How do cancer cells power their relentless growth? Investigating energy metabolism with metabolomics shows us how, with promising opportunities for research and therapy.

The metabolic demands of cancer

Unlimited proliferation is a hallmark of cancer (Hanahan et al. 2000). To sustain this relentless growth, cancer cells require vast amounts of energy. They achieve this by hijacking the cell’s energy metabolism and pushing it into overdrive.

This article explores the ways cancer reprograms core metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, oxidative phosphorylation and lipid metabolism. It also looks at how metabolomics is helping us understand more about these changes, with implications for biomarker discovery and therapeutic interventions.

The Warburg effect – speed over efficiency

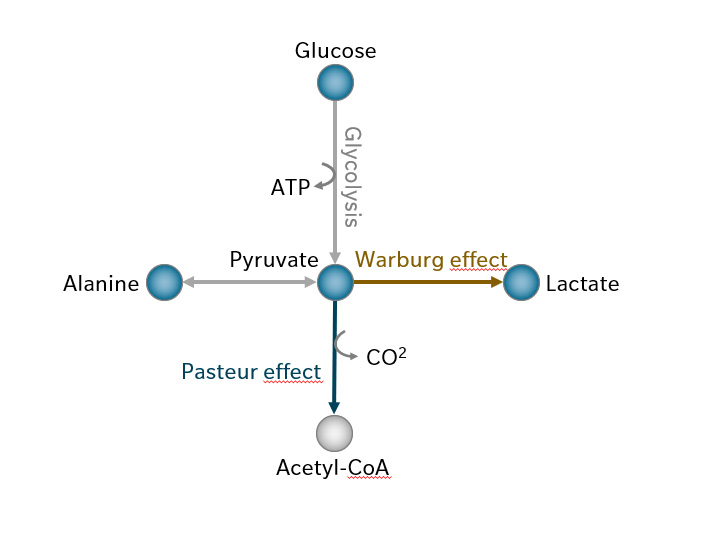

The main strategy cancer cells use to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is aerobic fermentation. Remarkably, many cancer cells convert pyruvate from glycolysis into lactate, instead of the more efficient option of sending it into mitochondria to form acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) (Figure 1) (Finley 2023).

Why this counterintuitive choice? As Otto Warburg observed over a century ago, glycolysis produces ATP more quickly than oxidative phosphorylation, and as long as glucose is abundant, speed outweighs efficiency (Thompson et al. 2023).

Figure 1: Under normal oxygen conditions, pyruvate from glycolysis is transported to the mitochondria and converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase (the Pasteur effect), suppressing fermentation that would usually occur in the absence of oxygen. The Warburg effect describes how cancer cells continue fermenting pyruvate to lactate even when oxygen is available. Pyruvate is also in balance with alanine via alanine transferase. Metabolites covered by biocrates kits are highlighted in blue.

Since the discovery of the ‘Warburg effect’, major advances have reshaped our understanding of cancer metabolism. Early theories that cancer cells rely on glucose fermentation because of mitochondrial damage have given way to evidence that mitochondrial function remains largely intact in many cancer types. What changes is the fuel for the TCA cycle: it shifts from glycolysis to glutaminolysis, allowing mitochondria to generate energy while glycolytic intermediates are diverted to biosynthetic pathways that support rapid cell growth (Mathew et al. 2024). Mitochondria are still crucial for cancer cells, not as energy bottlenecks, but as hubs that coordinate energy production with biosynthesis.

TCA cycle and oncometabolites

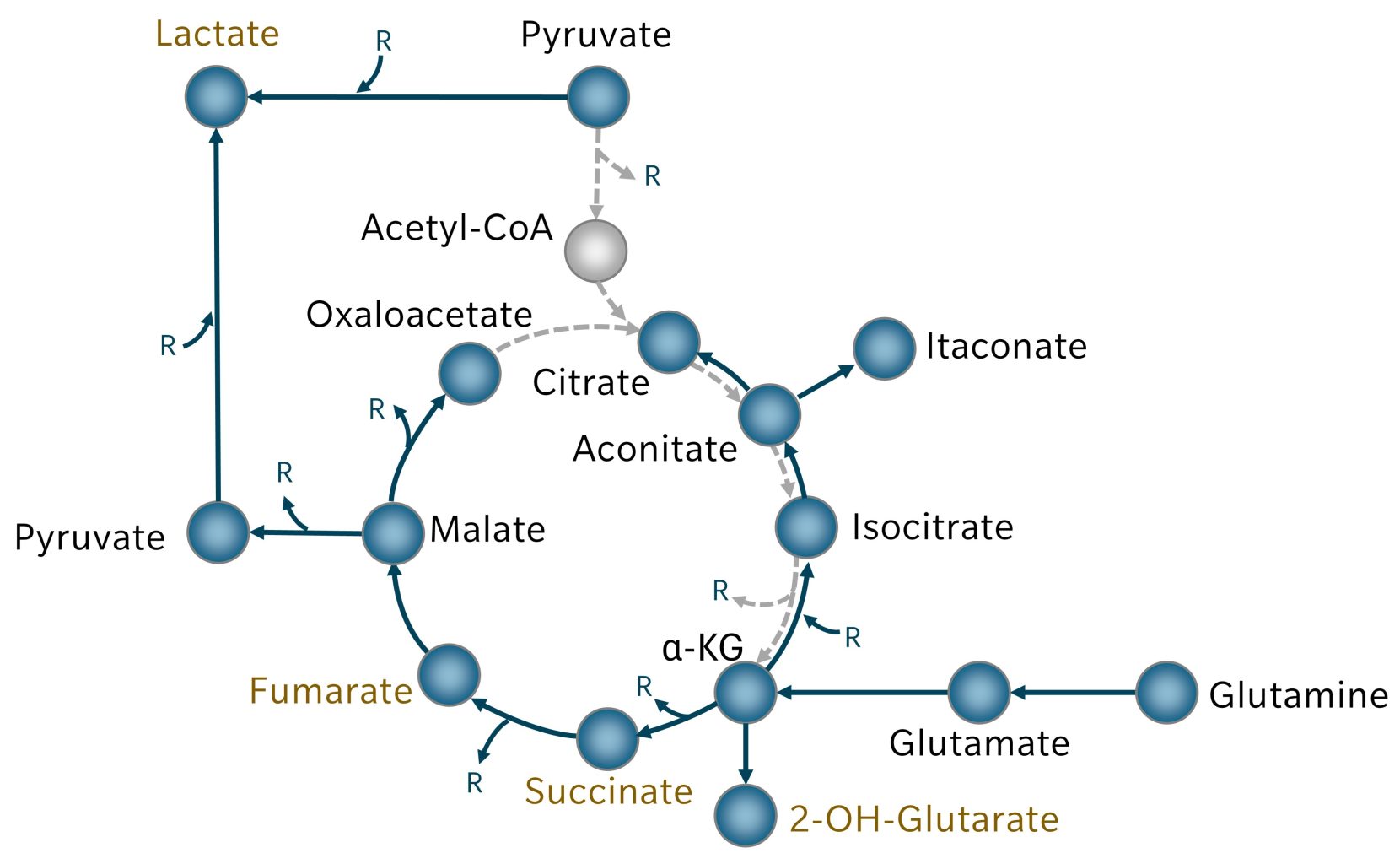

Because the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA is limited in many cancer cells, the TCA cycle is replenished primarily through glutaminolysis. Glutamine is converted to glutamate, which produces alpha-ketoglutarate (αKG) and downstream TCA cycle metabolites up to oxaloacetate (Figure 2). Limited acetyl-CoA reduces citrate synthesis from oxaloacetate, but citrate can instead be generated in reverse from αKG via reductive carboxylation and becomes a source for acetyl-CoA for biosynthesis.

A glutaminolysis-driven TCA cycle produces fewer reducing equivalents for oxidative phosphorylation but generates ample intermediates for proliferation, while glycolysis remains the primary energy source (Mathew et al. 2024). Oxaloacetate accumulation drives malate conversion to pyruvate and lactate, meaning lactate is produced from both glycolysis in the cytosol and mitochondrial glutaminolysis.

Once considered a waste product, lactate is now recognized as a key oncometabolite. It supplies carbon to cancer cells and helps maintain a low pH in the tumor microenvironment, which promotes tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. It inhibits cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells while supporting immunosuppressive populations such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Lactate also impairs dendritic cell function, limiting the presentation of tumor antigens (Chen et al. 2024).

Recent studies have revealed additional tumor-promoting effects. Through histone lactylation, lactate regulates gene expression, activating tumor-promoting pathways, including immune suppression. Lactate also acts as a signaling molecule, binding to G-protein-coupled receptors on immune and tumor cells to facilitate immune evasion (Chen et al. 2024).

Figure 2: In cancer cells, TCA cycle metabolites are replenished by glutaminolysis. Reactions that are reduced as a result are depicted in broken grey arrows. Metabolites covered by biocrates kits are highlighted in blue. Oncogenes are highlighted in ochre font. R = Reductive equivalents

The TCA cycle also gives rise to important oncometabolites like 2-hydroxyglutarate, succinate and fumarate:

- Accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate results from mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 or 2, found in multiple cancer types. This produces D-2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits αKG-dependent dioxygenases, disrupting DNA and histone methylation, and promoting tumorigenesis and progression (Xu et al. 2011). αKG can also be converted to L-2-hydroxyglutarate. Normally, L-2-hydroxyglutarate is degraded by L-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (L2HGDH), but in some cancers, L2HGDH activity is reduced, leading to 2-hydroxyglutarate accumulation without IDH mutation (Lanzetti 2024).

- Succinate accumulates when mutations disrupt the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) complex. Excess succinate blocks αKG-dependent enzymes, which inhibits key regulators including the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), DNA repair enzymes and antioxidant proteins. Succination of prolyl hydroxylases, essential for oxygen sensing, leads to pseudohypoxia, in turn driving tumor-promoting gene expression.

- Fumarate accumulates in cancers with mutations in fumarate hydratase (FH). Like succinate, it blocks αKG-dependent enzymes and induces pseudohypoxia, but it also inactivates glutathione, leading to reactive oxygen species (ROS) buildup and oxidative stress (Lanzetti 2024).

Redox balance and ROS

Energy metabolism is tightly linked to redox balance and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling. The TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation supply reducing equivalents to the electron transport chain. Imbalances in this flow produce ROS, which can act both as damaging agents and as signaling molecules.

Although ROS accumulation might seem detrimental to tumors, given that many anti-cancer drugs rely on ROS to trigger apoptosis, moderate ROS levels actually support cancer progression. At controlled levels, ROS act as signaling molecules that activate pro-survival pathways, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). They also induce tumor-promoting transcription factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), supporting proliferation, angiogenesis and metabolic adaptation. Cancer cells carefully regulate ROS to avoid cytotoxicity while maintaining a level that favors growth and survival. For instance, fumarate not only inactivates glutathione but also covalently modifies reactive cysteine residues on Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), leading to the release of nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NRF2), which drives an antioxidant gene program (Brunner et al. 2023).

The TCA cycle also gives rise to itaconic acid, derived from cis-aconitate via aconitate decarboxylase 1, an enzyme upregulated in activated macrophages. Structurally similar to succinate and fumarate, itaconate inhibits succinate dehydrogenase, which often has anti-inflammatory effects. In tumors, however, tumor-associated macrophages can accumulate itaconate, enhancing oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial ROS production, which promotes tumor growth (Weiss et al. 2018). Extracellular itaconate can be taken up by tumor cells, where it induces immune evasion and survival pathways (Fan et al. 2025).

Branching out from the TCA cycle, the porphyrin/heme pathway is critical for redox balance in cancer. Succinyl-CoA combines with glycine via aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS) to initiate heme synthesis. Some tumors increase ALAS activity, leading to excess production of 5-amino-4-oxovaleric acid (AOVA) (Huang et al. 2017; Zhao et al. 2020). In other cancers, transporters importing AOVA are overexpressed (Harada et al. 2022). The resulting accumulation of protoporphyrin IX downstream in heme synthesis promotes ROS generation, driving tumor proliferation (Owari et al. 2022). Accordingly, AOVA can be considered an oncometabolite-like molecule, despite its primary role as a metabolic intermediate.

Heme itself is pro-oxidant, but its catabolism via heme oxygenase produces biliverdin and bilirubin, which are potent antioxidants. Upregulation of this catabolic pathway helps tumor cells neutralize excess ROS and maintain survival under oxidative stress (Chiang et al. 2018).

Lipid metabolism in energy supply and signaling

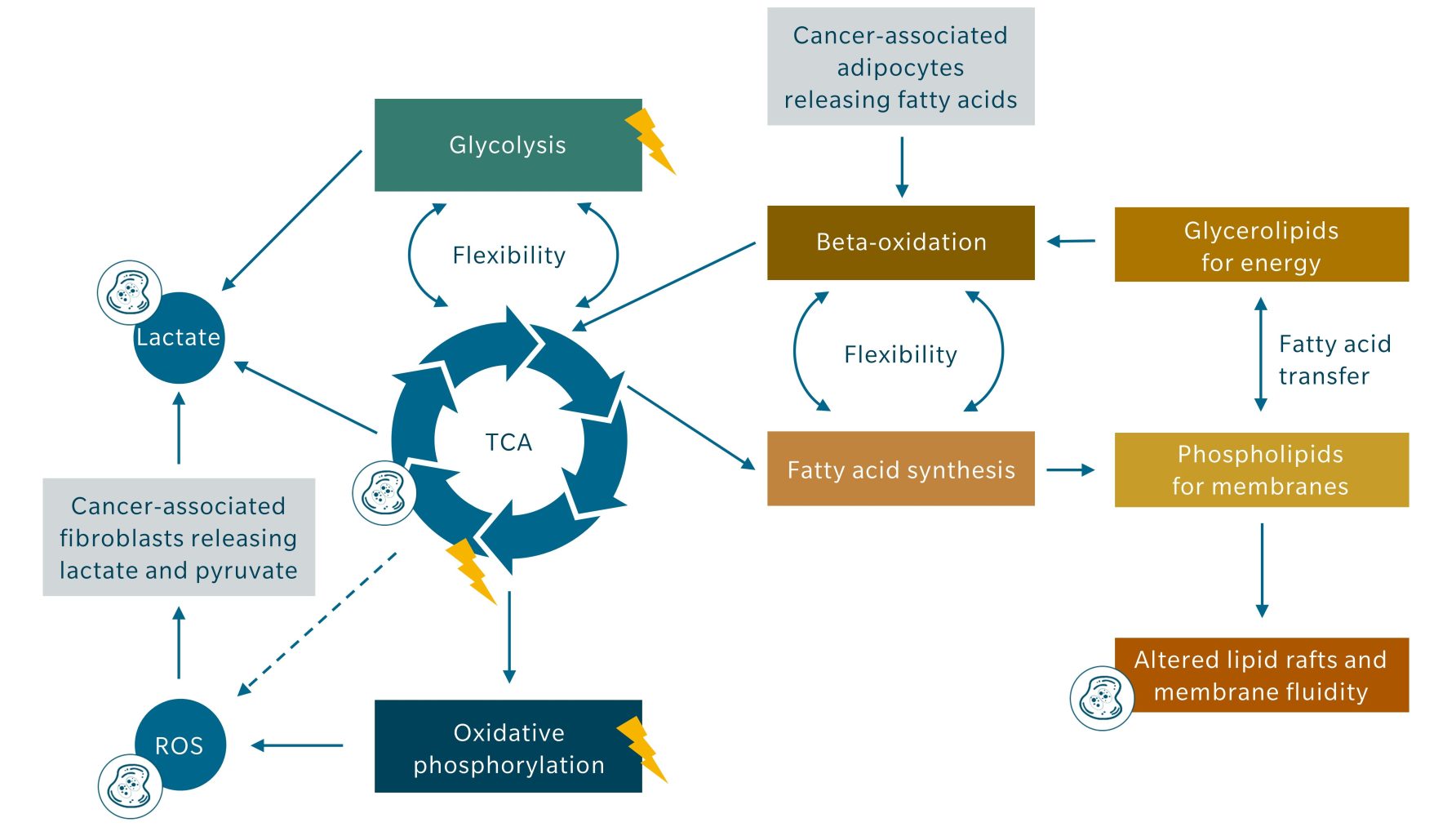

In addition to glycolysis and amino acid catabolism, lipid metabolism is a key energy pathway feeding into oxidative phosphorylation that is frequently rewired in cancer cells. Lipids function not only as an energy source, but also as signaling molecules and membrane building blocks necessary for proliferation.

Although glycolysis often dominates cancer cell energy metabolism, beta-oxidation of fatty acids contributes significantly to ATP production. To meet this demand, cancer cells release exosomes containing pro-lipolytic factors that stimulate adipocytes in the tumor microenvironment. These break down stored lipids and release free fatty acids, which are then readily taken up by tumor cells. Beta-oxidation generates large amounts of acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle to produce reducing equivalents for ATP generation. Odd-chain fatty acids, though less frequent in the human diet, yield propionyl-CoA as well, which is converted into succinyl-CoA and integrated into the TCA cycle.

Even in the presence of external lipid sources, cancer cells frequently upregulate de novo fatty acid synthesis. Citrate, replenished through glutaminolysis-derived αKG, is converted to acetyl-CoA and then carboxylated to malonyl-CoA, the rate-limiting step in fatty acid synthesis. Sequential condensation of malonyl-CoA molecules produces palmitic acid, which serves as a precursor for longer and unsaturated fatty acids (Koundouros et al. 2020).

Sustained de novo lipogenesis offers cancer cells metabolic flexibility, allowing them to shunt fatty acids into various biosynthetic pathways and generate a diverse pool of lipid species with distinct cellular functions. Altered lipid metabolism modifies membrane fluidity and lipid raft formation, thereby influencing cell signaling. Because fatty acid synthesis contributes directly to growth-factor-dependent oncogenic signaling, it is a promising target in combination with different cancer therapies (Koundouros et al. 2020).

Metabolic plasticity and therapy resistance

Energy metabolism in cancer offers many avenues for therapeutic intervention, but most attempts to exploit them have failed in clinical translation due to the metabolic plasticity of cancer cells. Rapidly proliferating tumors encounter diverse microenvironments with varying oxygen levels, nutrient availability and surrounding cell types. This metabolic flexibility allows cancer cells to survive under fluctuating conditions and contributes to the transient effectiveness of drugs targeting energy metabolism.

For instance, tumors that rely mainly on glucose metabolism can often adapt to glycolysis-inhibiting treatments by switching to oxidative phosphorylation, and vice versa, depending on tumor type and microenvironment. Similarly, cancer cells that utilize ROS to promote proliferation can counteract drugs that induce excessive ROS by downregulating ROS production and increasing antioxidant synthesis, maintaining a balance that favors survival. The ability to draw on multiple nutrients and pathways makes it unlikely that cancer cells ever run out of energy, even under targeted metabolic interventions (Fendt et al. 2020).

Several large pharmaceutical companies have discontinued research on cancer metabolism after promising targets failed in late preclinical stages or early clinical trials. A key challenge is heterogeneity of metabolic enzymes in tumor tissue, particularly mitochondrial enzymes, which means that treatments targeting energy metabolism rarely affect all cancer cells uniformly.

One strategy that remains promising in some tumor types is autophagy inhibition. Many cancers with mitochondrial defects rely on autophagy-mediated organelle turnover. Blocking this process causes dysfunctional mitochondria to accumulate, which reduces metabolic plasticity and sensitizes cancer cells to energy-targeting therapies (Fendt et al. 2020). However, in tumors without mitochondrial defects and late-stage cancers, autophagy inhibition is associated with poor outcomes, and may even enhance tumor cell survival during stress (Carretero-Fernández et al. 2025).

Microenvironmental contributions to metabolic plasticity

The tumor microenvironment, including the extracellular matrix and adjacent non-cancerous cells, further contributes to metabolic plasticity and therapy resistance. A prominent example is the Reverse Warburg effect, where cancer cells induce aerobic glycolysis in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). These fibroblasts produce high-energy metabolites, such as pyruvate and lactate, which cancer cells use in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, supporting tumor energy metabolism. In this scenario, glycolysis becomes less critical for cancer cells themselves, representing a reversal of the classical Warburg effect.

Cancer cells drive this metabolic reprogramming in fibroblasts via paracrine ROS signaling, mitochondrial stress induction and secretion of proinflammatory proteins. Fibroblasts respond by increasing lactate and pyruvate export, while cancer cells increase lactate importers to efficiently take up these metabolites (Wilde et al. 2017). The stimulation of tumor-adjacent adipocytes to release free fatty acids, as described earlier, follows the same principle of exploiting the microenvironment to sustain cancer cell metabolism. Figure 3 summarizes how the TCA cycle, ROS generation, lipid metabolism and tumor microenvironment interact to sustain tumor energy generation and proliferation.

Figure 3: Illustration of the links between TCA cycle, ROS generation, lipid metabolism and tumor microenvironment contributing to energy generation (symbolized by lightning) and proliferation (symbolized by dividing cell). The dashed line indicates several indirect means by which the TCA cycle metabolites increase ROS generation besides oxidative phosphorylation.

Energy metabolism biomarkers as research tools

While the metabolic plasticity of cancer cells complicates therapeutic targeting, metabolomics offers a window into the pathways that tumors rely on most. By profiling metabolite fluxes, metabolomics can pinpoint which metabolic programs are most active and which are disturbed, with the aim of identifying potential combination strategies for therapy. Metabolomics provides insights into early detection, disease aggressiveness and the efficacy of therapies. Pyruvate levels and the pyruvate-to-lactate ratio are particularly informative here.

A higher pyruvate-to-lactate ratio is generally associated with less malignant tumors, whereas a lower ratio, reflecting increased lactate production, is more typical of aggressive and metastatic cancers. The pyruvate-to-lactate ratio therefore holds promise as a prognostic biomarker and could, in some cases, aid in differential diagnosis (Sharma et al. 2023).

This ratio also provides a metabolic proxy for the redox state of cancer cells. The conversion of pyruvate to lactate consumes reducing equivalents. A low pyruvate-to-lactate ratio indicates a high abundance of reducing equivalents, while a high ratio indicates a low abundance. Radiotherapy and other treatments that generate ROS damage DNA through oxidative stress.

Tumor cells with high reducing potential (i.e., low pyruvate-to-lactate ratio) can better neutralize ROS via glutathione and other antioxidant systems, conferring radioresistance. Accordingly, this ratio has been suggested as a biomarker to predict the effectiveness of ROS-based therapies. Tumors with low pyruvate-to-lactate ratios could benefit from radiosensitizers or combination therapy to enhance treatment efficacy (Sharma et al. 2023).

Animal studies further indicate that in tumor models with a pronounced Warburg effect, decreased pyruvate-to-lactate conversion may be the first sign of treatment response, preceding measurable reductions in tumor growth (Sharma et al. 2023).

The plasma lactate-to-pyruvate ratio is already used as a clinical marker for mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders and inherited pyruvate metabolism defects (Gopan et al. 2021). In cancer, however, only a small subset of cells is affected, meaning systemic changes in plasma are typically observable only in large, highly glycolytic tumors or advanced cancers.

For reliable assessment of energy metabolism in cancer, metabolomic analyses should focus on tissue samples (from biopsies or in-vivo studies) or cells and their culture media (in an in-vitro setting), rather than plasma. These approaches are well-established and provide detailed insights into cancer metabolism by profiling key metabolites and uncovering metabolic vulnerabilities.

Spatial and in-vivo metabolomics for energy metabolism visualization

Spatial metabolomics adds another layer of detail, linking metabolic activity to tissue architecture. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) provides high-resolution maps of energy metabolites within tumors, revealing metabolite gradients and regional specificity of glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation.

A complementary non-invasive approach is hyperpolarized ¹³C pyruvate (HP-pyruvate) magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRI), which enables dynamic real-time imaging of pyruvate conversion to lactate, alanine or bicarbonate. Hyperpolarization enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, allowing differentiation between cancer and normal cells based on upregulated glycolysis. Studies in breast and prostate cancer patients, as well as in animal models, show that HP-pyruvate MRI can detect treatment response earlier than conventional multiparametric MRI (Sharma et al. 2023). With technological advances making hyperpolarization more accessible and cost-effective, HP-pyruvate imaging has the potential to become a widespread translational biomarker, highlighting the clinical relevance of metabolism and expanding interest in metabolomics research.

biocrates kits for energy metabolism research

While emerging imaging techniques such as HP-pyruvate MRI provide dynamic, spatial insights, conventional metabolomics remains the cornerstone for mechanistic studies, biomarker discovery and preclinical validation.

The recently launched MxQuant kit by biocrates measures up to 327 small molecules, offering significantly broader coverage options for energy metabolism studies. The kit assesses almost all key energy metabolites discussed in this article, providing a comprehensive overview of cellular energy metabolism.

For an even more complete picture, the MxP Quant 1000 kit covers all metabolites of the MxQuant kit plus 906 lipids. This links fatty acid consumption with triglyceride stores and fatty acid synthesis with the phospholipid pool, both essential for proliferation and tumor growth. When combined with careful experimental design and emerging technologies, these products offer a robust, accessible approach to study cancer energy metabolism. They are well-positioned to drive discoveries that are both mechanistically illuminating and clinically relevant.

References

Brunner, J.S. et al.: Metabolic determinants of tumour initiation (2023) Nature reviews. Endocrinology | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-022-00773-5.

Carretero-Fernández, M. et al.: Autophagy and oxidative stress in solid tumors: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities (2025) Critical reviews in oncology/hematology | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2025.104820.

Chen, S. et al.: The emerging role of lactate in tumor microenvironment and its clinical relevance (2024) Cancer letters | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216837.

Chiang, S.-K. et al.: A Dual Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Cancer Cells (2018) International journal of molecular sciences | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20010039.

Fan, Y. et al.: Itaconate transporter SLC13A3 confers immunotherapy resistance via alkylation-mediated stabilization of PD-L1 (2025) Cell metabolism | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2024.11.012.

Fendt, S.-M. et al.: Targeting Metabolic Plasticity and Flexibility Dynamics for Cancer Therapy (2020) Cancer discovery | https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0844.

Finley, L.W.S.: What is cancer metabolism? (2023) Cell | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.038.

Gopan, A. et al.: Mitochondrial hepatopathy: Respiratory chain disorders- ‘breathing in and out of the liver’ (2021) World journal of hepatology | https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i11.1707.

Hanahan, D. et al.: The hallmarks of cancer (2000) Cell | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9.

Harada, Y. et al.: 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Induced Protoporphyrin IX Fluorescence Imaging for Tumor Detection: Recent Advances and Challenges (2022) International journal of molecular sciences | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23126478.

Huang, H. et al.: Over expression of 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase 2 increased protoporphyrin IX in nonerythroid cells (2017) Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.10.007.

Koundouros, N. et al.: Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer (2020) British journal of cancer | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0650-z.

Lanzetti, L.: Oncometabolites at the crossroads of genetic, epigenetic and ecological alterations in cancer (2024) Cell death and differentiation | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-024-01402-6.

Mathew, M. et al.: Metabolic Signature of Warburg Effect in Cancer: An Effective and Obligatory Interplay between Nutrient Transporters and Catabolic/Anabolic Pathways to Promote Tumor Growth (2024) Cancers | https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16030504.

Owari, T. et al.: 5-Aminolevulinic acid overcomes hypoxia-induced radiation resistance by enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in prostate cancer cells (2022) British journal of cancer | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01789-4.

Sharma, G. et al.: Enhancing Cancer Diagnosis with Real-Time Feedback: Tumor Metabolism through Hyperpolarized 1-13C Pyruvate MRSI (2023) Metabolites | https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13050606.

Thompson, C.B. et al.: A century of the Warburg effect (2023) Nature metabolism | https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-023-00927-3.

Weiss, J.M. et al.: Itaconic acid mediates crosstalk between macrophage metabolism and peritoneal tumors (2018) The Journal of clinical investigation | https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI99169.

Wilde, L. et al.: Metabolic coupling and the Reverse Warburg Effect in cancer: Implications for novel biomarker and anticancer agent development (2017) Seminars in oncology | https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.10.004.

Xu, W. et al.: Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2011) Cancer cell | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014.

Zhao, Y. et al.: Inhibition of ALAS1 activity exerts anti-tumour effects on colorectal cancer in vitro (2020) Saudi journal of gastroenterology: official journal of the Saudi Gastroenterology Association | https://doi.org/10.4103/sjg.SJG_477_19.