- History & Evolution

- Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

- Indoxyl sulfate and the microbiome

- Indoxyl sulfate and nephrology

- Indoxyl sulfate and cardiovascular disease

- Indoxyl sulfate and bone disease

- Indoxyl sulfate and neurological disease

History & Evolution

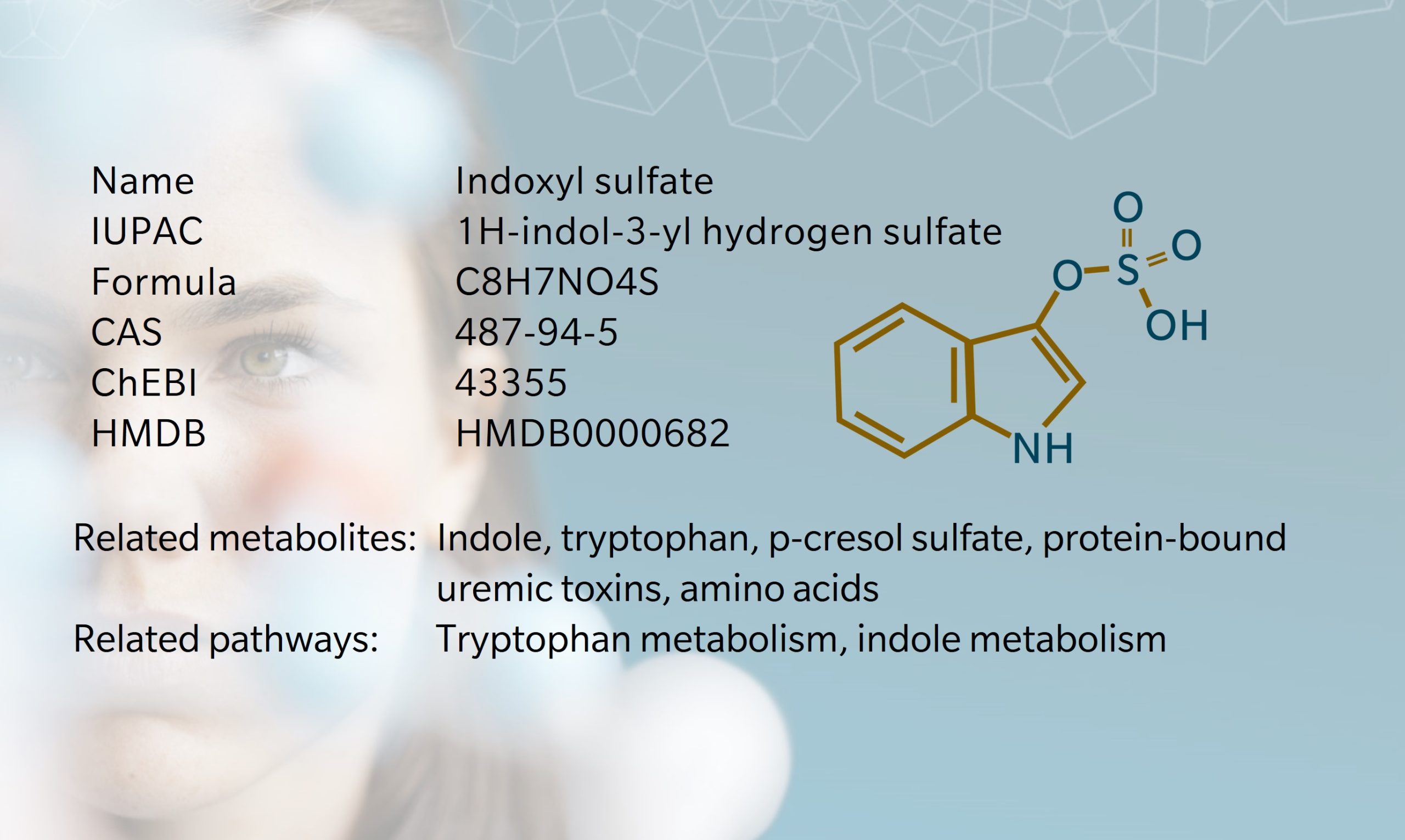

1911: discovery of indoxyl sulfate (Obermayer, F. and Popper, H., 1911) | 1936: confirmation of liver’s role in indoxyl sulfate production (Houssay, B., 1936) | 1950s: discovery of role in kidney disease (Leong, S. and Sirich, T., 2016).

In 1911, Obermayer and Popper discovered high concentrations of a metabolite, then called “indican,” in patients with kidney disease (Obermayer, F. and Popper, H., 1911). Indoxyl sulfate, as it later came to be known, was initially studied as a “putrefaction” product of intestinal microbial metabolism. In the 1950s, researchers explored whether urinary excretion of indoxyl sulfate might indicate various diseases, eventually focusing on its role in kidney disease. This was a major leap forwards in understanding uremia, which had puzzled scientists for decades (Leong, S. and Sirich, T., 2016).

As a key uremic toxin, accumulation of indoxyl sulfate affects the kidneys, cardiovascular system and bones (Colombo, G. et al., 2022). Indoxyl sulfate has been linked to cognitive impairment, oxidative stress and blood-brain barrier permeability, and is also thought to play a role in remote sensing and signaling in renal and extra-renal tissues (Lowenstein, J. and Nigam, S., 2021). Recent research has focused on IS as a potential therapeutic target in chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, especially when these conditions are comorbid.

Indoxyl sulfate is a precursor of indigo, which has been used as a dye for thousands of years. This connection is illustrated vividly in “purple urine bag syndrome,” where constipation or urinary tract infections cause an accumulation of bacteria in urine collection bags, leading to the conversion of indoxyl sulfate into indigo and indirubin, and resulting in purple urine (Tan, C. et al., 2008).

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

Indoxyl sulfate is produced from precursors synthesized via the tryptophan-indole pathway in the gut (Banoglu, E. et al., 2001). In the first step, L-tryptophan, an amino acid obtained from dietary protein, is metabolized by tryptophanase-expressing bacteria in the intestine to produce indole. Indole is absorbed into the bloodstream and is converted to indoxyl in the liver via hydroxylation by cytochrome enzymes including CYP2E1. Sulfotransferase enzymes in the liver complete the process by converting indoxyl into indoxyl sulfate.

Research suggests that increasing dietary tryptophan (typically found in protein-rich foods) may increase indoxyl sulfate production (Lauriola, M. et al., 2023; Leong, S. and Sirich, T., 2016). I ndividuals following high-protein diets show higher levels of indoxyl sulfate in both plasma and urine compared to those on low-protein or vegetarian diets (Patel, K. et al., 2012). Conversely, very low protein diets have been shown to reduce indoxyl sulfate levels (Marzocco, S. et al., 2013). A study of 56 hemodialysis patients found that increasing dietary fiber also reduced indoxyl sulfate levels (Sirich, T. et al., 2014).

In healthy individuals, the indoxyl sulfate concentrations range is10-130 mg/day, clearing rapidly through the kidneys (Patel, K. et al., 2012). Kidney dysfunction inhibits clearing, causing indoxyl sulfate to accumulate, which contributes to renal and cardiovascular toxicity as discussed below (Hung, S. et al., 2017). The full extent of IS’ role in healthy phenotypes remains to be discovered.

Indoxyl sulfate and the microbiome

More than 85 species of bacteria produce indole through the action of tryptophanase on tryptophan (Melander, R. et al., 2014). Tryptophanase has been found in bacteria including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium longum, Bacteroides fragilis, Parabacteroides distasonis, Clostridium bartlettii and E. hallii (Zhang, L. and Davies, S., 2016). Even more species respond to the presence of indole, despite lacking tryptophanase and thus not producing indole themselves.

The role of the liver in indoxyl sulfate production was known as far back as 1936, when animal studies revealed that indoxyl sulfate could be produced even in the absence of a digestive tract, as long as the liver was intact (Houssay, B., 1936). More recently, metabolomics has confirmed the involvement of the gut microbiome in indoxyl sulfate production: studies comparing indoxyl sulfate levels in conventional and germ-free rats, and in hemodialysis patients with and without colons, highlight the significant role of colon bacteria (Leong, S. and Sirich, T., 2016).

Indoxyl sulfate and nephrology

As a uremic toxin, indoxyl sulfate is strongly implicated in the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Caggiano, G. et al., 2023). As renal function declines, indoxyl sulfate concentrations rise, making it a useful biomarker of CKD. Both indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol sulfate, another protein-bound uremic toxin, are linked to symptoms of renal disease such as inflammation and fibrosis (Caggiano, G. et al., 2023). Indoxyl sulfate levels increase progressively with each stage of CKD (Clark, W. et al., 2019). Patients with hospital-acquired acute kidney injury have also been found to have higher serum levels of indoxyl sulfate (Menez, S. et al., 2019). Hemodialysis is limited in its ability to remove plasma protein bond, and dialysis patients with end-stage renal disease have been found to have indoxyl sulfate levels more than 20 times higher than those of healthy subjects (Wang, Y. et al., 2020).

Emerging evidence suggests that interventions that reduce indoxyl sulfate levels may slow CKD progression, though results remain inconclusive (Wang, Y. et al., 2020). Generally, there appears to be a good indication that administering prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics can reduce indoxyl sulfate in patients with CKD and renal failure, although further research is needed (Lim, Y. et al., 2021).

Administration of AST-120 seems to be particularly promising for CKD (Lim, Y. et al., 2021). This treatment works by adsorbing indole and p-cresol to minimize downstream indoxyl sulfate production. AST-120 has been shown to slow the decline in glomerular filtration rate of CKD patients in some clinical studies, although randomized controlled trials have been inconclusive. More research is needed to determine whether gut microbiome modulation is a viable strategy in kidney disease.

Indoxyl sulfate and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is higher among patients with CKD than the general population. While this relationship is not entirely understood, uremic toxins are thought to play a role, acting as vascular toxins as they accumulate in the blood (Barreto, F. et al., 2009; Zhao, Y. and Wang, Z., 2020). IS disrupts endothelial integrity and is linked to pro-oxidant, pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic processes, contributing to atherosclerosis, aortic calcification and vascular disease (Lano, G. et al., 2020). Indoxyl sulfateis also an agonist for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) on vascular smooth muscle cells, further promoting the formation of atherosclerotic lesions and thrombosis (Leong, S. and Sirich, T., 2016). These mechanisms highlight indoxyl sulfate as a key player in the progression of cardiovascular complications in CKD.

Metabolomics studies have provided further insight into the role of indoxyl sulfate in cardiovascular health. For example, research shows that elevated indoxyl sulfate in plasma predicts cardiovascular events in patients with congestive heart failure and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Imazu, M. et al., 2020). Another study showed an association between plasma indoxyl sulfate levels and arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes (Katakami, N. et al., 2020). Diabetes can disrupt gut microbial composition and metabolism, which may contribute to increased indoxyl sulfate levels.

Indoxyl sulfate and bone disease

Patients with CKD often develop mineral bone disorders (CKD-MBD). Research suggests a link between this disorder and IS, though the precise mechanism is unclear (Liu, W. et al., 2018). One possibility is that the accumulation of uremic toxins weakens bone quality and quantity, potentially leading to uremic osteoporosis. Bone responses to parathyroid hormone (PTH) are also progressively lower in CKD patients, with studies suggesting a connection between PTH resistance, low bone turnover and increased indoxyl sulfate levels. Furthermore, indoxyl sulfate acts on AhR and activates signaling pathways that can induce ferroptosis and disrupt osteoblast differentiation (Chen, H. et al., 2024). Uremic toxin adsorbents may be a potential therapeutic strategy to improve bone health in patients with renal disease.

Indoxyl sulfate and neurological disease

A relatively new area of interest is the link between indoxyl sulfate and neurology, particularly its involvement in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, anxiety and other neurological disorders. In CKD patients, accumulation of uremic toxins can lead to cerebrovascular lesions, increasing the risk of cognitive disorders and dementia (Sankowski, B. et al., 2020).

Using metabolomics, Sankowski et al. demonstrated that patients with Parkinson’s disease had higher levels of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol sulfate in cerebrospinal fluid compared to controls, and higher levels of another uremic toxin, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), in plasma (Sankowski, B. et al., 2020).

Another metabolomics study quantified molecular markers in whole blood of dementia patients, and found elevated levels of indoxyl sulfate compared to healthy controls, again suggesting that indoxyl sulfate may be neurotoxic (Teruya, T. et al., 2021).

Indoxyl sulfate levels also positively correlate with severity of anxiety, according to an exploratory metabolomics study (Brydges, C. et al., 2021). While modulating indole levels did not seem to affect treatment outcomes, the fact that a gut microbiome-derived metabolite influenced neural processing provides further evidence of a link between the gut microbiome and neuropsychiatric disorders.

References

Banoglu, E. et al.: Hepatic microsomal metabolism of indole to indoxyl, a precursor of indoxyl sulfate. (2001). Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet | DOI: 10.1007/BF03226377.

Barreto, F. et al.: Serum Indoxyl Sulfate Is Associated with Vascular Disease and Mortality in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. (2009) Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology | DOI:10.2215/CJN.03980609.

Caggiano, G. et al.. Gut-Derived Uremic Toxins in CKD: An Improved Approach for the Evaluation of Serum Indoxyl Sulfate in Clinical Practice (2023) Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(6) | DOI:10.3390/ijms24065142.

Chen, H. et al.: Indoxyl sulfate exacerbates alveolar bone loss in chronic kidney disease through ferroptosis (2024) Oral Dis.| DOI:10.1111/odi.15050.

Clark, W. et al.: Uremic Toxins and their Relation to Dialysis Efficacy (2019) Blood Purif., 48(4) | DOI:10.1159/000502331.

Colombo, G. et al.: Effects of the uremic toxin indoxyl sulphate on human microvascular endothelial cells (2022) J Appl Toxicol., 42(12) | DOI:10.1002/jat.4366.

Houssay, B.: Phenolemia and Indoxylemia: Their Origin, Significance, and Regulation. (1936) Am. J. Med. Sci., 192, 615–626 https://shorturl.at/e4GsH

Hung, S. et al.: Indoxyl Sulfate: A Novel Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease (2017) J Am Heart Assoc., 6(2) | DOI:10.1161/JAHA.116.005022.

Imazu, M. et al.: Plasma indoxyl sulfate levels predict cardiovascular events in patients with mild chronic heart failure (2020). Scientific Reports, 10 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-73633-9.

Katakami, N. et al.: Plasma metabolites associated with arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes (2020) Cardiovasc Diabetol., 19(75) | DOI:10.1186/s12933-020-01057-w.

Lano, G. et al.: Indoxyl Sulfate, a Uremic Endotheliotoxin (2020) Toxins (Basel), 12(4), 229 | DOI:10.3390/toxins12040229.

Lauriola, M. et al.: Food-Derived Uremic Toxins in Chronic Kidney Disease (2023) Toxins (Basel), 12(2), 116 | DOI:10.3390/toxins15020116.

Leong, S. and Sirich, T: Indoxyl Sulfate—Review of Toxicity and Therapeutic Strategies (2016) Toxins (Basel), 8(12), 358 | DOI:10.3390/toxins8120358.

Lim, Y. et al.: Uremic Toxins in the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease and Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets (2021) Toxins, 13(2), 142 | DOI:10.3390/toxins13020142.

Liu, W. et al.: Effect of uremic toxin-indoxyl sulfate on the skeletal system. (2018) Clinica Chimica Acta, 484, 197-206. | DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2018.05.057.

Lowenstein, J. and Nigam, S.: Uremic Toxins in Organ Crosstalk (2021) Front Med (Lausanne), 8, 592602. | DOI:10.3389/fmed.2021.592602.

Marzocco, S. et al.: Very low protein diet reduces indoxyl sulfate levels in chronic kidney disease (2013) Blood Purif., 35(1-3), 196-201 | DOI:10.1159/000346628.

Melander, R. et al.: Controlling bacterial behavior with indole-containing natural products and derivatives (2014)Tetrahedron, 70(37), 6363–6372 | DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2014.05.089.

Menez, S. et al.: Indoxyl sulfate is associated with mortality after AKI – more evidence needed! (2019) BMC Nephrol., 20(1), 280 | DOI:10.1186/s12882-019-1465-0.

Obermayer, F. and Popper, H. Ueber Urämie (1911) Ztschr. f. klin. Med., 72, 332-372.

Patel, K. et al.: The Production of p-Cresol Sulfate and Indoxyl Sulfate in Vegetarians Versus Omnivores (2012) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol., 7(6), 982–988 | DOI:10.2215/CJN.12491211.

Sankowski, B. et al.: Higher cerebrospinal fluid to plasma ratio of p-cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate in patients with Parkinson’s disease (2020) Clinica Chimica Acta, 501, 165-173 | DOI: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.10.038.

Sirich, T. et al.: Effect of Increasing Dietary Fiber on Plasma Levels of Colon-Derived Solutes in Hemodialysis Patients(2014) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol., 9(9), 1603–1610 | DOI:10.2215/CJN.00490114.

Tan, C. et al.: Purple urine bag syndrome (2008) CMAJ, 179(5), 491| DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.071604.

Teruya, et al.: Whole-blood metabolomics of dementia patients reveal classes of disease-linked metabolites (2021) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(37) | DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2022857118

Wang, Y. et al.: Targeting the gut microbial metabolic pathway with small molecules decreases uremic toxin production (2020) Gut Microbes, 12(1) | DOI: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1823800.

Zhang, L. and Davies, S.: Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions(2016) Genome Med., 8(46) | DOI: 10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x.

Zhao, Y. and Wang, Z.: Gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease(2020) Curr Opin Cardiol., 35(3), 207–218 | DOI: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000720.