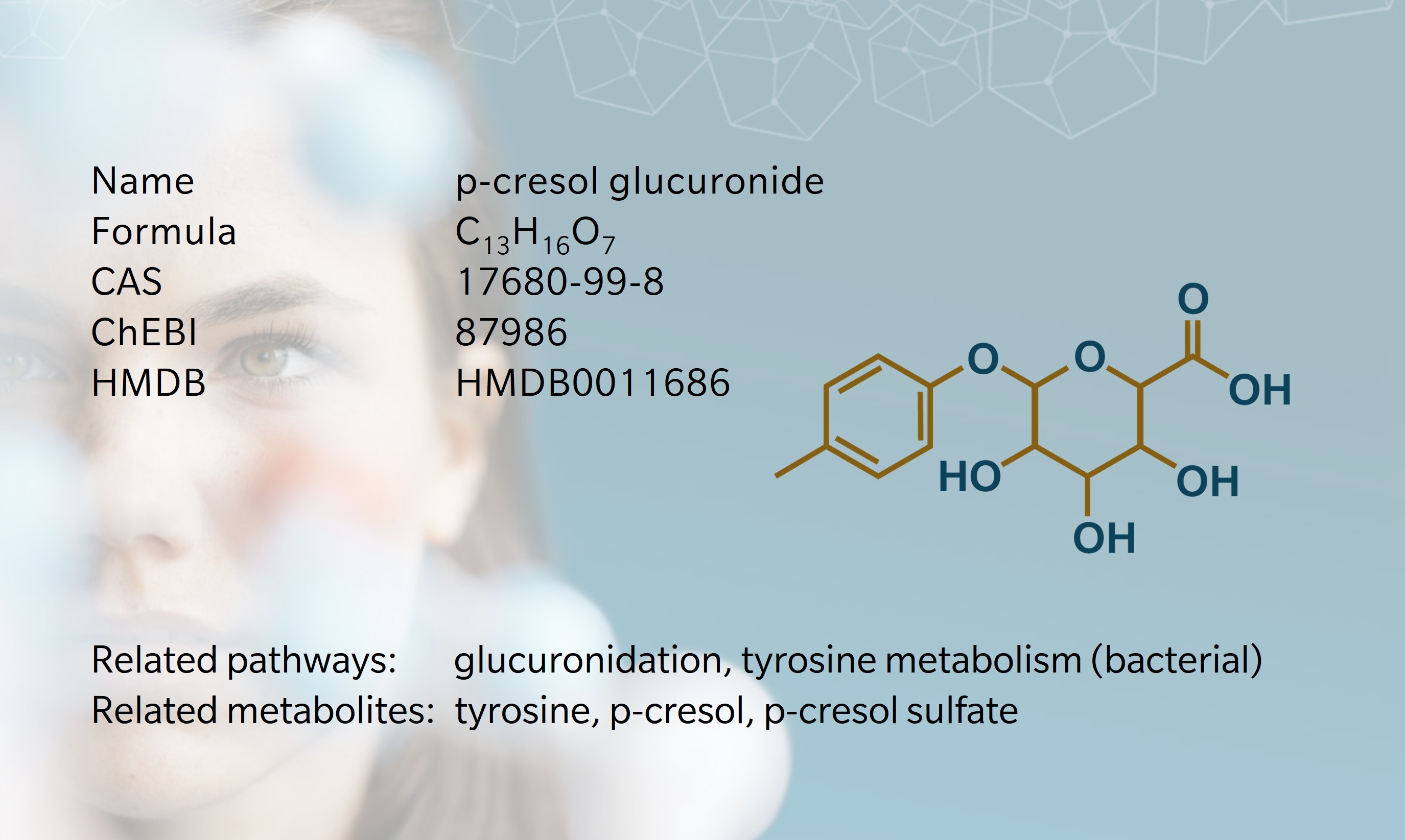

p-cresol glucuronide is a modified form of the gut-microbial metabolite p-cresol, synthesized in the liver to promote excretion through the urine. p-cresol is derived from bacterial proteolytic fermentation of tyrosine (Diether et al. 2019). Early uremia research often (mis)attributed circulating toxicity to unconjugated p-cresol, but improved analytics overturned this view. The current paradigm is that gut-derived p-cresol is rapidly conjugated across the colonic mucosa and in the liver, yielding chiefly p-cresol sulfate (pCS) and a smaller pool of p-cresol glucuronide (pCG), with free p-cresol usually undetectable (Soulage et al. 2022). The notion of unconjugated p-cresol as a uremic toxin is a “historical artefact” (Soulage et al. 2022) arising from acid or heat deproteinization that hydrolyzed conjugates during sample preparation.

Because research centered on pCS, pCG received comparatively little attention. A practical reason is that authentic pCG only became readily available as a commercial reference standard in the late 2000s (Koppe et al. 2017), slowing targeted quantification and mechanistic work until vendors supplied it. Despite higher total concentrations of pCS, differing albumin affinities leave pCS and pCG with comparably sized free fractions in serum (Liabeuf et al. 2013). Over time, pCG has moved from an overlooked “detox conjugate” to a recognized and valuable measure linking microbiome and host health.

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

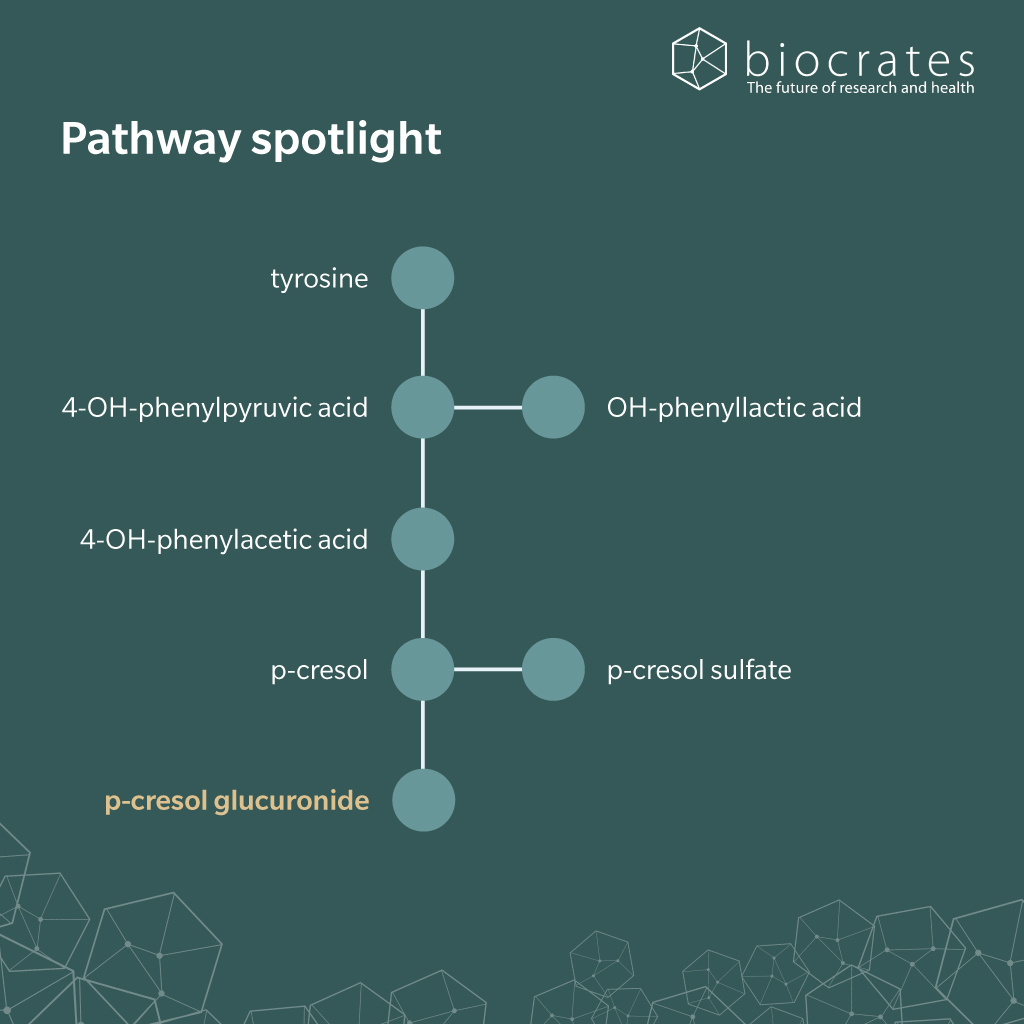

There appears to be no significant dietary pCG intake. However, diet shapes pCG levels indirectly by modulating colonic proteolysis. More total protein and aromatic amino acids increase substrate load, while fiber (Salmean et al. 2015), resistant starch (Snelson et al. 2024), and certain prebiotics (Meijers et al. 2010) steer carbon toward short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and away from tyrosine fermentation (Snelson et al. 2024).

In the gut, tyrosine is first converted to 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid and then decarboxylated to p-cresol, after which p-cresol crosses the mucosa and enters the portal circulation. During first-pass metabolism in the colon and the liver, phase II enzymes rapidly conjugate p-cresol: sulfotransferases yield pCS (Rong et al. 2021; Stachulski et al. 2023) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) yield pCG (Rong et al. 2020). In the bloodstream, renal organic anion transporters OAT1/3 take up pCG and pCS for tubular secretion, leading to excretion through the urine. When kidney function or transporter capacity is reduced, both conjugates accumulate systemically (Wu et al. 2017), supporting their classification as uremic toxins.

p-cresol glucuronide and nephrology

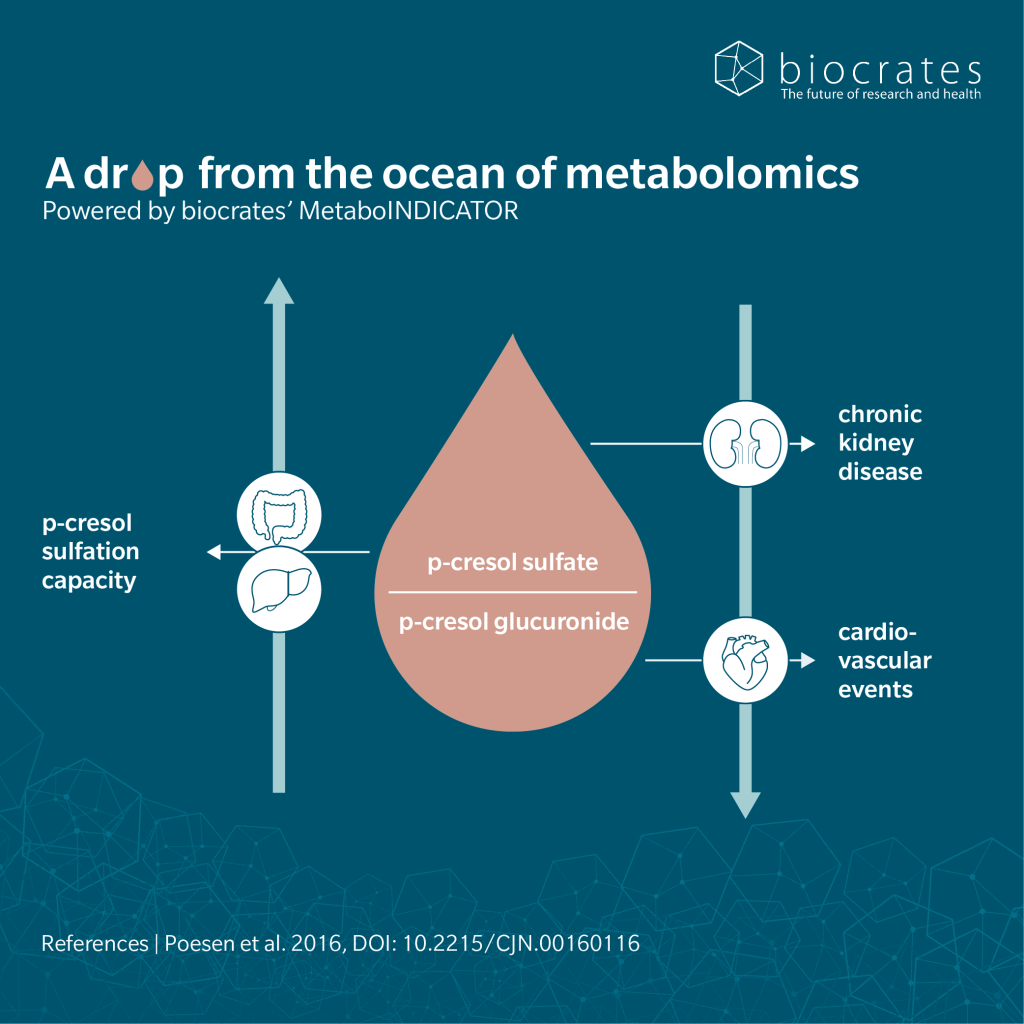

In nephrology, pCG is clinically relevant: as glomerular filtration and tubular secretory capacity fall, pCG accumulates in serum, reaching even higher levels in hemodialysis (Peters et al. 2023; Liabeuf et al. 2013). Accordingly, pCG is considered a microbiome-derived uremic toxin linking gut ecology with renal outcomes.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) reduces gut microbial diversity and induces compositional shifts (Peters et al. 2023). In a prospective cohort, pCG associated with greater estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) loss over six years, showing that higher pCG tracks kidney decline (Peters et al. 2023). Furthermore, total and free pCG in serum rise with CKD severity, and higher pCG predicts overall and cardiovascular mortality, with risk prediction similar to pCS (Liabeuf et al. 2013). Beyond reflecting burden, pCG can perturb proximal tubular phenotype, inducing epithelial–mesenchymal transition markers, transporter dysregulation, and cellular stress in human renal proximal tubular cells. Notably, pCS did not affect cellular stress in the same system (Mutsaers et al. 2015).

Together, these lines of evidence support ongoing evaluation of pCG as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker across CKD stages (Choudhary et al. 2025).

p-cresol glucuronide and cardiometabolic disease

Compared with its sulfate counterpart and the parent phenol, pCG appears less cytotoxic across human kidney, liver, and blood cell models; a pattern consistent with glucuronidation serving primarily as detoxification (Zhu et al. 2021; Bertarini et al. 2025). Nevertheless, its cardiometabolic relevance remains unsettled, with context-dependent findings that do not point uniformly toward a role as toxin or detoxicant.

In a prospective analysis in CKD patients, the total p-cresol burden (pCS + pCG) in serum associated with mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Importantly the conjugation pattern mattered: a lower pCS/pCG ratio, so a relative shift toward glucuronidation, was independently associated with higher risks of mortality and CVD (Poesen et al. 2016). At the same time, metabolic effects diverged between conjugates, since in mouse and cellular models, pCG did not induce insulin resistance, whereas pCS did (Koppe et al. 2017). In liver models, the parent compound p-cresol induced pronounced oxidative stress, glutathione depletion, and necrotic cell death. In contrast, pCG showed minimal cytotoxicity in hepatocytes and behaved as a detoxification product rather than a toxin, making it unlikely to mediate the hepatic toxic effects attributed to p-cresol (Zhu et al. 2021).

Diet–microbiome evidence links pCG to hypertension and diabetes biology. In diabetic mice, uremic toxins, including pCG, were elevated in plasma. Resistant starch supplementation lowered pCG, strengthened the intestinal barrier and dampened renal inflammation as indicated by fewer neutrophils and lower complement activation. Finally, resistant starch reduced albuminuria, supporting a renoprotective effect of pCG in diabetes (Snelson et al. 2024).

In humans, low fiber intake associated with higher circulating pCG and higher blood pressure. In a randomized trial, SCFA-enriched fiber reduced both plasma pCG and blood pressure, consistent with a microbiota-mediated shift toward reduced tyrosine fermentation (Xu et al. 2025).

p-cresol glucuronide and neurology

As a host–microbe co-metabolite, pCG sits on the gut–brain axis. Although glucuronides are often considered inert (Bertarini et al. 2025), converging evidence suggests that pCG can be biologically active at the cerebral endothelium. In mice, pCG strengthened blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity and reshaped the whole-brain transcriptome (Stachulski et al. 2023; Bertarini et al. 2025).

In human brain microvascular endothelial cells, pCG alone had little effect but prevented LPS-induced barrier permeability when co-applied, acting as a functional antagonist at toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Stachulski et al. 2023). These findings support a context-dependent, neuroprotective role against pro-inflammatory stimuli under physiological conditions (Bertarini et al. 2025).

Population data are bidirectional: higher urinary p-cresol, pCS, and pCG have been reported in autistic children (Bertarini et al. 2025; Gabriele et al. 2014), whereas in children with CKD, pCG did not associate with neurological outcomes (Ebrahimi et al. 2025). In Parkinson’s disease cohorts, serum pCG was elevated alongside p-cresol and pCS in patients (Paul et al. 2023) and plasma pCG positively correlated with motor symptom severity (Chen et al. 2023). Evidences from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research showed higher pCG levels in patients together with adverse brain aging and cognitive decline (Gordon et al. 2024).

p-cresol glucuronide and cancer

Metabolomics has contributed to placing pCG on the oncology map, not as a causal driver, but rather as a non-invasive urinary biomarker. In renal cell carcinoma, an independent validation cohort confirmed higher urinary pCG at diagnosis and still elevated one year post-nephrectomy (Oto et al. 2025). In colorectal cancer, urinary profiles of pCG across disease and recovery windows after surgery showed upregulation in disease stage 3-4 and downregulation in stage 0-2, suggesting stage-linked pCG variation (Fu et al. 2024; Liesenfeld et al. 2015). Similarly, a prospective study of bladder cancer (BC) patients validated urinary pCG as a diagnostic biomarker, and notably within non-muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC), as a staging biomarker (Oto et al. 2022).

p-cresol glucuronide and 5P medicine

Biomarkers predict treatment response, monitor progression, stratify risk, and enable precision care, serving several aims of 5P medicine. In blood, pCG levels rise with declining renal function and pCG has been suggested as diagnostic and prognostic marker across CKD stages (Choudhary et al. 2025).

Owing to its excretion fate, pCG is also a relevant marker in urine, a compelling non-invasive matrix for predictive and diagnostic applications in oncology (Liesenfeld et al. 2015; Oto et al. 2022). Urine reflects renal excretion, including short-term changes induced by diet or drugs, more rapidly than blood.

As a biomarker, pCG is also actionable. Diet and microbiome interventions, especially fermentable fibers/resistant starch, can lower circulating pCG levels (Snelson et al. 2024; Xu et al. 2025), supporting the preventive, predictive and participatory pillars of 5P medicine. Especially in combination with other uremic toxins like indoxyl sulfate or p-cresol sulfate , pCG can sharpen risk predictions, clarify mechanisms, and improve precision healthcare.

References

Bertarini, L. et al.: Para-Cresol and the Brain: Emerging Role in Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Therapeutic Perspectives (2025) ACS pharmacology & translational science | https://doi.org/10.1021/acsptsci.5c00289.

Chen, S.-J. et al.: Plasma metabolites of aromatic amino acids associate with clinical severity and gut microbiota of Parkinson’s disease (2023) npj Parkinson’s Disease | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-023-00612-y.

Choudhary, B.B. et al.: Novel molecular biomarkers in kidney diseases: bridging the gap between early detection and clinical implementation (2025) Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology | https://doi.org/10.1093/jpp/rgaf096.

Diether, N.E. et al.: Microbial Fermentation of Dietary Protein: An Important Factor in Diet⁻Microbe⁻Host Interaction (2019) Microorganisms | https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7010019.

Ebrahimi, M. et al.: Investigation of a targeted panel of gut microbiome-derived toxins in children with chronic kidney disease (2025) Pediatric Nephrology | https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-024-06580-6.

Fu, C. et al.: The Potential of Metabolomics in Colorectal Cancer Prognosis (2024) Metabolites | https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14120708.

Gabriele, S. et al.: Urinary p-cresol is elevated in young French children with autism spectrum disorder: a replication study (2014) Biomarkers | https://doi.org/10.3109/1354750X.2014.936911.

Gordon, S. et al.: Metabolites and MRI-Derived Markers of AD/ADRD Risk in a Puerto Rican Cohort (2024) Research square | https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3941791/v1.

Koppe, L. et al.: p-Cresyl glucuronide is a major metabolite of p-cresol in mouse: in contrast to p-cresyl sulphate, p-cresyl glucuronide fails to promote insulin resistance (2017) Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation | https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfx089.

Liabeuf, S. et al.: Does p-cresylglucuronide have the same impact on mortality as other protein-bound uremic toxins? (2013) PLoS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067168.

Liesenfeld, D.B. et al.: Changes in urinary metabolic profiles of colorectal cancer patients enrolled in a prospective cohort study (ColoCare) (2015) Metabolomics | https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-014-0758-3.

Meijers, B.K.I. et al.: p-Cresyl sulfate serum concentrations in haemodialysis patients are reduced by the prebiotic oligofructose-enriched inulin (2010) Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association – European Renal Association | https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfp414.

Mutsaers, H.A.M. et al.: Proximal tubular efflux transporters involved in renal excretion of p-cresyl sulfate and p-cresyl glucuronide: Implications for chronic kidney disease pathophysiology (2015) Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2015.07.020.

Oto, J. et al.: LC-MS metabolomics of urine reveals distinct profiles for non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (2022) World Journal of Urology | https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-022-04136-7.

Oto, J. et al.: Validation of urine p-cresol glucuronide as renal cell carcinoma non-invasive biomarker (2025) Journal of Proteomics | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2024.105357.

Paul, K.C. et al.: Untargeted serum metabolomics reveals novel metabolite associations and disruptions in amino acid and lipid metabolism in Parkinson’s disease (2023) Molecular Neurodegeneration | https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-023-00694-5.

Peters, B.A. et al.: Association of the gut microbiome with kidney function and damage in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) (2023) Gut Microbes | https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2023.2186685.

Poesen, R. et al.: Metabolism, Protein Binding, and Renal Clearance of Microbiota-Derived p-Cresol in Patients with CKD (2016) Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN | https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00160116.

Rong, Y. et al.: Characterizations of Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Enzymes in the Conjugation of p-Cresol (2020) Toxicological Sciences | https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfaa072.

Rong, Y. et al.: Characterization of human sulfotransferases catalyzing the formation of p-cresol sulfate and identification of mefenamic acid as a potent metabolism inhibitor and potential therapeutic agent for detoxification (2021) Toxicology and applied pharmacology | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2021.115553.

Salmean, Y.A. et al.: Fiber supplementation lowers plasma p-cresol in chronic kidney disease patients (2015) Journal of renal nutrition : the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation | https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2014.09.002.

Snelson, M. et al.: Dietary resistant starch enhances immune health of the kidney in diabetes via promoting microbially-derived metabolites and dampening neutrophil recruitment (2024) Nutrition & Diabetes | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-024-00305-2.

Soulage, C.O. et al.: The very last dance of unconjugated p-cresol… historical artefact of uraemic research (2022) Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation | https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfab325.

Stachulski, A.V. et al.: A host-gut microbial amino acid co-metabolite, p-cresol glucuronide, promotes blood-brain barrier integrity in vivo (2023) Tissue Barriers | https://doi.org/10.1080/21688370.2022.2073175.

Wu, W. et al.: Key Role for the Organic Anion Transporters, OAT1 and OAT3, in the in vivo Handling of Uremic Toxins and Solutes (2017) Scientific Reports | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04949-2.

Xu, C. et al.: Lack of dietary fibre increases gut microbiome-derived uremic toxins that contribute to increased blood pressure (2025) medRxiv | https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.09.16.25335853.

Zhu, S. et al.: Effects of p-Cresol on Oxidative Stress, Glutathione Depletion, and Necrosis in HepaRG Cells: Comparisons to Other Uremic Toxins and the Role of p-Cresol Glucuronide Formation (2021) Pharmaceutics | https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13060857.