- History & Evolution

- Biosynthesis & dietary uptake

- Bilirubin and the microbiome

- Bilirubin and neurology

- Bilirubin and oncology

- Bilirubin and 5P medicine

- References

History & Evolution

1847: discovery | 1930: first synthesis of heme | 1960s: detoxification pathway elucidated

As early as 400BCE, Hippocratic physicians described yellowing skin as a sign of liver disease – a symptom we now know to be caused by bilirubin (Berk et al. 1977). In 1847, Rudolf Virchow identified the compound responsible for jaundice, as a blood breakdown product, coining the name from bilis (Latin: bile) and rubin (Latin: red) (Lightner 2013).

In the 1930s, chemist Hans Fischer demonstrated that bilirubin originated from the porphyrin ring of hemoglobin (Hopper et al. 2021; Berk et al. 1977). Later developments in chromatographic and spectrophotometric techniques allowed researchers to separate and quantify conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin, greatly advancing clinical diagnostics (Blanckaert et al. 1976; Heirwegh et al. 1989). Understanding of heme catabolism and bilirubin production increased further in the 1960s, when specific enzymatic reactions were identified (Hopper et al. 2021).

More recently, bilirubin has emerged as more than a waste product. Research points to antioxidant and signaling properties with potential cytoprotective effects. For example, patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, a mild hereditary unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, show lower cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk (Fevery 2008).

Biosynthesis vs. dietary uptake

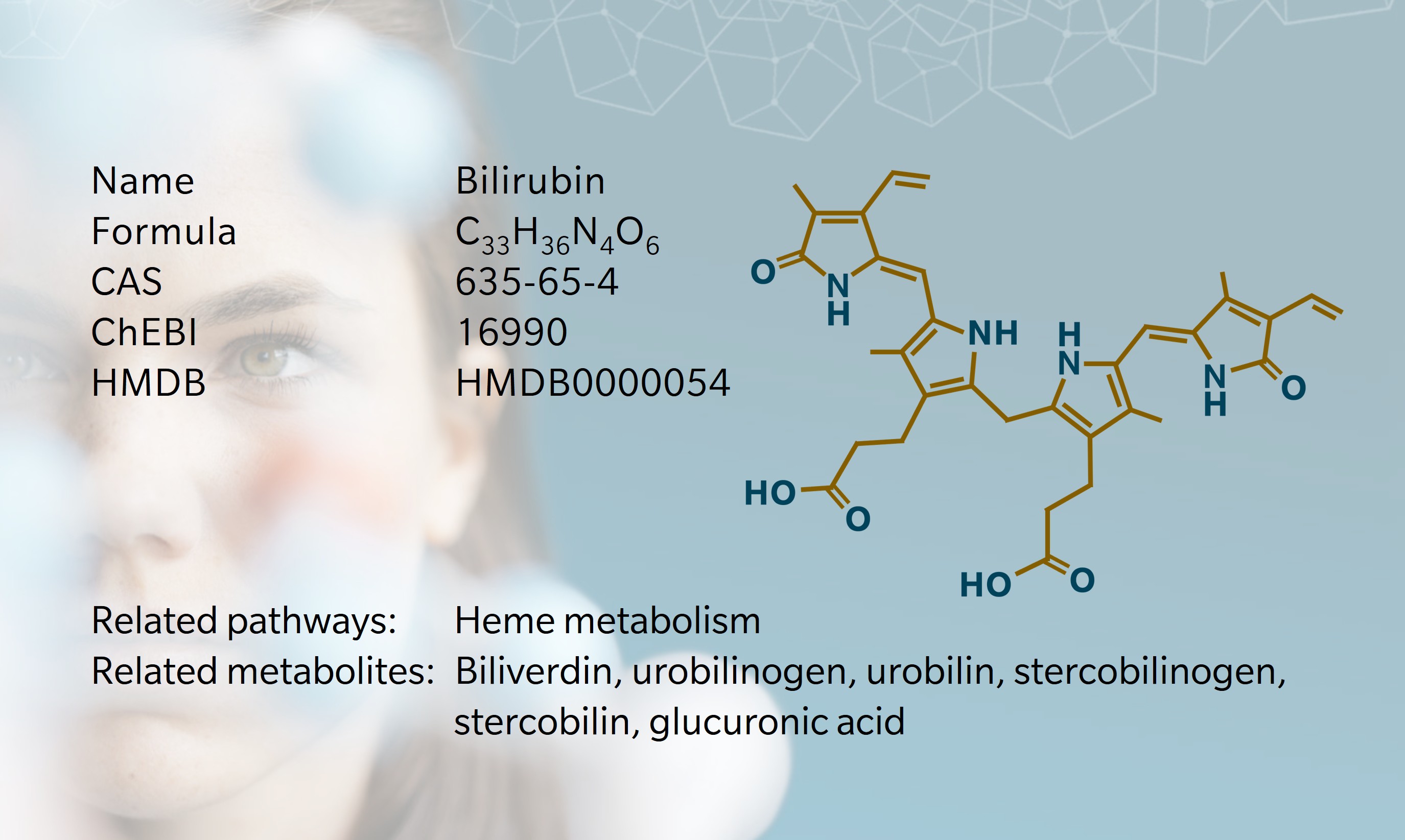

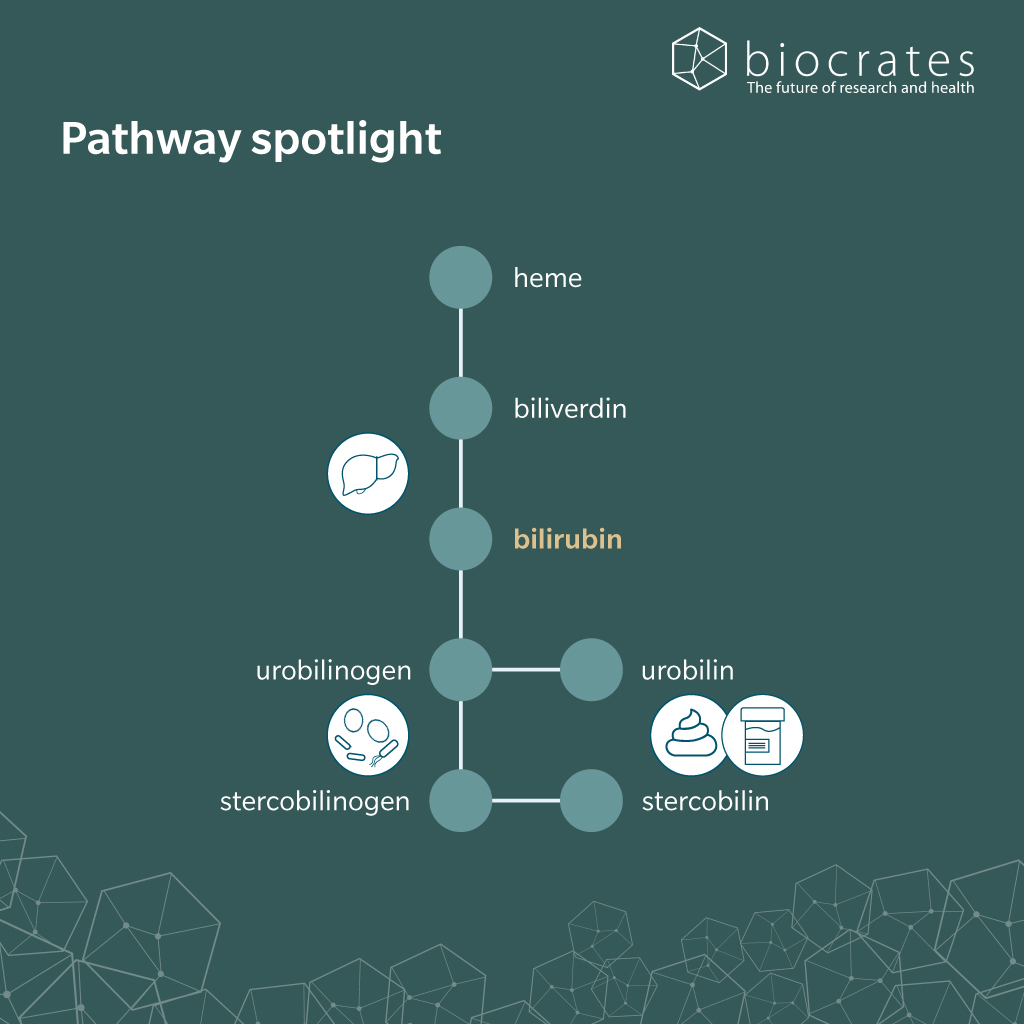

Approximately 80% of bilirubin is derived from hemoglobin catabolism in bone marrow. The remaining 20% originates from the turnover of various heme-containing proteins, primarily in the liver and muscle tissues. This occurs predominantly within the mononuclear phagocyte system, especially in splenic macrophages, hepatic Kupffer cells and bone marrow monocytes (Fevery 2008; Kalakonda et al. 2022).

Heme oxygenase cleaves heme, releasing chelated iron, carbon monoxide and biliverdin (Kalakonda et al. 2022). Biliverdin reductase then rapidly reduces the biliverdin to form bilirubin, a hydrophobic, orange-yellow pigment (Kalakonda et al. 2022). Due to its poor solubility in water, unconjugated bilirubin binds tightly to serum albumin, which facilitates its transport in the bloodstream, prevents renal filtration and protects tissues from bilirubin’s potentially toxic accumulation. Under normal conditions, virtually no free bilirubin is detectable in plasma (Fevery 2008; Kalakonda et al. 2022).

In the liver, bilirubin dissociates from albumin and enters hepatocytes where it is conjugated with one or two molecules of glucuronic acid by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1). This rate-limiting reaction renders bilirubin water-soluble and marks a key detoxification step in heme metabolism (Kalakonda et al. 2022).

Only conjugated bilirubin can be actively secreted into bile, where it forms micelles with bile acids, cholesterol and phospholipids that are delivered to the small intestine (Fevery 2008). There, bacterial enzymes deconjugate and reduce bilirubin to urobilinogen and stercobilinogen. These compounds are oxidized to urobilin and stercobilin, which are excreted in feces and contribute to its characteristic brown color (Kalakonda et al. 2022). Around 10-20% of urobilinogen is reabsorbed into the portal circulation and may reenter the liver as part of the enterohepatic circulation. While the majority of reabsorbed urobilinogen is taken up again by hepatocytes and re-excreted into bile, a small proportion escapes hepatic reuptake and is ultimately excreted in urine (Gilles J. Hoilat et al. 2023). In the urinary tract, urobilinogen can spontaneously oxidize to urobilin, which gives urine its yellow color (Kalakonda et al. 2022).

Bilirubin and the microbiome

Transformation of conjugated bilirubin in the small intestine is largely dependent on the gut microbiota, particularly bacterial enzymes like β-glucuronidases (Leung et al. 2001). Recently, bilirubin reductase (BilR) was identified as the first microbial enzyme that could reduce bilirubin to urobilinogen-like compounds. BilR is expressed by several members of the Firmicutes phylum and supports microbial participation in host heme metabolism (Hall et al. 2024). However, the precise enzymatic steps responsible for converting urobilinogen to stercobilinogen remain undefined.

Microbiome immaturity or disruption can alter this process. In neonates, low BilR activity hinders bilirubin degradation, contributing to neonatal jaundice (Hall et al. 2024; You et al. 2023). In adults, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other forms of dysbiosis may impair bilirubin metabolism, leading to elevated circulating levels and disrupted enterohepatic cycling (Hall et al. 2024).

Importantly, the relationship between bilirubin and the microbiome is bidirectional. By exerting oxidative stress on gram-positive bacteria, bilirubin suppresses microbial growth, while gram-negative taxa such as Bacteroidetes are often positively associated with serum bilirubin levels in human microbiome studies (Nobles et al. 2013; You et al. 2023).

Bilirubin and cardiometabolic disease

As a central product of heme catabolism, bilirubin serves not only as a biomarker of hepatic function but also as a biologically active molecule with far-reaching effects on metabolic health.

Under normal conditions, glucuronidation is the rate-limiting step in bilirubin metabolism. However, it is the canalicular secretion into bile that is most vulnerable to disruption. In conditions such as intrahepatic cholestasis or biliary obstruction, this excretory pathway is impaired, causing conjugated bilirubin to accumulate in the bloodstream (Fevery 2008). Clinically, elevated conjugated and delta bilirubin (bound to albumin) are key indicators of cholestatic liver injury (Kalakonda et al. 2022).

In contrast, unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia arises from overproduction or impaired conjugation of bilirubin, as seen in hemolytic anemia, ineffective erythropoiesis, or genetic disorders such as Crigler–Najjar and Gilbert’s syndrome (Ramírez-Mejía et al. 2024; Fevery 2008).

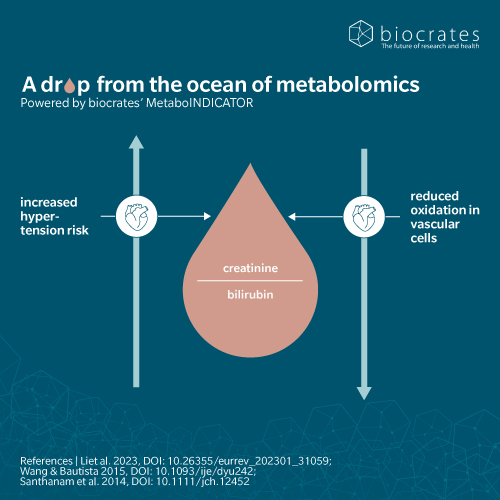

Mechanistic studies suggest that bilirubin acts as a metabolic buffer, through multiple pathways. It scavenges reactive oxygen species, protects vascular endothelium, and downregulates nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and cytokine production. It also reduces lipogenesis, enhances fatty acid oxidation, inhibits gluconeogenesis and improves insulin sensitivity. These actions contribute to a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes, making bilirubin a molecule of increasing interest in preventive metabolic health (Ramírez-Mejía et al. 2024).

Bilirubin and neurology

While bilirubin plays protective roles in peripheral tissues, it poses a distinct risk within the central nervous system. Unconjugated bilirubin is lipophilic and capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier, where it can accumulate in neural tissue. This is especially critical in neonates, whose immature liver conjugation systems, biliary secretory apparatus and microbiota make them highly susceptible to bilirubin neurotoxicity (Fevery 2008).

At the cellular level, unconjugated bilirubin interferes with several neural processes. It impairs mitochondrial function, disrupts energy metabolism and alters neurotransmitter synthesis, release and uptake. It also inhibits glutamate uptake by astrocytes, leading to excitotoxicity – a mechanism associated with neurodegeneration (Ramírez-Mejía et al. 2024). Moreover, bilirubin can trigger neuroinflammation, activating microglia and inducing proinflammatory signaling cascades (Zhang et al. 2023).

Despite these risks, emerging evidence suggests that moderate systemic bilirubin levels may exert neuroprotective effects via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways, potentially influencing cognitive aging and neurodegenerative disease risk (Kaur et al. 2025). However, these dual properties remain context- and concentration-dependent, underlining the need for precise regulation of bilirubin metabolism to protect brain health.

Bilirubin and oncology

Recent research is repositioning bilirubin as a regulatory metabolite in cancer biology. While bilirubin’s systemic antioxidant capacity is well-known, its local effects within the tumor microenvironment and its metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells are gaining attention.

Tumors may actively reshape bilirubin metabolism to modulate intracellular redox states. In some cancers, UGT1A1 is downregulated, allowing unconjugated bilirubin to accumulate and buffer against oxidative stress from rapid proliferation or immune surveillance (Yi et al. 2025). Other tumors upregulate heme oxygenase-1 (Ren et al. 2024), shifting heme metabolism toward biliverdin and carbon monoxide, which contribute to immune modulation and angiogenesis (Loboda et al. 2015).

Bilirubin also affects immune cell function in ways that might either suppress tumor-promoting inflammation or impair antitumor immunity (Yi et al. 2025; Ren et al. 2024). These immunomodulatory effects are being explored in the context of tumor immune evasion and response to immunotherapies (Yi et al. 2025; Lee et al. 2023; Ren et al. 2024).

At the cellular level, bilirubin alters checkpoint regulators, kinase signaling, mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular calcium homeostasis. These changes drive apoptosis, autophagy and growth arrest in cancer cells, while also disrupting invasion and vascular remodeling. Through transcriptional regulators like NF-κB, p53 and extracellular signaling-regulated kinase (ERK), bilirubin shapes the balance between tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressive signaling networks (Yi et al. 2025).

Future research will need to clarify when bilirubin acts as a protective agent and when it might be co-opted as a tumor-supportive factor.

Bilirubin and 5P medicine

Like many metabolites, bilirubin is now seen not just as a simple waste product but also as a multifunctional regulatory molecule. As we learn more about its relevance to cellular and systemic mechanisms, bilirubin will surely make its mark in 5P medicine.

Bilirubin levels are already established biomarkers in clinical diagnostics, predicting liver dysfunction, hemolytic disorders and neonatal risk for kernicterus. Moderate bilirubin elevations have also been associated with reduced cardiovascular and metabolic risk (Ramírez-Mejía et al. 2024), extending its predictive value for chronic disease susceptibility.

The molecule’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties suggest new avenues for preventive strategies in oxidative stress-driven diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes or neurodegeneration (Ramírez-Mejía et al. 2024).

In oncology, the dual role of bilirubin as both a potential tumor-protective and tumor-supportive factor underscores the need for personalized approaches (Ren et al. 2024; Yi et al. 2025). Patient-specific bilirubin metabolism profiles could inform treatment decisions, particularly in immunotherapy and redox-targeted therapies.

References

Berk, P.D. et al.: International Symposium on Chemistry and Physiology of Bile Pigments (1977).

Blanckaert, N. et al.: Synthesis and separation by thin-layer chromatography of bilirubin-IX isomers. Their identification as tetrapyrroles and dipyrrolic ethyl anthranilate azo derivatives (1976) The Biochemical journal | https://doi.org/10.1042/bj1550405

Fevery, J.: Bilirubin in clinical practice: a review (2008) Liver International | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01716.x

Gilles J. Hoilat et al.: Bilirubinuria (2023). | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557439/

Hall, B. et al.: BilR is a gut microbial enzyme that reduces bilirubin to urobilinogen (2024) Nature Microbiology | https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01716.x

Heirwegh, K.P. et al.: Chromatographic analysis and structure determination of biliverdins and bilirubins (1989) Journal of chromatography | https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82549-9

Hopper, C.P. et al.: A brief history of carbon monoxide and its therapeutic origins (2021) Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.001

Kalakonda, A. et al.: Physiology, Bilirubin (2022). | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470290/

Kaur, A. et al.: Unraveling the dual role of bilirubin in neurological Diseases: A Comprehensive exploration of its neuroprotective and neurotoxic effects (2025) Brain Research | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2025.149472

Lee, Y. et al.: Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine-based combination chemoimmunotherapy (2023) Nature Communications | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40270-5

Leung, J.W. et al.: Expression of bacterial beta-glucuronidase in human bile: an in vitro study (2001) Gastrointestinal Endoscopy | https://doi.org/10.1067/mge.2001.117546

Lightner, D.A.: Bilirubin (2013) | ISBN: 9783709116371.

Loboda, A. et al.: HO-1/CO system in tumor growth, angiogenesis and metabolism – Targeting HO-1 as an anti-tumor therapy (2015) Vascular Pharmacology | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vph.2015.09.004

Nobles, C.L. et al.: A product of heme catabolism modulates bacterial function and survival (2013) PLoS Pathogens | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003507

Ramírez-Mejía, M.M. et al.: The Multifaceted Role of Bilirubin in Liver Disease: A Literature Review (2024) Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology | https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2024.00156

Ren, K. et al.: Prognostic and immunotherapeutic implications of bilirubin metabolism-associated genes in lung adenocarcinoma (2024) Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine | https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.18346

Ryter, S.W. et al.: Carbon monoxide and bilirubin: potential therapies for pulmonary/vascular injury and disease (2007) American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology | https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2006-0333TR

Yi, F. et al.: Bilirubin metabolism in relation to cancer (2025) Frontiers in Oncology | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1570288

You, J.J. et al.: The relationship between gut microbiota and neonatal pathologic jaundice: A pilot case-control study (2023) Frontiers in Microbiology | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1122172

Zhang, F. et al.: Neuroinflammation in Bilirubin Neurotoxicity (2023) Journal of integrative neuroscience | https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2201009