- History & Evolution

- Biosynthesis & dietary uptake

- Homovanillic acid and the microbiome

- Homovanillic acid and neurology

- Homovanillic acid and oncology

- Homovanillic acid and 5P medicine

- References

History & Evolution

1950s: discovery | 1963: detected in brain and cerebrospinal fluid (Andén, N. et al., 1963) | 1985: metabolic pathway identified (Westerink, B., 1985)

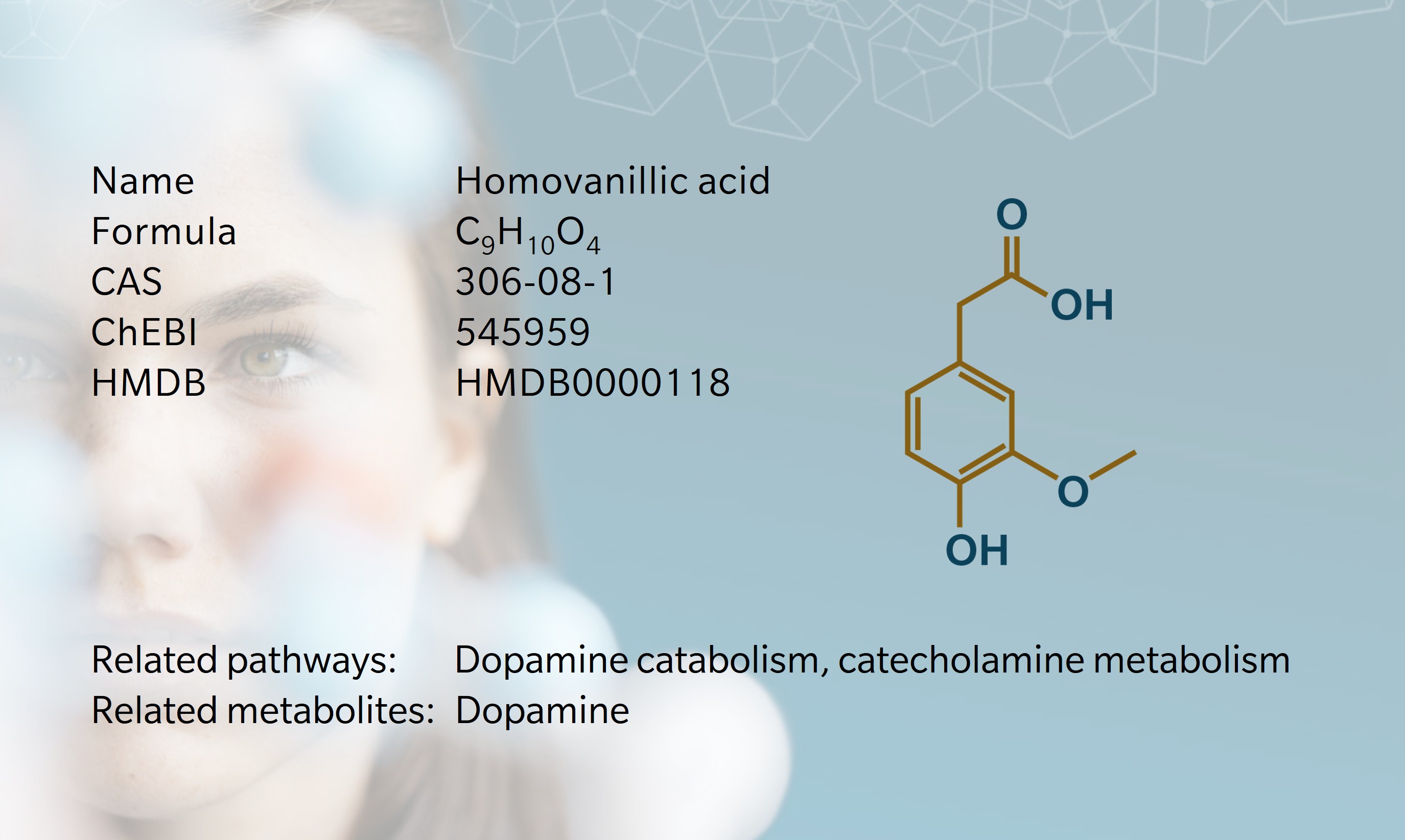

Homovanillic acid (HVA) is a monocarboxylic acid best known for its role as a major dopamine metabolite. The name “homovanillic” refers to the compound’s relationship to vanillic acid, a similar phenolic acid, with the prefix homo- indicating the addition of a methylene group (–CH2–) between the aromatic ring and the carboxyl group.

Interest in HVA began in the 1950s and 60s, when early chromatography studies detected HVA in the urine of mammals and identified it as a marker of dopamine turnover in the brain (Armstrong, M. et al., 1956) (Williams, C. et al., 1960). In 1963, Andén et al. showed that HVA was present in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and introduced a fluorometric method for its detection (Andén, N. et al., 1963). Following the dopamine thread, researchers in the following decades focused on the associations between HVA, dopamine and neurological and psychiatric disorders, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), schizophrenia, depression and, more recently, neuroblastoma. Current research is directed at improving HVA’s diagnostic and prognostic utility as a biomarker in these conditions and refining techniques for its detection in different bodily fluids.

Although primarily found in humans and other mammals, as a phenolic compound HVA is also detectable in some bacteria and plants (Marhuenda-Muñoz, M. et al., 2019). It has been identified in beer, suggesting it can be produced during the fermentation process by microorganisms (Montanari, L. et al., 1999).

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

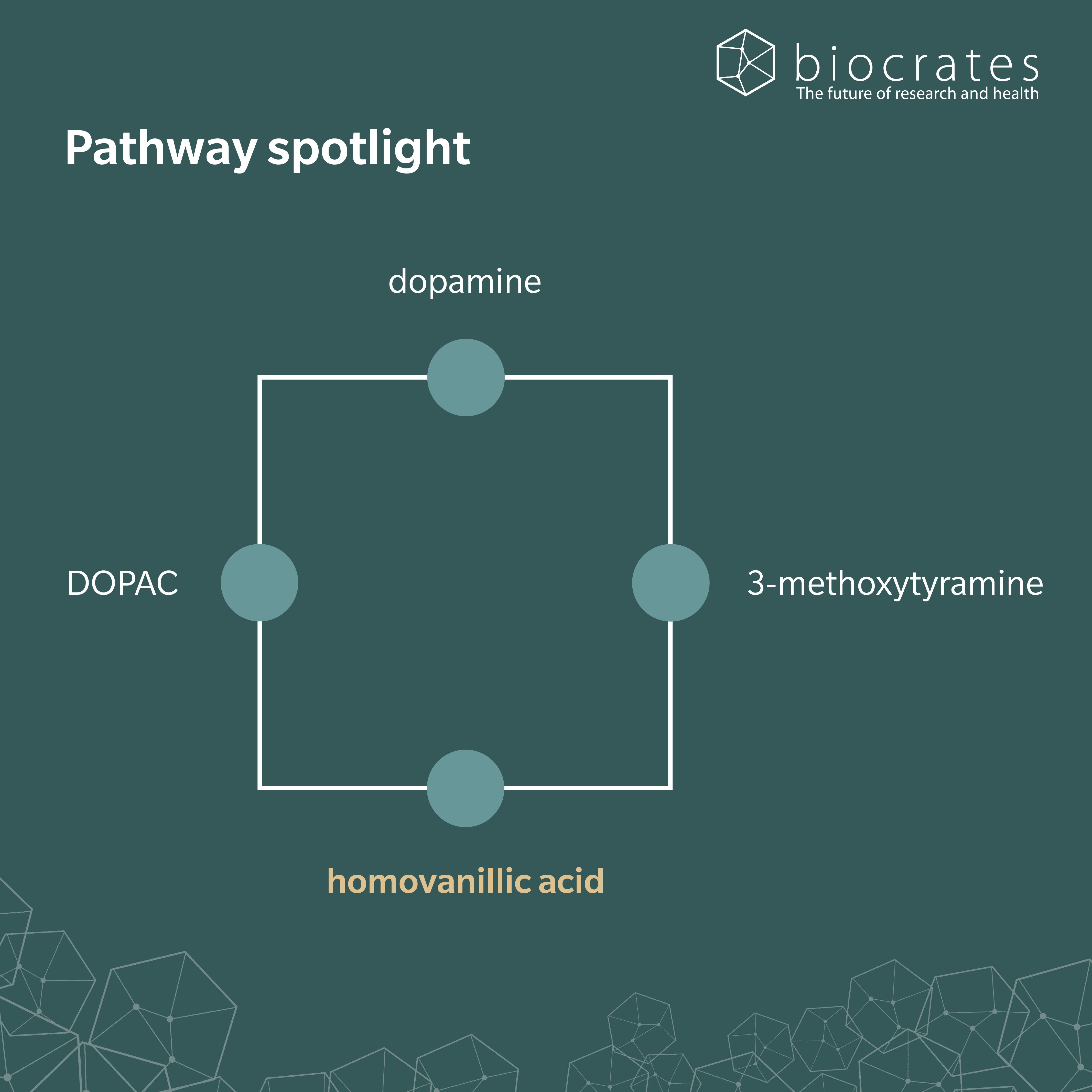

HVA forms in the body as the final breakdown product of dopamine, through a two-step enzymatic process (Buleandră, M. et al., 2025). First, monoamine oxidase (MAO) breaks down dopamine into 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) in dopaminergic neurons in the brain. Then, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) methylates DOPAC and converts it to HVA. An alternative pathway involves COMT acting on dopamine to form 3-methoxytyramine, which MAO then breaks down to form HVA. HVA can also be biosynthesized from homovanillin through the action of the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase.

HVA enters the circulation from both the brain and peripheral tissues such as the lungs, liver and skeletal muscle, and is mainly excreted via the kidneys (Lambert, G. et al., 1993).

Clinically, HVA can be measured in urine, plasma and CSF. Because of the distance between site of production and site of measurement, all three matrices can be vulnerable to confounding factors (Amin, F. et al., 1992). In healthy adults, CSF concentrations typically fall in the range of hundreds of nanomoles per liter (Blennow, K. et al., 1993). Reference ranges for urinary HVA are between 0.8 to 35.0 µmol/mmol of creatinine (Newcastle Hospital). Plasma HVA has a half-life of around one hour, and may be affected by diet for several hours (Köhnke, M. et al., 2003). Fasting plasma levels vary by sex and age, and differences between females and males hold regardless of menopause and hormone treatments in transgender patients (Giltay, E. et al., 2005).

HVA may also form through dietary and microbial pathways. Dietary flavonols commonly found in tomatoes, onions, and tea, can lead to significantly elevated levels of urinary HVA (Combet, E. et al., 2011). Likewise, the microbial digestion of hydroxytyrosol (found in olive oil) can also lead to elevated levels of HVA in humans (Tuck, K. et al., 2002).

Homovanillic acid and the microbiome

Research shows links between HVA and gut microbiota. Zhao et al. found that gut bacterial species, including Bifidobacterium longum and Roseburia intestinalis, were depleted in patients with depression (Zhao, M. et al, 2024). Using metabolomics, they showed that B. longum could directly produce HVA in the gut with the substrates of mouse fodder and tyrosine. R. intestinalis promoted the growth of B. longum, in turn increasing HVA levels in the gut. R. faecis and Eubacterium rectale were also strongly correlated with HVA levels.

Another recent metabolomics study by Gątarek et al. investigated the relationship between gut-derived metabolites, including HVA, and Parkinson’s disease (Gątarek, P. et al., 2025). Here, urinary metabolite profiles indicated elevated levels of HVA and succinic acid , and reduced levels of trimethylamine N-oxide in PD patients compared to controls. These findings highlight how altered gut microbiota may influence HVA levels and in turn affect host dopamine catabolism.

Homovanillic acid and neurology

As an indicator of dopaminergic activity, HVA has long been studied as a marker in neurological and psychiatric diseases in which dopamine plays a role. In PD, HVA shows different patterns depending on the biological matrix analyzed. While urinary HVA may increase in PD patients compared to controls, CSF HVA levels are significantly lower in patients with PD, particularly those with akinesia, indicating reduced dopaminergic activity (Davidson, D. et al., 1977). HVA concentration increases with levodopa therapy, though this is not always associated with clinical improvement (Jiménez-Jiménez, F. et al., 2014).

Altered HVA has also been described in mood and cognitive disorders. CSF HVA levels are reduced in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease, compared to healthy subjects (Morimoto, S. et al., 2017). In a mouse model, administering HVA was found to improve symptoms of depression by inhibiting synaptic autophagy (Zhao, M. et al, 2024).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has been linked to elevated urinary HVA using metabolomics (Gevi, F. et al., 2020). Higher HVA concentrations have also been associated with greater symptom severity, including agitation, stereotyped behaviors and reduced spontaneous activity (Kaluzna-Czaplinska, J. et al., 2010). Supplementation with vitamin B6, which has been found to be lacking in children with ASD, appears to reduce both HVA concentrations and neurological symptoms (Gątarek, P. et al., 2025). HVA has also been studied in relation to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), though findings are inconclusive (Predescu, E. et al., 2024).

In schizophrenia, plasma and CSF HVA often track with symptom severity, but the relationship is complicated. A 2021 review notes that lower CSF HVA often correlates with more severe symptoms and a poorer prognosis (Gasnier, M. et al., 2021). Other work indicates a positive correlation between HVA concentrations and symptom severity (Mazure, C. et al., 1991). Antipsychotic treatment typically causes an initial increase in HVA, followed by a gradual decrease (Gasnier, M. et al., 2021).

Homovanillic acid and oncology

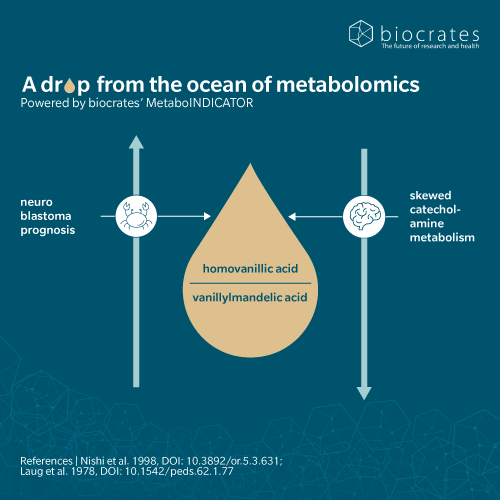

HVA is a marker of catecholamine-secreting tumors, such as neuroblastoma, pheochromocytoma and other neural crest tumors. These tumors secrete excess catecholamines like dopamine, which is then broken down into HVA. Therefore, HVA levels can be a useful indicator of the tumor’s activity. Elevated urinary HVA and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) are detected in children with neuroblastoma, making them standard tools for diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis (Sadilkova, K. et al., 2013). A low VMA to HVA ratio is associated with more aggressive disease (Zambrano, E. and Reyes-Múgica, M., 2002).

Infant screening programs based on HVA/VMA were introduced in Japan and elsewhere in the 1980s, but later abandoned after large trials showed no survival benefit and significant overdiagnosis (Tajiri, T. et al., 2009).

While HVA remains clinically relevant in the diagnosis of neuroblastoma, a scoring system using urinary 3-methoxytyramine sulfate (3-MTS) and vanillactic acid has recently been found to be more sensitive than one based on HVA and VMA (Amano, H. et al., 2024).

Homovanillic acid and 5P medicine

HVA’s relationship to host behavior, genetics and microbial activity makes it highly relevant to 5P medicine. As a marker of dopaminergic function and treatment efficacy, HVA may help to refine and personalize different treatment strategies for patients. Advances in metabolomics now allow rapid, high-sensitivity quantification of HVA and vanillylmandelic acid in urine, streamlining diagnostic processes for a whole range of conditions (Pandya, V. and Frank, E., 2022).

At the population level, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genetic and epidemiological patterns of HVA (Luykx, J. et al., 2014). Multiomics studies are providing further insights, for example, into the causal genetic relationship between HVA and conditions such as eating disorders and schizophrenia (Wen, J. et al., 2025).

Outside the clinic, HVA also plays a role in public health. HVA and related metabolites are used in wastewater-based epidemiology, where their excretion rates correlate with catchment size and provide population-wide biomarkers for exposure and health monitoring (Pandopulos, A. et al., 2021).

References

Amano, H. et al. (2024). Scoring system for diagnosis and pretreatment risk assessment of neuroblastoma using urinary biomarker combinations. Cancer Sci, 115(5), 1634–1645 | https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.16116.

Amin, F. et al. (1992). Homovanillic Acid Measurement in Clinical Research: A Review of Methodology. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 18(1), 123-48 | https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/18.1.123.

Andén, N. et al. (1963). On the occurrence of homovanillic acid in brain and cerebrospinal fluid and its determination by a fluorometric method. Life Sciences, 2(7), 448-458 | https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(63)90132-2.

Armstrong, M. et al. (1956). The Phenolic Acids of Human Urine: Paper Chromatography of Phenolic Acids. J Biol Chem, 218(1), 293-303 | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)65893-4.

Blennow, K. et al. (1993). Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites in 114 healthy individuals 18-88 years of age. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 3(1), 55-61 | https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-977x(93)90295-w.

Buleandră, M. et al. (2025). Electrochemical Study and Determination of Homovanillic Acid, the Final Metabolite of Dopamine, Using an Unmodified Disposable Electrode. Molecules, 30(2), 369 | https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30020369.

Combet, E. et al. (2011). Dietary flavonols contribute to false-positive elevation of homovanillic acid, a marker of catecholamine-secreting tumors. Clinica Chimica Acta, 412(1-2), 165-169 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2010.09.037.

Davidson, D. et al. (1977). CSF studies on the relationship between dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine in Parkinsonism and other movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 40(12), 1136–1141 | https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.40.12.1136.

Gątarek, P. et al. (2025). The Determination of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Organic Acids Connected with Gut Microbiota in the Urine of Parkinson’s Disease Patients: A Pilot Study. Int J Mol Sci, 26(10), 4575 | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26104575.

Gasnier, M. et al. (2021). A New Look on an Old Issue: Comprehensive Review of Neurotransmitter Studies in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Schizophrenia and Antipsychotic Effect on Monoamine’s Metabolism. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci, 19(3), 395–410 | https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2021.19.3.395.

Gevi, F. et al. (2020). A metabolomics approach to investigate urine levels of neurotransmitters and related metabolites in autistic children. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Basis of Disease, 1866(10), 165859 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165859.

Giltay, E. et al. (2005). The sex difference of plasma homovanillic acid is unaffected by cross-sex hormone administration in transsexual subjects. Journal of Endocrinology, 187(1) | https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.1.06307.

Jiménez-Jiménez, F. et al. (2014). Cerebrospinal fluid biochemical studies in patients with Parkinson’s disease: toward a potential search for biomarkers for this disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 8 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00369.

Köhnke, M. et al. (2003). Plasma Homovanillic Acid: A Significant Association with Alcoholism is Independent of a Functional Polymorphism of the Human Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Gene. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, 1004–1010 | https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300107. Retrieved from Neuropsychopharmacology volume 28, pages1004–1010 (2003).

Kaluzna-Czaplinska, J. et al. (2010). Determination of homovanillic acid and vanillylmandelic acid in urine of autistic children by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Medical Science Monitor, 16(9), CR445-50.

Lambert, G. et al. (1993). Regional homovanillic acid production in humans. Life Sciences, 53(1), 63-75 | https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(93)90612-7.

Luykx, J. et al. (2014). Genome-wide association study of monoamine metabolite levels in human cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Psychiatry, 19(2), 228-34 | https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.183.

Marhuenda-Muñoz, M. et al. (2019). Microbial Phenolic Metabolites: Which Molecules Actually Have an Effect on Human Health? Nutrients, 11(11), 2725 | https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112725.

Mazure, C. et al. (1991). Plasma Free Homovanillic Acid (HVA) as a Predictor of Clinical Response in Acute Psychosis. Biol Psychiatry, 30(5), 475-82 | https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(91)90309-a.

Montanari, L. et al. (1999). Organic and Phenolic Acids in Beer. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 32(8), 535-539 | https://doi.org/10.1006/fstl.1999.0593.

Morimoto, S. et al. (2017). Homovanillic acid and 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid as biomarkers for dementia with Lewy bodies and coincident Alzheimer’s disease: An autopsy-confirmed study. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0171524 | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171524.

Pandopulos, A. et al. (2021). Application of catecholamine metabolites as endogenous population biomarkers for wastewater-based epidemiology. Science of The Total Environment, 763, 142992 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142992.

Pandya, V. and Frank, E. (2022). A Simple, Fast, and Reliable LC-MS/MS Method for the Measurement of Homovanillic Acid and Vanillylmandelic Acid in Urine Specimens. Methods Mol Biol, 2546, 175-183 | https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2565-1_16.

Predescu, E. et al. (2024). Metabolomic Markers in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) among Children and Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci, 25(8), 4385 | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25084385.

Sadilkova, K. et al. (2013). Analysis of vanillylmandelic acid and homovanillic acid by UPLC–MS/MS in serum for diagnostic testing for neuroblastoma. Clinica Chimica Acta, 424, 253-257 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.06.024.

Tajiri, T. et al. (2009). Risks and benefits of ending of mass screening for neuroblastoma at 6 months of age in Japan. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 44(12), 2253-2257 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.07.050.

Tuck, K. et al. (2002). Structural characterization of the metabolites of hydroxytyrosol, the principal phenolic component in olive oil, in rats. J Agric Food Chem, 50(8), 2404-9 | https://doi.org/10.1021/jf011264n.

Wen, J. et al. (2025). From Clinic to Mechanisms: Multi-Omics Provide New Insights into Cerebrospinal Fluid Metabolites and the Spectrum of Psychiatric Disorders. Molecular Neurobiology, 62, 9120–9132 | https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-025-04773-0.

Williams, C. et al. (1960). In vivo alteration of the pathways of dopamine metabolism. American Journal of Physiology, 199(4), 722-726 | https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.199.4.722.

Zambrano, E. and Reyes-Múgica, M. (2002). Hormonal activity may predict aggressive behavior in neuroblastoma. Pediatr Dev Pathol, 5(2), 190-9 | https://doi.org/10.1007/s10024001-0145-8.

Zhao, M. et al. (2024). Gut bacteria-driven homovanillic acid alleviates depression by modulating synaptic integrity. Cell Metabolism, 36(5), 1000-1012.e6 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2024.03.010.