An update from the International Conference on the Bioscience of Lipids (ICBL 2025)

The International Conference on the Bioscience of Lipids (ICBL) 2025 in Innsbruck brought together leading researchers investigating lipid metabolism in health and disease. One session focused on peroxisomal lipid metabolism, emphasizing peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBDs) and demonstrating how disruptions in peroxisomal lipid processing contribute to clinical phenotypes – and how lipidomics provides critical insights into these mechanisms.

Peroxisomes were first linked to human disease in 1973, when Dr. Sidney Goldfischer observed that kidney and liver tissue from Zellweger syndrome (ZS) patients lacked these organelles (Goldfischer et al. 1973). The first biomarker for peroxisomal disorders was identified over 40 years ago (Moser et al. 1984), and the first gene defect over 30 years ago (Shimozawa et al. 1992). Before their biochemical basis was understood, the main peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBDs) – Zellweger spectrum syndrome (ZSS) and rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata (RCDP) – had already been described, representing the first malformation syndromes traced to metabolic errors (Steinberg et al. 2006).

Today, treatments remain largely supportive, targeting seizures, liver dysfunction, hearing, vision, and developmental needs. The recognition of milder, longer-living PBD patients has spurred renewed interest in experimental therapies, such as oral bile acid supplementation in ZS (Setchell et al. 1992), though plasmalogen precursor supplementation in RCDP has shown limited benefit (Steinberg et al. 2006; Das et al. 1992).

PEX genes in peroxisome biogenesis

Peroxisome formation begins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which delivers lipids and membrane proteins to form ER-derived pre-peroxisomal vesicles. These vesicles fuse to create nascent peroxisomes, giving them a lipid composition similar to the ER, enriched in phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) but lacking cardiolipins (Mast et al. 2020). Fusion also assembles the peroxisomal translocon, enabling import of soluble matrix proteins from the cytosol, which are essential for peroxisomal functions like lipid metabolism and reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulation. Peroxisomes then undergo fission and segregation to maintain a stable cellular population (Tabak et al. 2013; Mast et al. 2020).

Proper formation depends on peroxins, encoded by PEX genes, which control all stages of biogenesis, from protein import to division and turnover. Mutations in PEX genes disrupt peroxisome assembly, causing PBDs such as ZSS, characterized by metabolic dysfunctions including impaired very long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA) metabolism (Mast et al. 2020).

The sentinels of the cell

Peroxisomes are essential organelles in the cell, often referred to as “sentinels” due to their crucial role in maintaining lipid homeostasis and protecting cells from oxidative stress. Each peroxisome contains more than 50 enzymes involved in various metabolic pathways, with a particular emphasis on lipid metabolism. One of their key functions is the β-oxidation of VLCFAs (≥C22) (Mast et al. 2020). These fatty acids, both saturated and unsaturated, are exclusively degraded in the peroxisome. This process is essential not only for the metabolism of VLCFAs but also for the synthesis of bile acids and the inactivation of compounds such as prostaglandins (Steinberg et al. 2006). The peroxisomal breakdown of fatty acids contributes to the generation of metabolic intermediates that are used in other biosynthetic pathways, ensuring efficient lipid metabolism throughout the cell.

In addition to fatty acid degradation, peroxisomes are vital for the synthesis of plasmalogens. The first two steps of this ether phospholipid biosynthesis occur exclusively within peroxisomes. Plasmalogens comprise a significant fraction of membrane phospholipids in mammalian cells. For example, 80-90% of the ethanolamine phospholipids in myelin are plasmalogens, playing a critical role in maintaining membrane fluidity and structural integrity. Plasmalogens are also involved in protecting cells from oxidative damage, like antioxidants, helping to neutralize ROS (Brosche et al. 1998; Steinberg et al. 2006). Beyond this, plasmalogens are essential for various cellular processes such as membrane fusion, ion transport, and cholesterol efflux, all of which are crucial for maintaining cellular health and function, particularly in the brain and nervous system (Steinberg et al. 2006; Farooqui et al. 2001).

Beyond lipid metabolism, peroxisomes are involved in a wide array of other metabolic processes, including amino acid metabolism, glyoxylate metabolism, and bile acid metabolism (Steinberg et al. 2006), which are all integral to the overall metabolic flexibility of the cell. The peroxisomal involvement in bile acid synthesis is essential for the digestion and absorption of dietary lipids, further highlighting the organelle’s pivotal role in lipid metabolism (Steinberg et al. 2006). Through the enzyme catalase, peroxisomes also play a critical role in metabolizing hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), a byproduct of various cellular processes. This detoxification is essential for protecting cells, particularly those with high metabolic activity, from oxidative stress (Okumoto et al. 2020).

Interestingly, peroxisomal ROS production and regulation also play a significant role in cell signaling. The redox status of the cell can regulate various signaling pathways, particularly those involved in immune responses, stress adaptation, and inflammation. For instance, peroxisomal ROS can modulate the activity of redox-sensitive transcription factors such as NF-κB , which governs the expression of genes involved in inflammation and immune response (Fransen et al. 2012). Thus, peroxisomes not only act as the cell’s “sentinels” by controlling ROS but also influence key signaling pathways that govern cellular stress responses.

The spectrum of PBDs

PBDs are a group of heterogeneous autosomal recessive disorders caused by defects in the assembly of peroxisomes linked to PEX genes, leading to multiple enzyme deficiencies and a range of metabolic dysfunctions. Among the 16 PEX genes, mutations in 14 have been identified as causing PBDs (Braverman et al. 2013), and there are 13 known complementation groups associated with defects in specific PEX genes (Steinberg et al. 2006). PBDs are categorized into two broad types: Zellweger syndrome spectrum and rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata (RCDP), with ZS being the most severe disorder (Braverman et al. 2013).

PBDs present with a wide spectrum of symptoms, ranging from severe developmental abnormalities to milder manifestations. Peroxisomes are ubiquitous in the body, hence ZS affects nearly every organ system, causing craniofacial abnormalities (Steinberg et al. 2006), neurological degeneration, and retinal degeneration, which often results in childhood blindness (Omri et al. 2025). Other conditions in the ZS spectrum include neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy and infantile Refsum disease, which exhibit intermediate phenotypes (Braverman et al. 2013). RCDP is characterized by skeletal dysplasia and growth retardation (Steinberg et al. 2006). The diversity of phenotypes highlights the complex nature of these disorders, which involve both lipid metabolism dysfunction and peroxisomal enzyme deficiencies.

The pathophysiology of ZS is largely due to defects in peroxisomal function, leading to disrupted lipid metabolism. Key issues include the accumulation of VLCFAs and plasmalogen deficiency, both of which are critical for maintaining membrane integrity and protecting cells from oxidative stress. In ZS, the brain accumulates VLCFAs and cholesterol esters. Additionally, the brain of ZS patients shows excessive polyunsaturated fatty acids (>C32), which are predominantly found in PCs . This accumulation of lipids plays a key role in pathogenesis, particularly in neuronal function and neurodegeneration (Steinberg et al. 2006). The depletion of plasmalogens further exacerbates membrane instability, leading to the functional decline of neurons and photoreceptors (Omri et al. 2025).

RCDP is caused by mutations in the PEX7 gene, coding for peroxin-7, which is crucial for the peroxisomal import of matrix proteins. Plasmalogen biosynthesis is impaired, leading to deficient plasmalogen levels in tissues such as the brain, liver, and muscle, while VLCFAs remain normal. The deficiency in plasmalogen synthesis is especially severe in RCDP and is linked to skeletal dysplasia (Steinberg et al. 2006; Bams-Mengerink et al. 2006).

The diagnostic approach for PBDs relies on measuring VLCFA levels and plasmalogen content, along with PEX gene sequencing to identify the specific mutations involved (Steinberg et al. 2006). Despite long-standing efforts, researchers are still busy unravelling the metabolic and cellular mechanisms underlying the clinical phenotypes.

The metabolic disruptions at the root of clinical symptoms

Understanding how genetic defects in PEX genes translate into metabolic disruptions is central to deciphering the clinical manifestations of PBDs. One of the most studied models is the PEX1-G844D knock-in mouse, which represents the common human PEX1-c.2528G>A allele (encoding PEX1-G843D). This model exhibits features of milder ZSS, including retinal degeneration (Hiebler et al. 2014).

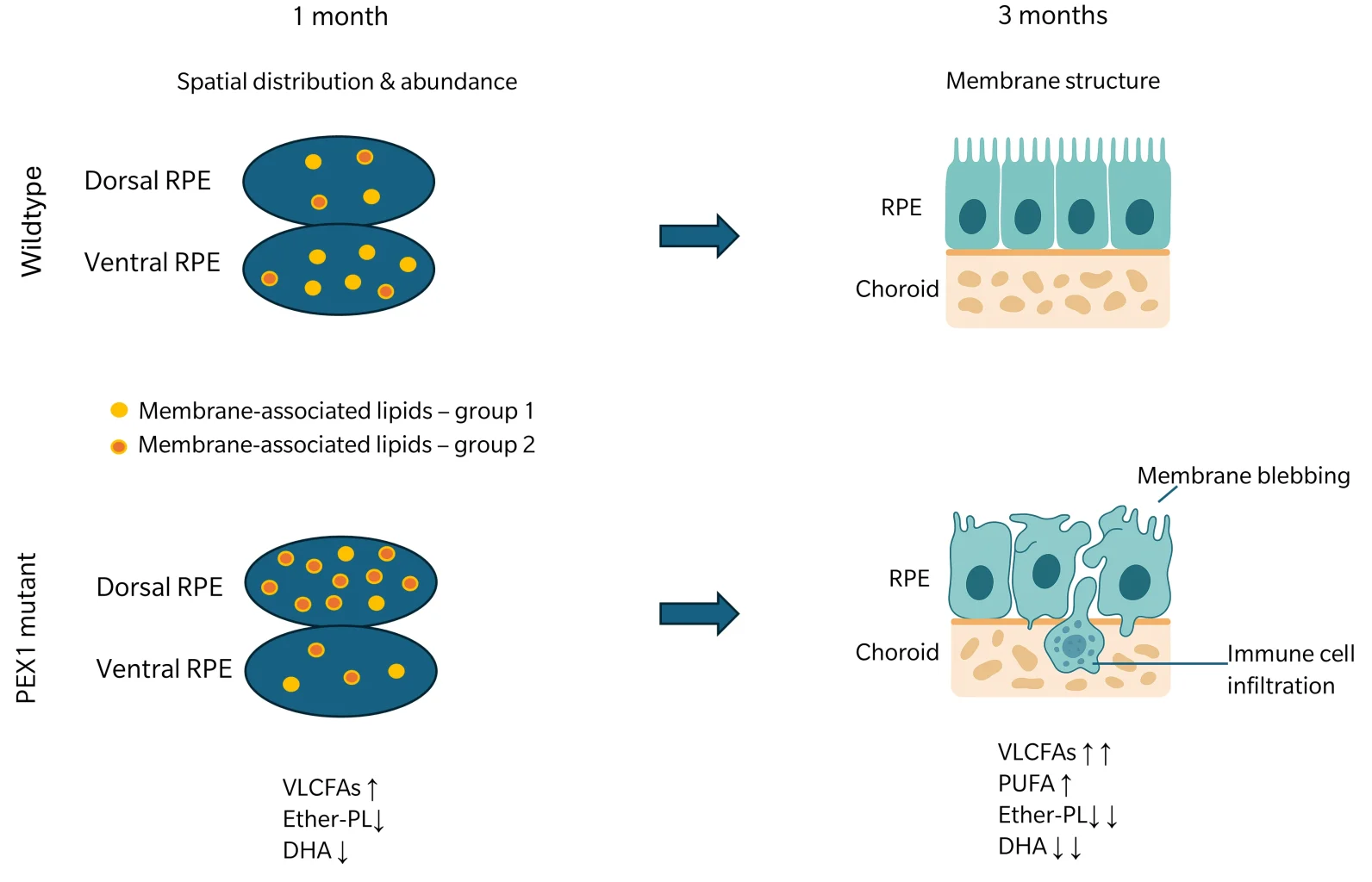

In this model, one month after birth, PEX1-G844D retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tissues already showed altered lipid composition, which can disrupt membrane fluidity and impair the function of membrane-bound proteins critical for nutrient transport, waste removal, and the visual cycle. A set of membrane-associated lipids was dysregulated, with PCs , phosphatidylinositols (PIs) and sphingomyelin (SM) species abnormally distributed between dorsal and ventral poles. Additionally, there was a significant increase in VLCFAs and a reduction in plasmalogens and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-containing lipids, highlighting disrupted peroxisomal lipid metabolism (Omri et al. 2025). These early lipid disturbances likely contribute to disrupted RPE membrane trafficking critical for photoreceptor support (Storm et al. 2020) and set the stage for progressive retinal degeneration.

Figure 2: Abundance and spatial distribution of membrane-associated lipids in WT or PEX1 mutant tissue at 1 month of age. Group 1: Lipids that are distributed heterogeneously in WT, with higher abundance at the ventral pole. Group 2: Lipids with altered lipid patterns in mutants compared to the WT and higher abundance in the dorsal pole. The lipid pattern of mutants is characterized by increased levels of VLCFAs along with decreased plasmalogens and DHA-associated lipids. At 3 months of age, tissue of mutants show structural aberrations, including membrane blebs and immune cell infiltration. The lipid pattern shown at 1 month of age is further intensified with an additional trend toward increasing PUFAs. Figure is based on findings from Omri et al. 2025.

By three months, structural abnormalities featured enlarged, disorganized RPE cells and plasma membrane blebbing, indicative of cellular stress (Martins et al. 2024). This was accompanied by subretinal inflammation, with infiltration of immune cells absent in control tissues. Spatial lipidomic analysis showed a trend toward increased polyunsaturated fatty acids, along with persistent decreases in DHA-containing lipids and further accumulation of VLCFAs. These findings suggest that early lipid remodeling precedes both inflammation and structural damage, potentially serving as a predictive marker of retinal degeneration. The initial accumulation of dysregulated lipids in the dorsal pole, followed by a more generalized spread, indicates that these lipid changes may initiate or drive the progression of tissue damage (Omri et al. 2025).

Building on these findings, unpublished data from PEX16-deficient mice presented at ICBL 2025 by Braverman and colleagues suggest a similar sequence of events. In these hypomorphic PEX16 models, mice exhibited reduced PEX16 transcript and protein and abnormal peroxisomal metabolites across multiple tissues. The earliest detectable changes were in lipid patterns, which were subsequently followed by structural alterations, mirroring the sequence observed in the retina of PEX1-G844D mice. In addition, there was increased infiltration of hematopoietic stem cells and early inflammatory responses in both brain and eyes, features not commonly seen in ZSD patients. Together, these findings support the notion that peroxisomal lipid dysregulation triggers oxidative stress and inflammation, which act as central drivers of clinical phenotypes, including neurodegeneration and retinal damage.

Using targeted lipidomics to decipher disease mechanisms

Targeted lipidomics using the biocrates MxP® Quant 1000 kit enables precise quantification of more than 40 free fatty acids and 906 complex lipids from 25 biochemical classes, assessing VLCFAs, plasmalogens, and DHA-containing lipids. With up to 325 lipid-based metabolite sums and ratios, this approach allows researchers to detect early lipid changes before structural damage occurs, map region-specific alterations, and correlate them with oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular dysfunction. The kit also covers amino acid metabolism, glyoxylate metabolism, and bile acid metabolism, and is thus an excellent fit for holistic studies of metabolic effects of peroxisomal diseases. By providing reproducible, quantitative data, targeted lipidomics helps identifying biomarkers of disease progression, understanding mechanistic links between mutations and clinical phenotypes, and evaluating the impact of potential therapies in both preclinical models and patient samples.

References

Bams-Mengerink, A. M. et al.: MRI of the brain and cervical spinal cord in rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata (2006) Neurology | https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000205594.34647.d0.

Braverman, N. E. et al.: Peroxisome biogenesis disorders: Biological, clinical and pathophysiological perspectives (2013) Develop mental Disabilities Research Reviews | https://doi.org/10.1002/ddrr.1113.

Brosche, T. et al.: The biological significance of plasmalogens in defense against oxidative damage (1998) Experimental Gerontology | https://doi.org/10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00014-x.

Das, A. K. et al.: Dietary ether lipid incorporation into tissue plasmalogens of humans and rodents (1992) Lipids | https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02536379.

Farooqui, A. A. et al.: Plasmalogens: workhorse lipids of membranes in normal and injured neurons and glia (2001) The Neuroscientist | https://doi.org/10.1177/107385840100700308.

Fransen, M. et al.: Role of peroxisomes in ROS/RNS-metabolism: implications for human disease (2012) Biochimica et biophysica acta | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.001.

Goldfischer, S. et al.: Peroxisomal and mitochondrial defects in the cerebro-hepato-renal syndrome (1973) Science (New York, N.Y.) | https://doi.org/10.1126/science.182.4107.62.

Hiebler, S. et al.: The Pex1-G844D mouse: a model for mild human Zellweger spectrum disorder (2014) Molecular genetics and metabolism | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.01.008.

Martins, B. et al.: Contribution of extracellular vesicles for the pathogenesis of retinal diseases: shedding light on blood-retinal barrier dysfunction (2024) Journal of biomedical science | https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-024-01036-3.

Mast, F. D. et al.: Peroxisome prognostications: Exploring the birth, life, and death of an organelle (2020) Journal of Cell Biology | https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201912100.

Moser, A. E. et al.: The cerebrohepatorenal (Zellweger) syndrome. Increased levels and impaired degradation of very-long-chain fatty acids and their use in prenatal diagnosis (1984) The New England journal of medicine | https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198405033101802.

Okumoto, K. et al.: The peroxisome counteracts oxidative stresses by suppressing catalase import via Pex14 phosphorylation (2020) eLife | https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.55896.

Omri, S. et al.: Spatial characterization of RPE structure and lipids in the PEX1-p.Gly844Asp mouse model for Zellweger spectrum disorder (2025) Journal of lipid research | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlr.2025.100771.

Setchell, K. D. et al.: Oral bile acid treatment and the patient with Zellweger syndrome (1992) Hepatology | https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840150206.

Shimozawa, N. et al.: A human gene responsible for Zellweger syndrome that affects peroxisome assembly (1992) Science (New York, N.Y.) | https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1546315.

Steinberg, S. J. et al.: Peroxisome biogenesis disorders (2006) Biochimica et biophysica acta | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.010.

Storm, T. et al.: Membrane trafficking in the retinal pigment epithelium at a glance (2020) Journal of cell science | https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.238279.

Tabak, H. F. et al.: Peroxisome formation and maintenance are dependent on the endoplasmic reticulum (2013) Annual Review of Biochemistry | https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-081111-125123.