History & Evolution

1853: discovery (Liebig et al. 1853) | 1904: first synthesized from tryptophan (Ellinger et al. 1904) | 1980s: mode of action discovered

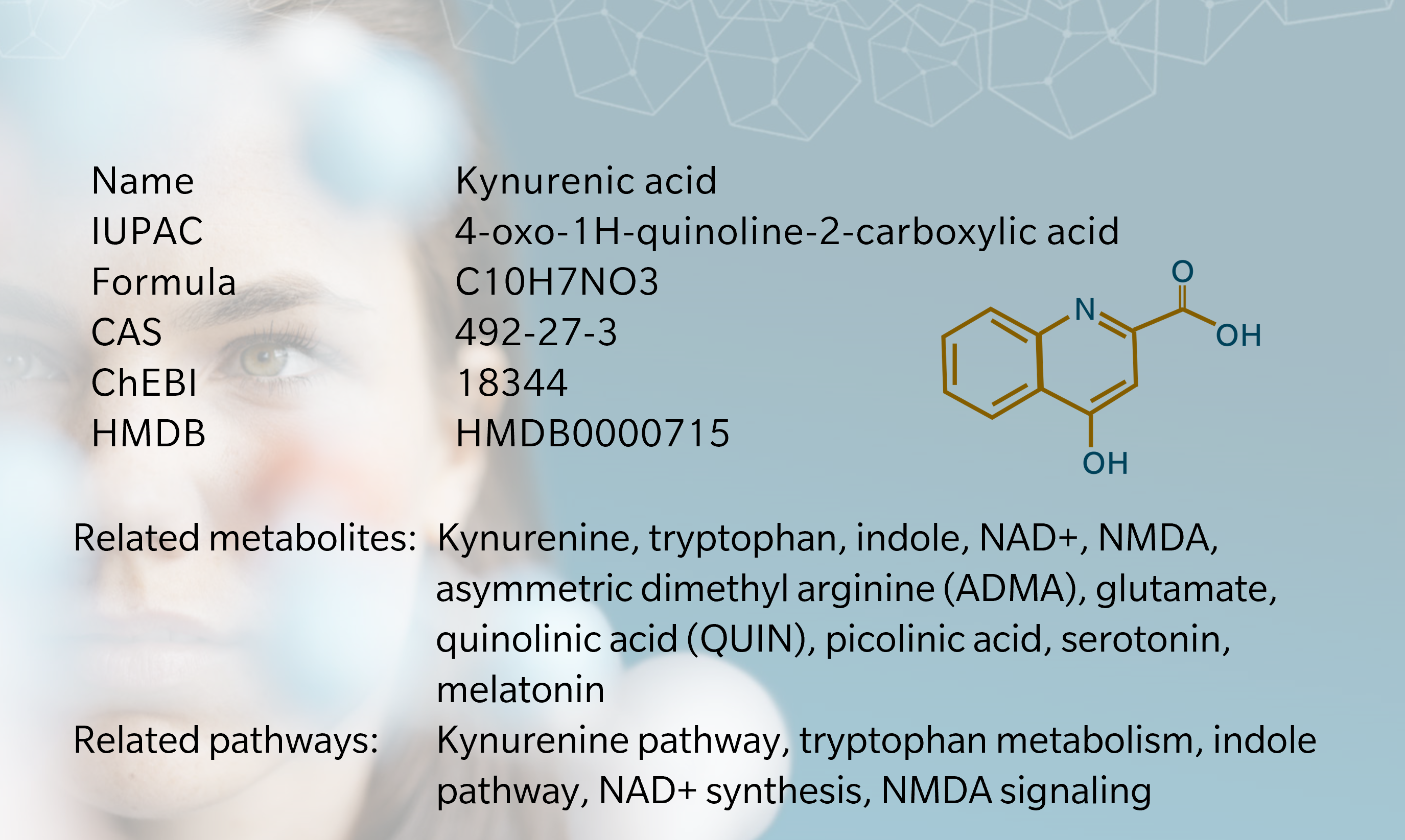

Kynurenic acid (KYNA) was first discovered in 1853 by German chemist Justus von Liebig in dog urine, which inspired its name (Liebig 1853). Fifty years later, another German chemist, Ellinger, identified it as one of the first metabolites isolated from tryptophan, again from dog urine (Ellinger 1904). Initially considered little more than a by-product of the more interesting kynurenine, KYNA caught the attention of researchers investigating the brain and central nervous system (CNS) in the 1980s and 90s, when it was identified as an antagonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors (Turski et al. 2013).

KYNA is found in several mammalian organs and tissues, including the brain, retina, liver, kidneys, intestines, cardiac muscles and bodily fluids, including breast milk (Turska et al. 2022). It is also found in plants, although its role in plant physiology remains largely unexplored (Wróbel-Kwiatkowska et al. 2024).

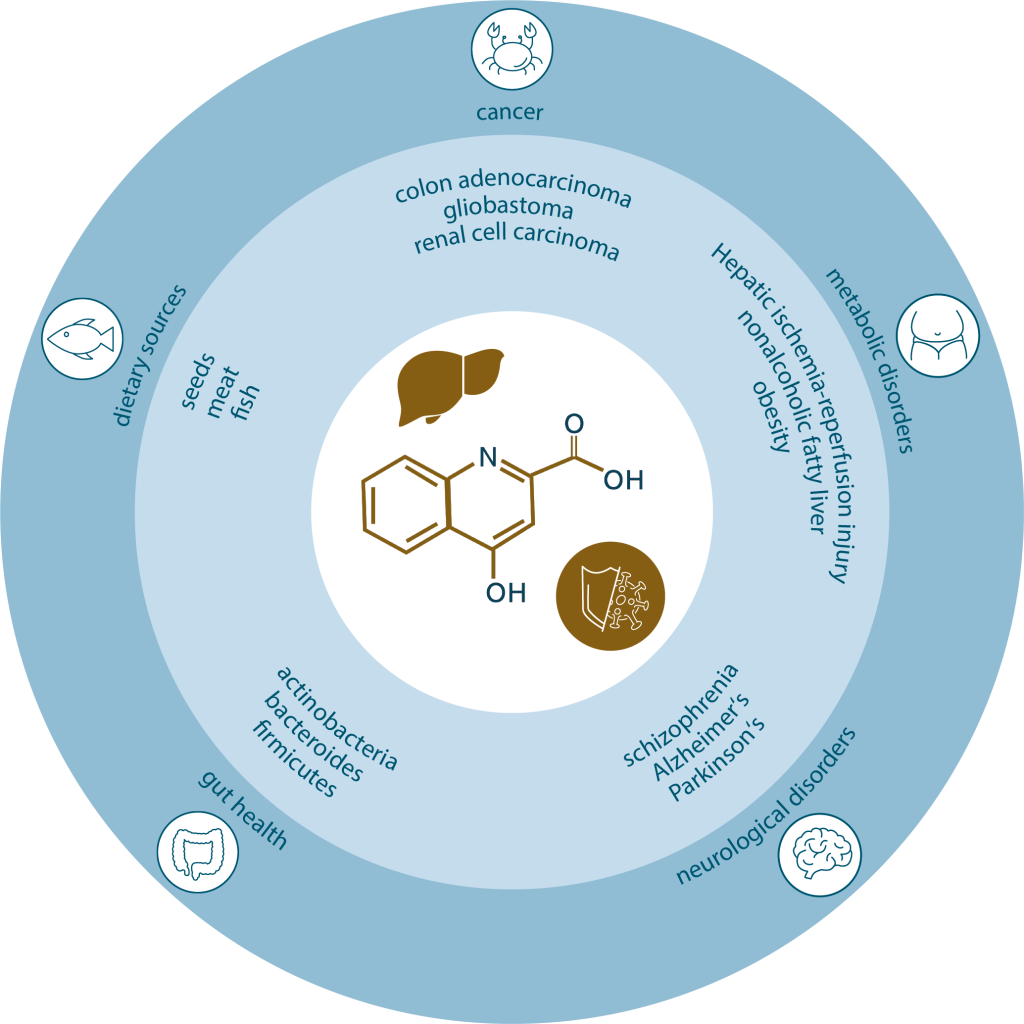

KYNA is associated with a wealth of health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. Its well-established role in neurotransmission systems links it to several neurological and cognitive conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), schizophrenia and mood disorders (Zhen et al. 2022). More recent evidence points to a role in energy homeostasis and in the immune and digestive systems, and it is also emerging as a potential biomarker of metabolic disease and endocrine disease (Zhen et al. 2022).

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

KYNA is primarily synthesized intracellularly via the kynurenine pathway. While this process occurs endogenously, it relies on tryptophan, an exogenous essential amino acid that must be obtained through diet (Friedman et al. 2018). Dietary sources of tryptophan include seeds, soybeans, dairy, meat, fish, eggs and legumes. KYNA itself is usually found in quite low concentrations in food, with the exception of honey, broccoli and potatoes (Turski et al. 2009).

The kynurenine pathway metabolizes more than 90% of dietary tryptophan in the liver to form kynurenine, KYNA, quinolinic acid (QUIN) and other metabolites (Hou et al. 2023, Stone et al. 2013). In humans, kynurenine is primarily synthesized endogenously from tryptophan. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) in the liver and, to a lesser extent, by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in other organs including immune cells (Savitz et al. 2020). Alternative mechanisms that may influence KYNA production in the brain involve D-amino acids, D-amino acid oxidase, and the effects of free radicals (Ramos-Chávez et al. 2018).

KYNA is synthesized in the gut microbiome, absorbed through the lumen of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and transported to the liver, kidneys and other organs via the bloodstream (Turska et al. 2022). Concentration levels in digestive fluids increase steadily following ingestion, with blood levels peaking at around 15-30 minutes following ingestion (Sadok et al. 2023). Any that is not absorbed is excreted in urine.

Kynurenic acid and the microbiome

In the GI tract, tryptophan metabolism is modulated by gut microbiota including the bacterial phyla Actinobacteria, Bacteroides, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria (Dehhaghi et al. 2020). Gut microbiota can influence the kynurenine pathway by regulating IDO-1 activity or tryptophan availability (Dehhaghi et al. 2019). For example, administering Bifidobacterium infantis to germ-free mice has been shown to increase KYNA levels (Desbonnet et al. 2008). Similarly, IDO and TDO have been found to reduce the kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio in germ-free animals, but when those animals were exposed to microbiota, the enzyme activity normalized (Cryan et al. 2012).

The production of kynurenine metabolites is known to affect host physiology, with multiple studies demonstrating how manipulating microbial populations influences the kynurenine pathway and neural, endocrine and immune pathways (Cryan et al. 2012) (Dehhaghi et al. 2019). Differences in gut microbiota of healthy individuals and those with clinical conditions have been observed in diseases associated with the kynurenine pathway, such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, AD, PD, multiple sclerosis, ASD and irritable bowel syndrome (Purton et al. 2021).

There is still much to learn about the role of specific bacteria in producing KYNA and related therapeutic possibilities (Dehhaghi et al. 2019). A 2021 systematic review by Purton et al. showed that probiotics could modulate metabolite activity in the kynurenine pathway. However, evidence regarding the effect of prebiotics on this pathway remains limited (Purton et al. 2021).

Find out more about neurometabolomics, an evolving approach to better understand the role of KYNA and other metabolites in brain processes and function.

Kynurenic acid receptors

KYNA is a ligand to several receptors, acting as a signaling molecule for multiple physiological processes:

• It is an antagonist of the three ionotropic glutamate receptors N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and kainite, which mediate its effects in the brain (Schwarcz, R. et al. 2012). This makes it a useful test for glutamate involvement in synaptic transmission, for example in cases of stroke (Stone et al. 2000).

• KYNA is also thought to be an antagonist of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) (Albuquerque et al. 2013). However, this hypothesis is controversial: the results of studies showing that KYNA blocks NMDA receptors but not nicotinic receptors have not been consistently reproducible, while investigations using KYNA analogs may be vulnerable to misinterpretation (Stone et al. 2020). Given the role of α7nAChR in CNS disorders, there’s a strong case for more research to better understand if and how KYNA may block its action.

• KYNA has been more assuredly identified as an agonist of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) GPR35, which is primarily present in the GI tract (Turski et al. 2013). Research in this area has led to the suggestion that KYNA could have a mediating effect on GI disorders, including ulcers, colitis and colon obstruction. KYNA’s role in modulating GPR35 also links it to immune system regulation, as does its role as an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (Tsuji et al. 2023). In 2020, researchers using DCyFIR, a CRISPR-based GPCR screening platform for ligand and drug discovery, found that KYNA activates hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor (HCAR3) in addition to GPR35 (Kapolka et al. 2020).

Because of its varied signaling effects on the immune system, inflammation, neuropathology, cancer and gut homeostasis, KYNA has been described as a “double-edged sword” (Wirthgen et al. 2017). Its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive functions are beneficial in some respects, but elevated levels of circulating KYNA are also associated with several diseases, as discussed below.

Interestingly, there appears to be a sex-specific association between circulating KYNA and immune response: a study using untargeted metabolomics found that male patients with COVID-19 had higher levels of KYNA than females, correlating with age, inflammation and disease severity (Cai et al. 2021). This may explain a potential link between KYNA levels and the differing outcomes in men and women with COVID-19.

Kynurenic acid and neurology

KYNA levels are altered in various mental disorders, with decreased levels observed in patients with affective psychosis, chronic schizophrenia, AD, cluster headaches, and chronic migraines (Wirthgen et al. 2017). Patients with PD show increased ratios of KYNA and KYNA/kynurenine, along with lower ratios of QUIN and QUIN/KYNA (Chang et al. 2018). Elevated KYNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenia patients and its correlation with inflammatory biomarkers in AD suggest a link between KYNA and neuroinflammation (Wennström et al. 2014).

These findings highlight KYNA’s role in the pathophysiology of neurodegeneration and mental disorders, potentially through mechanisms involving oxidative stress, glutamatergic excitotoxicity, and inflammation. The participation of gut microbiota associated with the alternative routes to KYNA production involving D-amino acids and free radicals may also be relevant here (Ramos-Chávez et al. 2018).

The white-paper, Complex chronic diseases have a common origin, published by biocrates in 2023, includes a discussion of the relationship between KYNA, NDMA receptors and major depressive disorder (MDD). While KYNA inhibits the NMDA receptor and is considered neuroprotective, its fellow kynurenine metabolite quinolinic acid (QUIN) has the opposite effect and is considered neurotoxic. The QUIN/KYNA ratio is increased in the serum of patients with MDD) compared to healthy subjects, and correlates with the duration of remission, suggesting a role for these metabolites in disease progression (Savitz et al. 2015).

A metabolomics study by Erabi et al. found that KYNA was decreased in MDD, and lower levels showed a better therapeutic response to escitalopram (Erabi et al. 2020). This suggests KYNA is a potential overlapping biomarker in diagnosis and predicting therapeutic response.

KYNA does not effectively cross the blood-brain barrier, therefore limiting the potential efficacy of oral administration of KYNA in mitigating neurological and psychological diseases (Turska et al. 2022).

Kynurenic acid and cancer

Kynurenic acid’s effects in the periphery are not as well understood as its role in the brain. Still, there is a growing – if ambiguous – body of evidence confirming the presence of KYNA in several types of cancer in tumor tissue from patients with colon adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (Walczak et al. 2020). Elevated levels of KYNA have been found in the serum of patients with colon adenocarcinoma and lung cancer, and have been associated with invasiveness of lung cancer. In other cases, such as glioblastoma, cervical and prostate cancer, KYNA levels have been found to be lower than in healthy controls.

The precise mechanisms remain unclear. One possibility is that KYNA’s action on GPR35 initiates carcinogenesis and influences cell proliferation, survival and metastasis (Basson et al. 2023). KYNA may also interfere with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) pathways, which is central to cancer biology. And as noted, KYNA activates the AhR pathway, which is also commonly activated in cancer patients, though data suggests this can be both pro- and anti-metastatic (Basson et al. 2023).

Multiple clinical trials are investigating the kynurenine pathway as a potential target for cancer therapies. More research is needed to understand where KYNA fits in the puzzle.

Kynurenic acid and metabolic diseases

Metabolomic and epidemiological research has shown that KYNA may play a role in diabetes and other metabolic diseases, and may protect against obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Zhen et al. 2022). Deficiency in dietary KYNA is associated with adipose tissue dysfunction, with links to insulin sensitivity, energy homeostasis and lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Tomaszewska et al. 2019). In contrast, KYNA synthesis may be influenced by physical exercise, potentially resulting in increased thermogenesis and helping to limit weight gain, insulin resistance and inflammation (Zhen et al. 2022).

Metabolomics research is increasing our understanding of the role of KYNA in metabolic disease and in turn revealing potential therapeutic targets. For example, a recent metabolomics study using an animal model found that KYNA production increases following hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury, which diverts resources from NAD synthesis (Xu. et al. 2022). Augmenting NAD levels were found to mitigate oxidative stress, inflammation and cell death in the liver.

References

Albuquerque et al.: Kynurenic acid as an antagonist of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain: facts and challenges. (2013) Biochem Pharmacol. 85 (8) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2012.12.014.

Basson, C. et al.:The tryptophan–kynurenine pathway in immunomodulation and cancer metastasis. (2023) Cancer Medicine 12 (18) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.6484.

Cai, Y. et al.: Kynurenic acid may underlie sex-specific immune responses to COVID-19. (2021) Sci Signal. 14 (690) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.abf8483.

Chang, KH. et al.: Alternations of Metabolic Profile and Kynurenine Metabolism in the Plasma of Parkinson’s Disease. (2018) Mol Neurobiol. 55 (8) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-017-0845-3.

Cryan, J. et al.: Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. (2012) Nat Rev Neurosci. 13 (10) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3346.

Dehhaghi, M. et al.: Microorganisms, Tryptophan Metabolism, and Kynurenine Pathway: A Complex Interconnected Loop Influencing Human Health Status. (2019) Int J Tryptophan Res. 12 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1178646919852996.

Dehhaghi, M. et al.: The Gut Microbiota, Kynurenine Pathway, and Immune System Interaction in the Development of Brain Cancer. (2020) Front Cell Dev Biol. 8 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.562812.

Desbonnet, L. et al.: The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: An assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. (2008) Journal of Psychiatric Research 43 (2) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.009.

Ellinger, A.: Die Entstehung der Kynurensäure.(1904) Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 43: 325–337. | https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/bchm2.1905.43.3-4.325/html?lang=en

Erabi et al.: Kynurenic acid is a potential overlapped biomarker between diagnosis and treatment response for depression from metabolome analysis. (2020) Scientific Reports 10 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73918-z.

Friedman, M et al.:Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. (2018) International Journal of Tryptophan Research 11 | https://doi.org/10.1177/1178646918802282.

Hou, Y. et al.: Tryptophan Metabolism and Gut Microbiota: A Novel Regulatory Axis Integrating the Microbiome Immunity, and Cancer. (2023) Metabolites 13 (11) | DOi: https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13111166.

Kapolka, N. et al.: DCyFIR: a high-throughput CRISPR platform for multiplexed G protein-coupled receptor profiling and ligand discovery. (2020) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2000430117.

Liebig, J.:Ueber Kynurensäure. (1853) Justus Liebig’s Ann Chem. 86: 125–126. | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jlac.18530860115.

Purton, T. et al.: Prebiotic and probiotic supplementation and the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway: A systematic review and meta analysis Author links open overlay panel. (2021) Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 123 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.026.

Ramos-Chávez, L. et al.: Relevance of Alternative Routes of Kynurenic Acid Production in the Brain. (2018) Oxid Med Cell Longev. 5272741. | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5272741.

Rossi, F. et al.: The Synthesis of Kynurenic Acid in Mammals: An Updated Kynurenine Aminotransferase Structural KATalogue. (2019) Front Mol Biosci. 6 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2019.00007.

Sadok, I. et al.: Dietary Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites—Source, Fate, and Chromatographic Determinations. (2023) Int J Mol Sci. 24 (22) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242216304.

Savitz J et al.: The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. (2020) Molecular psychiatry | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0414-4.

Savitz, J. et al.: Reduction of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid ratio in both the depressed and remitted phases of major depressive disorder. (2015) Brain Behav Immun. 46 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.02.007.

Schwarcz, R. et al.: Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. (2012) Nature Reviews Neuroscience 13 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3257.

Stone, T.: Does kynurenic acid act on nicotinic receptors? An assessment of the evidence. (2020) Journal of Neurochemistry 152 (6) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.14907.

Stone, T.: Inhibitors of the kynurenine pathway Author links open overlay panel. (2000) European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 35 (2) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0223-5234(00)00121-5.

Stone, T.et al.: The kynurenine pathway as a therapeutic target in cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. (2013) British Journal of Pharmacology 169 (6) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.12230.

Tomaszewska, E. et al.: Chronic dietary supplementation with kynurenic acid, a neuroactive metabolite of tryptophan, decreased body weight without negative influence on densitometry and mandibular bone biomechanical endurance in young rats. (2019) PLoS One 14 (12) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226205.

Tsuji, A. et al.:The Tryptophan and Kynurenine Pathway Involved in the Development of Immune-Related Diseases. (2023) Int J Mol Sci. 24 (6) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065742.

Turska, M. et al.: A Review of the Health Benefits of Food Enriched with Kynurenic Acid. (2022) Nutrients 14 (19) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194182.

Turski, M. et al.: Kynurenic Acid in the Digestive System—New Facts, New Challenges. (2013) Int J Tryptophan Res. 6 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.4137/IJTR.S12536.

Turski, M. et al.: Presence of kynurenic acid in food and honeybee products. (2009) Amino Acids 36 (1) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-008-0031-z.

Walczak, K. et al.: Kynurenic acid and cancer: facts and controversies. (2020) Cell Mol Life Sci. 77 (8) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03332-w.

Wennström, M. et al.:Kynurenic Acid Levels in Cerebrospinal Fluid from Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies. (2014) International Journal of Tryptophan Research 7 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.4137/IJTR.S139.

Wirthgen, E. et al.: Kynurenic Acid: The Janus-Faced Role of an Immunomodulatory Tryptophan Metabolite and Its Link to Pathological Conditions. (2017) Front. Immunol., Sec. Immunological Tolerance and Regulation 8 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01957.

Wróbel-Kwiatkowska, M. et al.: Determination of Bioactive Compound Kynurenic Acid in Linum usitatissimum L. (2024) Molecules 29 (8) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29081702.

Xu, B. et al.: Metabolic Rewiring of Kynurenine Pathway during Hepatic Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury Exacerbates Liver Damage by Impairing NAD Homeostasis. (2022) Adv Sci (Weinh). 9 (35) | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202204697.

Zhen, D. et al.: Kynurenic Acid Acts as a Signaling Molecule Regulating Energy Expenditure and Is Closely Associated With Metabolic Diseases. (2022) Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.847611.