- History & Evolution

- Biosynthesis & dietary uptake

- cAMP and cell signaling

- cAMP and neurology

- cAMP and oncology

- cAMP and 5P medicine

- References

History & Evolution

1957 – 1958: discovery of role as second messenger | 1971: Nobel Prize

Earl Sutherland and colleagues identified cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) as a second messenger that relays hormone signals inside cells. This work earned Sutherland the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1971 (Kresge et al. 2005). Over the next decades, cAMP emerged as a universal signaling molecule, coordinating metabolism, gene expression, cardiac contractility, neurotransmission, and immune responses across tissues and species (Patra et al. 2023). Remarkably, cAMP levels can rise and fall within seconds, allowing cells to respond dynamically to external stimuli (Jiang et al. 2007). In humans, everyday substances like caffeine modulate cAMP signaling by subtly amplifying the molecule’s effects on alertness and metabolism (Barcelos et al. 2020). Its influence also extends beyond multicellular organisms: bacteria use cAMP to regulate their nutrient uptake (You et al. 2013), while in social amoebae such as Dictyostelium discoideum, cAMP acts as a “social molecule”, guiding collective movement and aggregation (Brimson et al. 2025).

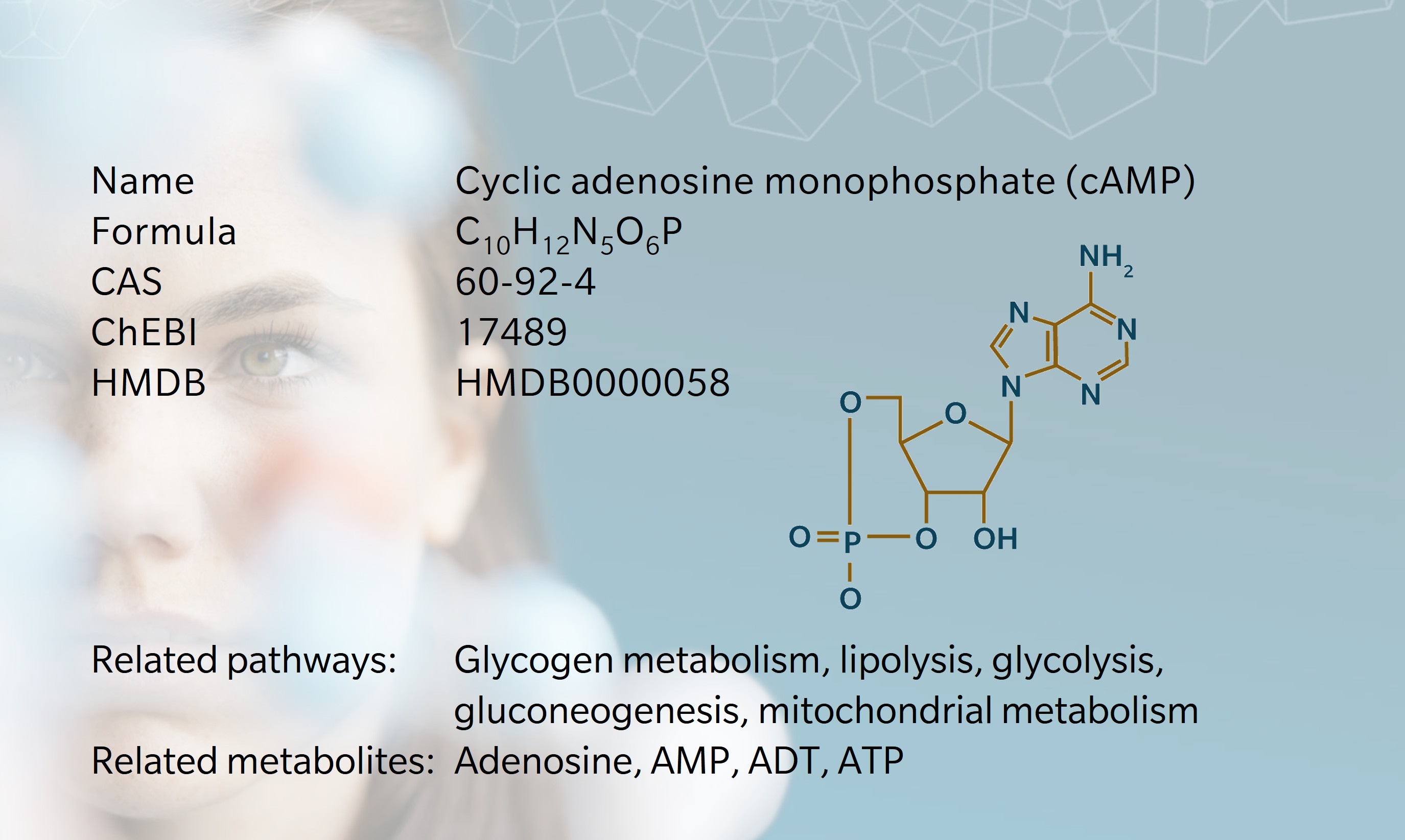

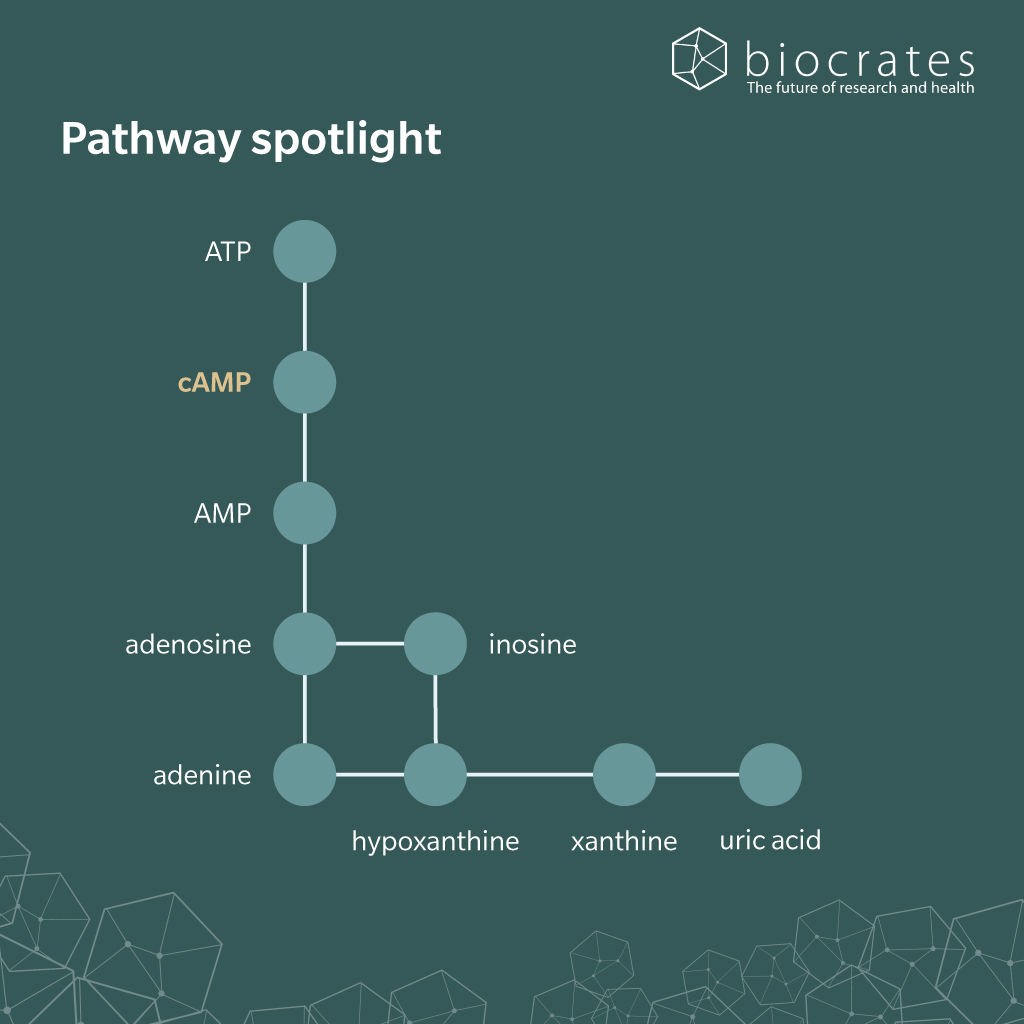

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

There is no indication that cAMP is absorbed from the diet. In contrast, cAMP is synthetized from ATP by adenylyl cyclase (AC), a plasma membrane-bound intracellular enzyme. The activity of AC is sensitive to numerous stimuli, including hormones and neurotransmitters, through the action of a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), comprising several regulatory subunits; e.g. the stimulatory Gαs subunit, and the inhibitory Gαi subunit (Yadav et al. 2025). Activated AC converts adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into cAMP, which functions as a second messenger to drive downstream signaling. After the signal is transduced, cAMP signaling is terminated primarily by phosphodiesterases (PDE) that hydrolyze it to 5’-adenosine monophosphate (AMP), a form that lacks signaling activity (Patra et al. 2023). Although cAMP is primarily expected within cells, it is also quantifiable in blood, urine (Piec et al. 2017), saliva (Henkin et al. 2007) and cerebrospinal fluid (Oeckl et al. 2012).

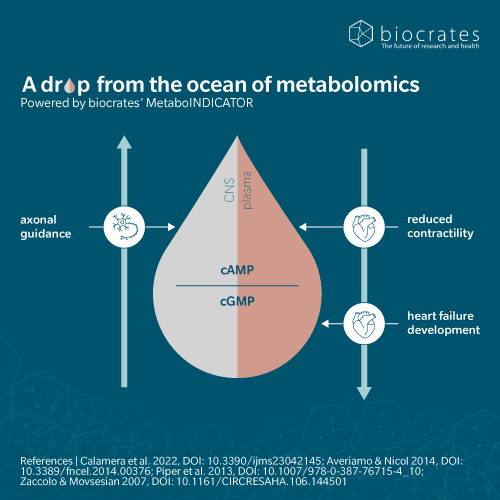

cAMP and cell signalling

cAMP is a ubiquitous second messenger that translates extracellular cues into precise cellular actions. Its principal effector is protein kinase A (PKA): cAMP binding activates PKA, which phosphorylates serine/threonine residues on target proteins. A classic example is phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which regulates gene transcription (Patra et al. 2023). cAMP also engages exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC) (Rooij et al. 1998), influencing cell adhesion, cell-cell junctions, exocytosis/secretion, cell differentiation and proliferation, gene expression, apoptosis, and cardiac hypertrophy (Wang et al. 2017). Beyond enzymes, cAMP modulates ion flux by acting on cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels (Patra et al. 2023).

Because cAMP is used by many pathways, cells must control their signals in both time and space to preserve specificity. Spatial control comes from compartmentalization into multiprotein “signalosomes.” A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) tether PKA with selected effectors, phosphodiesterases (PDEs), and phosphatases to build microdomains or even smaller nanodomains at defined cellular sites. Within these domains, PKA phosphorylation activates nearby PDEs, which locally degrade cAMP and close a negative-feedback loop that terminates the signal (Yadav et al. 2025). Compartmentalization can be further reinforced by liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), the spontaneous condensation of biomolecules into reversible, membrane-less droplets. LLPS is governed by features such as intrinsically disordered regions and multivalency, by post-translational modifications, ligand/metabolite binding, local concentration, and the physicochemical environment (Folkmanaite et al. 2025). The quick assembly and disassembly of condensates at specific sites enables highly dynamic organization of signaling molecules. The spatial reach of a cAMP signal is ultimately set by phosphatase localization and activity, which define the functional boundary for PKA phosphorylation. Temporally, phosphatases reverse PKA phosphorylation to reset targets and limit the duration of cAMP effects (Conca et al. 2025).

cAMP and and oncology

The role of cAMP in cancer is intricate and often paradoxical. Its effects depend on genetic background, tumor type and stage, and microenvironmental influences. In many settings, increased cAMP-PKA/EPAC signaling promotes tumor growth, invasion, and therapy resistance (Zhang et al. 2024). Genetic alterations such as activating guanine nucleotide-binding protein alpha stimulating (GNAS) mutations or PKA fusion proteins (DNAJB1–PRKACA) drive persistent activation of this axis in gastrointestinal (Behmanesh et al. 2025) and liver cancers (Ahmed et al. 2022). PKA can regulate cytoskeletal dynamics (Howe 2004) and stress responses (Zhang et al. 2020). EPAC1 enhances adhesion, migration, glycolytic reprogramming, and metastasis in multiple cancer types. At the same time, EPAC activation has been shown to suppress migration in certain models (Zhang et al. 2024).

Downstream effector CREB integrates the signals at the transcriptional level and functions mainly as a tumor promoter (Ahmed et al. 2022). Its overexpression and hyperactivation are common in both solid and hematological malignancies, where it supports proliferation, angiogenesis, survival, and therapy resistance. High CREB activity is linked to poor prognosis and metastasis, and inhibition of CREB has been shown to reduce tumor growth and restore treatment sensitivity (Zhang et al. 2020).

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a decisive role in shaping cAMP responses. Low pH, a hallmark of the TME, stimulates proton-sensitive GPCRs that drive cAMP accumulation. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells can further modulate cAMP signaling through cytokine and growth factor release, while neuronal inputs via sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers add another regulatory layer. Together, these interactions promote angiogenesis, invasion, and immune evasion, including suppression of NK cell activity (Zhang et al. 2024).

cAMP and neurology

In the nervous system cAMP shapes how neurons grow, connect, and adapt. Boosting cAMP promotes neuronal survival and axon regrowth after spinal cord injury and shapes the activity of glial cells that support repair in the central nervous system (CNS) (Boczek et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2022).

cAMP is also essential for synaptic plasticity and circuit excitability. Globally, it enhances presynaptic neurotransmitter release, while locally it adjusts inhibitory synapses, striking a balance that allows efficient encoding of learning and memory (Lee 2015). In astrocytes, cAMP triggers glycogen breakdown and the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle, fueling neurons during high demand. This lactate not only supports excitability and long-term potentiation but also feeds back to regulate noradrenaline release, linking metabolism and neuromodulation. Antidepressants and monoamines further elevate astrocytic cAMP, leading to CREB-driven production of neurotrophic factors which support plasticity, neuroprotection, and mood regulation. Importantly, the timing and duration of cAMP signals matter: acute bursts and chronic elevations can produce opposite effects on astrocytic functions (Zhou et al. 2019).

Disruptions in cAMP signaling are recognized as a common thread across neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Variants in PKA or PDE4D disrupt synaptic signaling and have been linked to autism, Fragile X syndrome, and Alzheimer’s disease (Bhattacharya et al. 2025). Even sleep loss lowers hippocampal cAMP and weakens memory. Promisingly, new PDE4D inhibitors are being developed to restore cAMP balance and improve cognition (Bhattacharya et al. 2025).

Beyond the nervous system itself, cAMP-PKA signaling is now emerging as a key mediator of gut-brain communication. Microbial metabolites can tune host cAMP activity, activating vagal pathways and modulating immune and endocrine responses. In turn, altered cAMP signaling feeds back on microbiota composition, creating a reciprocal network that influences neurodevelopment, neurotransmitter control, and behavioral traits. This bidirectional regulation has direct relevance for amyloid-β aggregation, mitochondrial function, and microglial activation (Deng et al. 2025).

cAMP in immunity and inflammation

In the immune system, cAMP regulates both innate and adaptive cell activities and serves as a central checkpoint in inflammation. Elevating cAMP signaling typically produces anti-inflammatory effects, while reduced cAMP activity favors immune activation. In phagocytes such as monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils, cAMP dampens the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, restrains phagocytosis, and limits intracellular killing, thereby shaping the intensity of the inflammatory response (Raker et al. 2016).

cAMP is also a key mediator of resolution. It coordinates crosstalk with specialized pro-resolving mediators, regulates granulocyte recruitment, and fine-tunes apoptosis and clearance of dying cells. Importantly, cAMP drives macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory phenotypes, a hallmark of inflammation resolution (Tavares et al. 2020). When dysregulated, these processes contribute to chronic disease states; for instance, altered cAMP signaling influences both the onset and progression of ulcerative colitis (Cheng et al. 2024).

cAMP and 5P medicine

Modulation of cAMP pathways offers a powerful entry point for biomarker-driven interventions, directly aligning with the principles of 5P medicine. In oncology, expression of phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) and corresponding protein abundance have been identified as a predictive biomarker of chemotherapy response in hypopharyngeal cancer, underscoring the value of cAMP turnover in treatment stratification (Kawata-Shimamura et al. 2022). In neurodevelopmental disease, the selective PDE4D inhibitor BPN14770 (zatolmilast) has shown clinical benefit in Fragile X syndrome (Berry-Kravis, Gurney 2020). Chronic inflammatory diseases also illustrate this principle: in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inhibition of PDE4 superfamily members is integrated into precision strategies where biomarker data guide treatment decisions in defined patient subgroups (Bolger 2023). Together, these findings highlight how targeting cAMP signaling can move beyond experimental insight toward practical applications in precision and personalized therapeutics.

References

Ahmed, M. B. et al.: cAMP Signaling in Cancer: A PKA-CREB and EPAC-Centric Approach (2022) Cells | https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132020.

Barcelos, R. P. et al.: Caffeine effects on systemic metabolism, oxidative-inflammatory pathways, and exercise performance (2020) Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.) | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2020.05.005.

Berry-Kravis et al.: Positive Results Reported in Phase II Fragile X Clinical Trial of PDE4D Inhibitor Zatolmilast from Tetra Therapeutics (2020) | https://www.fraxa.org/positive-results-reported-in-phase-ii-fragile-x-clinical-trial-of-pde4d-inhibitor-from-tetra-therapeutics/

Behmanesh, M. A. et al.: Unraveling the link between GNAS R201 mutation and colorectal cancer (2025) Scientific Reports | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17399-y.

Bhattacharya, A. et al.: The promise of cyclic AMP modulation to restore cognitive function in neurodevelopmental disorders (2025) Current Opinion in Neurobiology | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2024.102966.

Boczek, T. et al.: Regulation of Neuronal Survival and Axon Growth by a Perinuclear cAMP Compartment (2019) Journal of Neuroscience | https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2752-18.2019.

Bolger, G. B.: Therapeutic Targets and Precision Medicine in COPD: Inflammation, Ion Channels, Both, or Neither? (2023) International Journal of Molecular Sciences | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417363.

Brimson, C. A. et al.: Collective oscillatory signaling in Dictyostelium discoideum acts as a developmental timer initiated by weak coupling of a noisy pulsatile signal (2025) Developmental cell | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2024.11.016.

Cheng, H. et al.: Cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate (cAMP) signaling is a crucial therapeutic target for ulcerative colitis (2024) Life Sciences | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122901.

Conca, F. et al.: Phosphatases Control the Duration and Range of cAMP/PKA Microdomains (2025) Function (Oxford, England) | https://doi.org/10.1093/function/zqaf007.

Deng, F. et al.: Exploring the interaction between the gut microbiota and cyclic adenosine monophosphate-protein kinase A signaling pathway: a potential therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases (2025) Neural Regeneration Research | https://doi.org/10.4103/NRR.NRR-D-24-00607.

Folkmanaite, M. et al.: Compartmentalisation in cAMP signalling: A phase separation perspective (2025) British Journal of Pharmacology | https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.70145.

Henkin, R. I. et al.: cAMP and cGMP in human parotid saliva: relationships to taste and smell dysfunction, gender, and age (2007) The American Journal of the Medical Sciences | https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3180de4d97.

Howe, A. K.: Regulation of actin-based cell migration by cAMP/PKA (2004) Biochimica et biophysica acta | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.005.

Jiang, L. I. et al.: Use of a cAMP BRET sensor to characterize a novel regulation of cAMP by the sphingosine 1-phosphate/G13 pathway (2007) The Journal of biological chemistry | https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M609695200.

Kawata-Shimamura, Y. et al.: Biomarker discovery for practice of precision medicine in hypopharyngeal cancer: a theranostic study on response prediction of the key therapeutic agents (2022) BMC Cancer | https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09853-1.

Kresge, N. et al.: Earl W. Sutherland’s Discovery of Cyclic Adenine Monophosphate and the Second Messenger System (2005) Journal of Biological Chemistry | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)48258-6.

Lee, D.: Global and local missions of cAMP signaling in neural plasticity, learning, and memory (2015) Frontiers in Pharmacology | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00161.

Oeckl, P. et al.: Simultaneous LC-MS/MS analysis of the biomarkers cAMP and cGMP in plasma, CSF and brain tissue (2012) Journal of Neuroscience Methods | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.09.032.

Patra, C. et al.: Biochemistry, cAMP (2023) | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535431/

Piec, I. et al.: A LC-MS/MS method for the diagnostic measurement of cAMP in plasma and urine (2017) | https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/65479/.

Raker, V. K. et al.: The cAMP Pathway as Therapeutic Target in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases (2016) Frontiers in Immunology | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00123.

Rooij, J. de et al.: Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP (1998) Nature | https://doi.org/10.1038/24884.

Tavares, L. P. et al.: Blame the signaling: Role of cAMP for the resolution of inflammation (2020) Pharmacological Research | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105030.

Wang, P. et al.: Exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (EPACs): Emerging therapeutic targets (2017) Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.065.

Yadav, R. et al.: GPCR signaling via cAMP nanodomains (2025) Biochemical Journal | https://doi.org/10.1042/BCJ20253088.

You, C. et al.: Coordination of bacterial proteome with metabolism by cyclic AMP signalling (2013) Nature | https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12446.

Zhang, H. et al.: Complex roles of cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling in cancer (2020) Experimental hematology & oncology | https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-020-00191-1.

Zhang, H. et al.: cAMP-PKA/EPAC signaling and cancer: the interplay in tumor microenvironment (2024) Journal of Hematology & Oncology | https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-024-01524-x.

Zhou, G. et al.: Multifaceted Roles of cAMP Signaling in the Repair Process of Spinal Cord Injury and Related Combination Treatments (2022) Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2022.808510.

Zhou, Z. et al.: The Astrocytic cAMP Pathway in Health and Disease (2019) International Journal of Molecular Sciences | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030779.